In early 2019, the White House directed NASA to put astronauts on the moon by 2024. That would require an enormous increase in the agency’s budget – and at a time when folks on Capitol Hill haven’t been favorable to more big-ticket items or more requests from the Donald Trump administration. Despite the apparent lack of funding, NASA on Wednesday named 18 astronauts – including Spokane’s Anne McClain – to its team of astronauts to fly its projected Artemis missions and has been moving forward on getting a real lunar landing vehicle built.

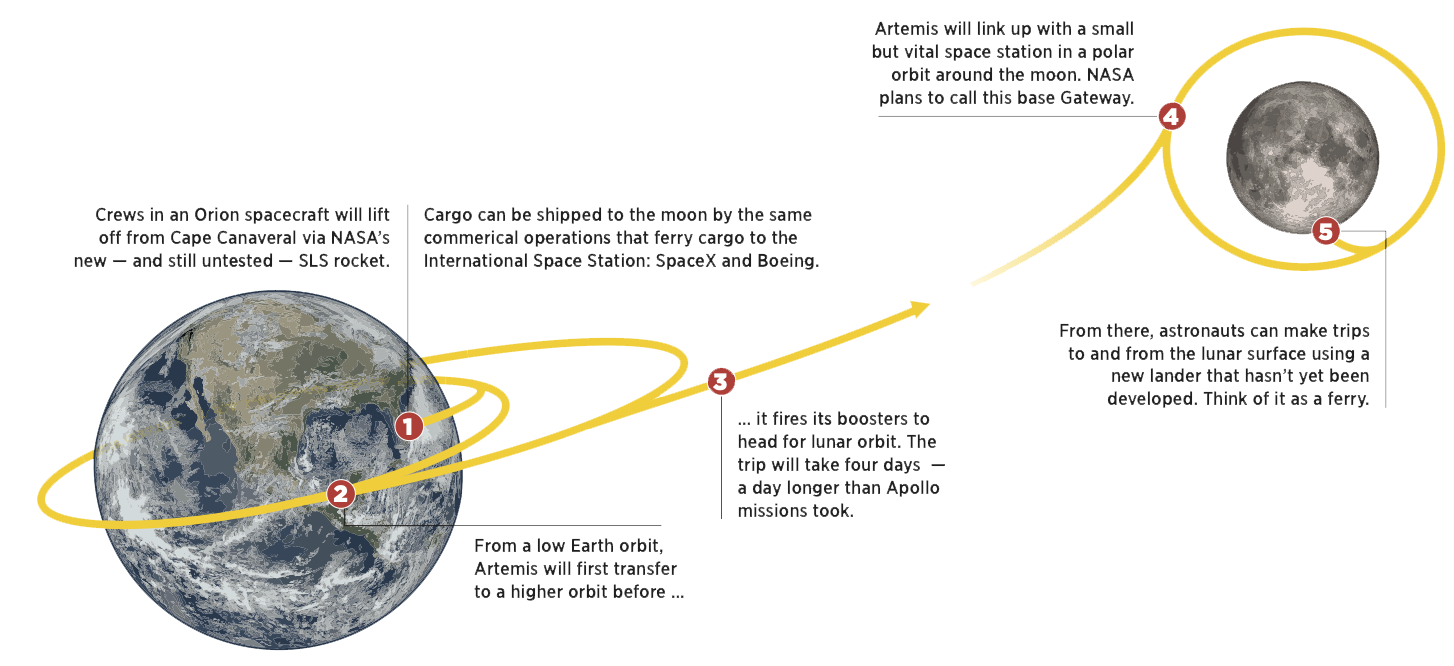

HOW THEY’LL GET THERE

An Artemis moon landing mission will differ from Apollo in a number of ways. One of the biggest: NASA intends to build a space station in lunar orbit and use that as a base from which it can launch multiple expeditions to the surface of the moon.

-

Crews in an Orion spacecraft will lift off from Cape Canaveral via NASA’s new – and still untested – SLS rocket. Cargo can be shipped to the moon by the same commercial operations that ferry cargo to the International Space Station: SpaceX and Boeing.

-

From a low Earth orbit, Artemis will first transfer to a higher orbit before ...

-

... it fires its boosters to head for lunar orbit. The trip will take four days – a day longer than Apollo missions took.

-

Artemis will link up with a small but vital space station in a polar orbit around the moon. NASA plans to call this base Gateway.

-

From there, astronauts can make trips to and from the lunar surface using a new lander that hasn’t yet been developed. Think of it as a ferry.

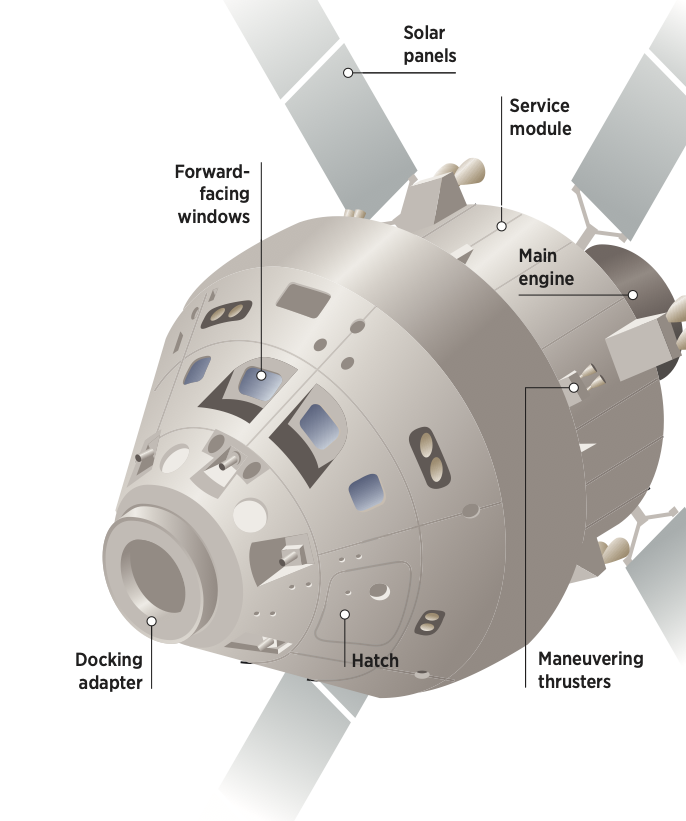

WHAT THEY’LL RIDE IN

It’s way too early to tell how accurate the artist’s rendering, at the top of this page, will be in depicting an Artemis lunar lander. Not only has it not yet been built, NASA is still studying proposals on how to design and build it.

On the other hand, the vehicle that will carry astronauts back and forth between Earth and lunar orbit – NASA’s new Orion spacecraft – has been under development by Lockheed Martin since 2004.

The service module – which will carry fuel and oxygen – will be built by German-based Airbus for the European Space Agency.

SIZE

16.5 feet in diameter, but with 50 percent more volume than an old Apollo capsule.

CREW

Two to six – probably four on longer missions.

REUSE

Designed to “splash down” in saltwater, yet NASA insists Orion will be reusable.

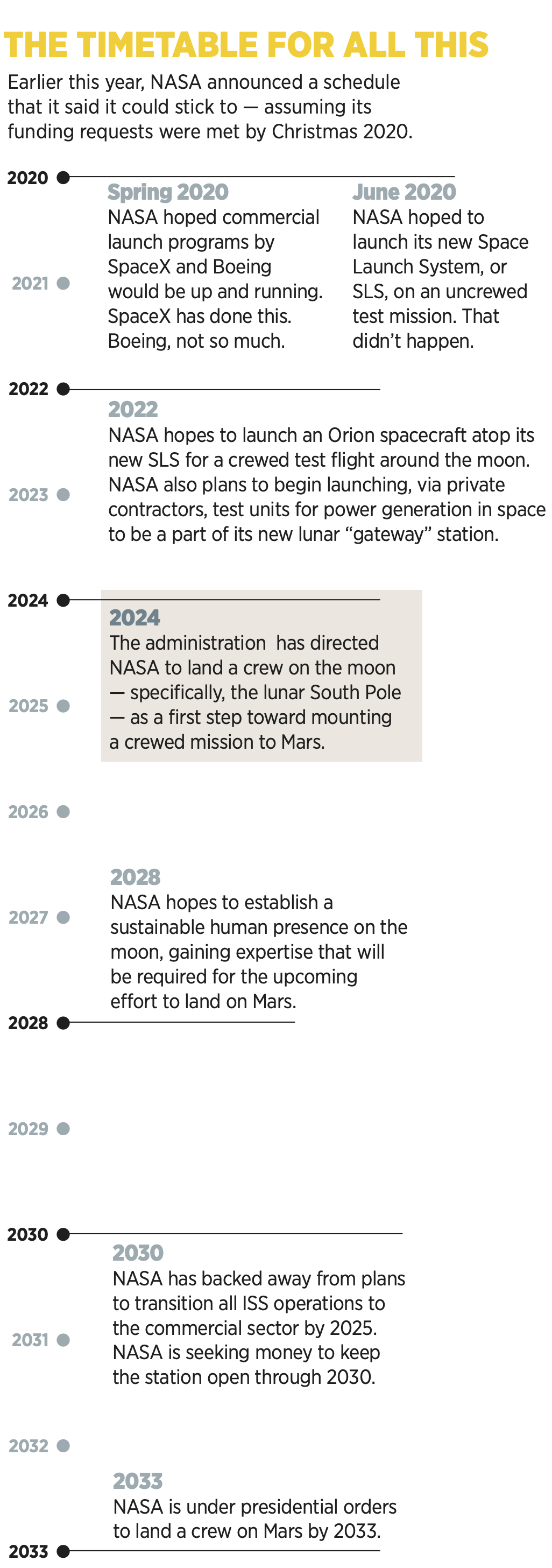

THE TIMETABLE FOR ALL THIS

Earlier this year, NASA announced a schedule that it said it could stick to – assuming its funding requests were met by Christmas 2020.

Spring 2020

NASA hoped commercial launch programs by SpaceX and Boeing would be up and running. SpaceX has done this. Boeing, not so much.

June 2020

NASA hoped to launch its new Space Launch System, or SLS, on an uncrewed test mission. That didn’t happen.

2022

NASA hopes to launch an Orion spacecraft atop its new SLS for a crewed test flight around the moon. NASA also plans to begin launching, via private contractors, test units for power generation in space to be a part of its new lunar “gateway” station.

2024

The administration has directed NASA to land a crew on the moon – specifically, the lunar South Pole – as a first step toward mounting a crewed mission to Mars.

2028

NASA hopes to establish a sustainable human presence on the moon, gaining expertise that will be required for the upcoming effort to land on Mars.

2030

NASA has backed away from plans to transition all ISS operations to the commercial sector by 2025. NASA is seeking money to keep the station open through 2030.

2033

NASA is under presidential orders to land a crew on Mars by 2033.

THE CATCH?

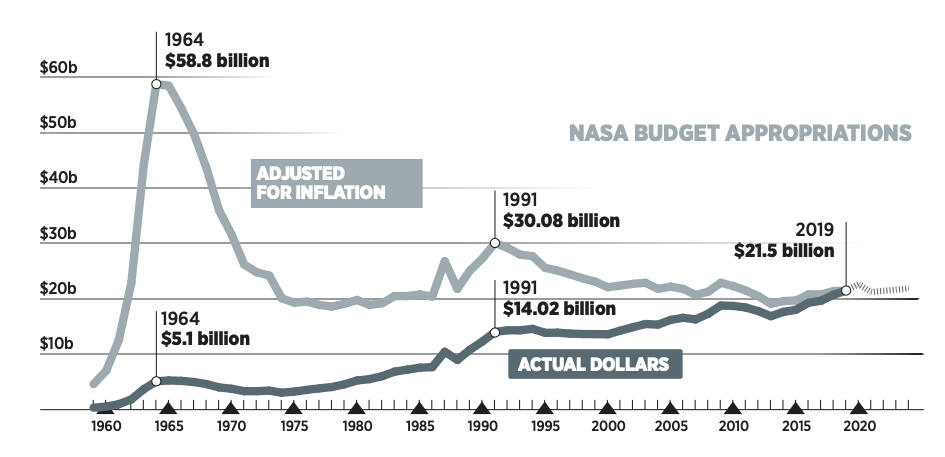

Exactly what you’d expect it to be: Money. Developing new technology is extremely expensive and Congress hasn’t climbed aboard just yet.

The Trump administration’s 2021 budget request sought a 12% increase in NASA’s budget from the previous year, for a total of $25.2 billion. Also, NASA officials have said NASA’s plans for Project Artemis would cost an additional $35 billion on top of what it already receives. So far, Congress has provided neither the 12% increase nor the additional funding.