‘I can’t tell you everything’: As investigation of Newport murder continues, new information emerges

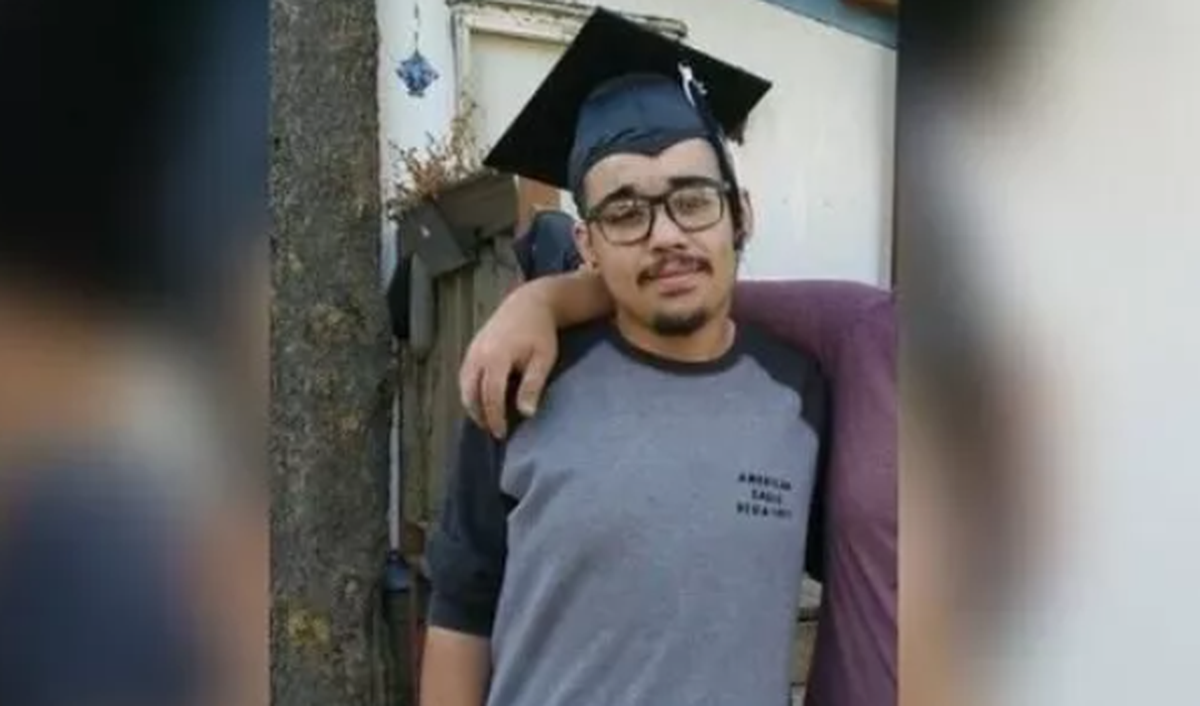

Jason Fox was killed on the outskirts of Newport. One of four suspects in his killing was sentenced Friday. (courtesy)

Pend Oreille County Sheriff Glenn Blakeslee is well aware that residents have been left to wonder why 19-year-old Jason Fox ended up in a shallow grave on Sept. 15, his hands bound behind his back, on the grounds of a riverfront wedding venue outside of Newport.

While the motive for Fox’s killing is a puzzle, four local men are jailed on charges of murder.

“The question is out about why he was killed,” Blakeslee said on a recent afternoon. “We have some information, but we want to be sure before we put any information out.”

So far, the investigation has uncovered a web of drugs, harassment and violence among a group of young adults.

Fox’s family has said they believe the killing was motivated by their son’s bisexuality and “flamboyance.”

Blakeslee said investigators “haven’t ruled in or out the hate crime” theory, but nothing in publicly available court documents suggests Fox’s sexuality was the reason he was killed.

Although those documents suggest drug use was prevalent among Fox and those suspected in his murder, they don’t definitively say whether drugs somehow led to the killing.

Blakeslee urged patience, saying the investigation is “very much still active” and that his department is working with Newport police, Idaho law enforcement, the Washington State Patrol, the FBI and “others I don’t want to mention for the time being.”

He also suggested they have found more than they have disclosed in the few court filings so far made public.

“I can’t tell you everything that I know,” Blakeslee said.

Connections

What Blakeslee, his fellow investigators and prosecutors have alleged is that Fox and the men accused of killing him had a tangled history.

Search warrants and police interviews outline their suspicions that Matthew Raddatz-Freeman, Riley Hillestad, Claude “C.L.” Merritt and Kevin Belding were involved in Fox’s killing at the Timber River Ranch Waterfront Weddings venue a few miles northwest of Newport in mid-September.

Fox’s mother, Pepper Fox, says she doesn’t know when or why Fox initially befriended Raddatz-Freeman, Hillestad, Merritt and Belding. But she believes he became involved with them sometime after moving out of his father’s home in Newport earlier this year.

For a time, Fox was couch surfing with hopes of going to college and becoming a nurse.

Then, about six months ago, he moved in with Raddatz-Freeman and his girlfriend, Amanda Pierson.

Fox then moved in with a relative, and Raddatz-Freeman and Pierson moved to the Timber River Ranch property at 22 Yergens Rd. Hillestad also took up residence at the property.

During the summer, tensions grew.

Fox told deputies in June that Raddatz-Freeman swung a pipe at his car during an argument. He also said Raddatz-Freeman “bullied him into giving Pierson money,” according to court documents.

In late July, Fox told authorities Hillestad and Raddatz-Freeman smashed his car windshield after he had taken a license plate off Hillestad’s car.

In a written statement in the police report, Fox said Hillestad had an assault rifle and was yelling “about how he wanted to shoot” him.

The ranch

The Timber River Ranch, as 22 Yergens Road has been known, sprawls across more than 50 acres along the slow-moving Pend Oreille River.

It’s such an idyllic spot that its owners, Ken and Shannon Sheckler, were able to charge upwards of $4,000 to couples searching for a secluded place to marry.

But the success of the Shecklers’ wedding-venue business began to fray over the past year and half, according to Aaron Jones, a lawyer representing Shannon.

First, Ken filed for divorce last year. Then COVID-19 arrived and “threw a wrench” into a business predicated on bringing people together, Jones said.

A judge eventually granted Shannon “full control” over the ranch and ordered Ken to leave the property.

When Shannon and her attorney arrived at Timber River Ranch on Sept. 13 to conduct an inventory of the shared property at stake in their divorce proceedings, they found things in disarray.

They also found a group of people they didn’t know living on the property, including in the ranch’s main house. Those people included Raddatz-Freeman, Pierson and others. They heard a baby crying, Jones said.

As they continued their survey of the property, they came to a tiny home located down a dirt road, closer to the river.

When Jones knocked on the door and announced himself, Hillestad came to the door, armed with “two pistols in his belt,” according to Jones.

During a brief conversation, Jones said, “Riley indicated he had the authority of Ken to run the place.”

As he tried to press Hillestad about what he meant and where a number of missing vehicles were, Jones described Hillestad’s answers as vague.

Two days after Jones and Shannon Sheckler toured the ranch and took inventory, Fox drove to the wooded property and ended up beaten to death and buried.

Ken Sheckler’s attorney, Joe Kuhlman, rejects the claim that Ken left the men in control of the property. Kuhlman described Ken Sheckler as “just another victim of these nefarious individuals.”

“With Mr. Sheckler not being allowed on the property by the dissolution action,” Kuhlman said, referring to the judge’s order, “there was certainly nothing to stop them from squatting on the property.”

In fact, Kuhlman said, a case against Hillestad and Raddatz-Freeman for wire fraud, theft and other charges is “already in the works.”

“They stole from him, and they left him nearly penniless,” Kuhlman said. “These are opportunists who took advantage of a man at his lowest point.”

The disappearance

The day after Shannon Sheckler and her attorney surveyed the property and encountered Hillestad and Raddatz-Freeman, investigators reported Fox made a drug deal with a woman who appeared to be dating Hillestad.

Fox didn’t have the money to buy meth from her, court documents say, so he gave her his Apple Watch to hold as “collateral” until he could pay her.

When Fox realized he’d been given salt instead of meth, a search warrant says, he sent the woman a Facebook message trying to get his watch back. Their last communication over Facebook is Fox’s unanswered “Hello?”

At the same time, search warrants say Fox was messaging someone else about buying drugs.

Later the same night, just before midnight, Fox had his last interaction on Facebook, when he exchanged messages with Merritt. Fox said he wanted to hang out with Merritt, but not Hillestad.

Merritt assured Fox that Hillestad wasn’t there, writing, “Bro, that’s why I’m at where I’m at because I don’t like that (expletive) around me.”

A few minutes before his last contact with Merritt, Fox texted his aunt’s boyfriend, saying he would be at 22 Yergens Rd. “in case something happens to me,” according to court documents.

The search

The next day, Fox’s aunt reported him missing.

The day after that, on the afternoon of Sept. 17, a Pend Oreille County sheriff’s deputy and a Newport police officer arrived at 22 Yergens Rd. in search of Fox after an emergency cellphone “ping” showed he’d been there just after midnight.

They found Hillestad, Raddatz-Freeman, Merritt and Pierson at the property. Each one told investigators something different about when they had last seen Fox.

Merritt said he hadn’t seen Fox in two weeks. Hillestad said he hadn’t seen Fox for a month.

Raddatz-Freeman said Fox “knew better than to come out there,” according to court documents, and had not been there for two months. Pierson said Fox had been on the property a week prior, adding he had to be “escorted” off the property.

On Sept. 22, Fox’s vehicle was found in Libby, Montana. Phone records indicated Raddatz-Freeman’s phone was in the same place after Fox’s disappearance.

Investigators returned to the ranch for another round of interviews.

The four men who are now charged in the case told varying versions of a similar story – that Fox had come out to the ranch in the early hours of Sept. 15 and gotten into an argument with Raddatz-Freeman. When it appeared that Raddatz-Freeman was about to assault Fox, they said, Merritt intervened. Fox then left in a silver car and the men followed him off the property to make sure he left.

Law enforcement later got consent from Shannon Sheckler to search the property. On Oct. 2, they found a pill bottle with Fox’s name on it along a trail leading to state land next to the ranch . Authorities then found black sunglasses broken with the lenses missing, court documents say.

In a clearing off the trail, investigators found two parked boats, one up on a trailer and one sitting on the ground. Dogs brought to aid the search alerted authorities to the grounded boat.

Beneath it, they found what appeared to be fresh gravel, with tire tracks leading toward it, court documents say.

Two days later, authorities brought a backhoe to the property and began digging beneath the boat. They found Fox’s body, his hands bound behind his back.

Conflicting stories

When authorities interviewed the four suspects and Pierson again more than a month later on Nov. 7, Hillestad showed up first, “wearing a ballistic vest, pepper spray, hand cuffs, knives, an AR-15 and a handgun,” according to court documents.

In his conversation with deputies, Hillestad talked “angerly (sic) under his breath about” Ken Scheckler “and said he should have killed him when he had had the chance,” according to court documents.

Hillestad also did what three of the four suspects would ultimately do in interviews with investigators that day: acknowledged that Fox had been killed at 22 Yergens Rd. in the early hours of Sept. 15, but denied doing so himself and cast blame on his fellow suspects.

Hillestad reportedly told deputies Merritt and Raddatz-Freeman had beaten Fox in a shop on the ranch property.

Merritt, however, blamed Hillestad and Raddatz-Freeman.

Raddatz-Freeman told investigators Merritt and Hillestad had beaten Fox nearly to death while Fox was seated in a chair before burying him, presumably alive.

All three also indicated Fox was buried on the property using a skid-steer, a small bulldozer. All denied their involvement in the shallow burial.

Belding was the outlier. He stuck to the story detectives deemed “fabricated,” according to court documents: Fox had driven his car off the ranch property.

The aftermath

Investigators have spent months piecing together what happened to Fox. They have searched the phones and electronic records of about a dozen people. They have interviewed many more.

All four men are charged with first-degree murder and jailed on bonds as high as $1 million.

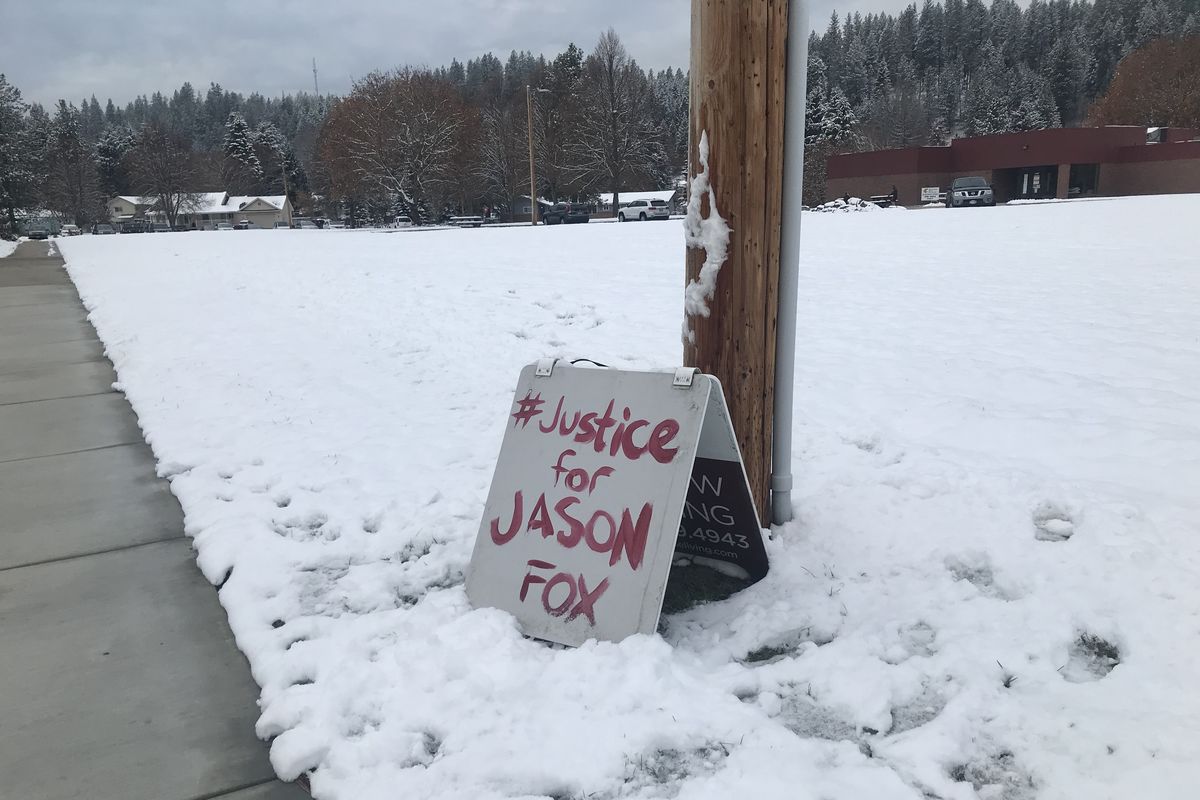

While those arrests ended a large share of the uncertainty surrounding Fox’s disappearance and discovery, uncertainty, animosity and questions remain.

Paul “P.J.” Hillestad, Riley Hillestad’s father, said the house in Newport where he has lived all his life has been hit with rocks and eggs.

“I’m very sorry for the Fox family, for their pain, but I lost a son too, like the others,” he told The Spokesman-Review. “I’m just asking to leave us alone and let the system work itself out. I’m tired of being harassed by people. The cops say stay low, but why do I have to bunker up?”

As soon as Pepper Fox learned her son had disappeared, she prepaid several months of rent at her residence on the West Side, booked a motel room in Newport and lined the walls with pictures of her son.

She’s approached everyone involved in the investigation, including the four arrested suspects and Fox’s drug dealer, demanding answers.

“There’s people who think I’m strong. I feel like I’ve lost my mind. I miss my baby so much. I think people are mistaking a gal that has nothing left to lose with someone who’s brave,” Pepper said. “I want to know the truth. I want justice. People here ask me for help now because they think I’m brave. I’m not. I’m a nobody that lost their kid.”

While Sheriff Blakeslee expressed sympathy for the Fox family, he also said all the back and forth about what may have happened and the rush to speculate on why Fox was killed “has actually been harmful to the case.”

That hasn’t stopped Pend Oreille County Prosecutor Dolly Hunt from pursuing a litany of charges against the accused murderers, even as Blakeslee and his deputies continue to investigate what happened on 22 Yergens Rd.

“I don’t have the full investigation,” Hunt said. “That hasn’t been provided to me. Law enforcement is still working on that.”

What Hunt is not pursuing, at least for now, are charges related to a hate crime.

And nowhere in court documents does Fox’s sexuality come up as a potential factor in his death.

Another thing missing from those documents, despite the first-degree murder charge, is an explanation of whether – and, if so, how – the murder was premeditated.

Hunt said premeditation isn’t a necessary element of such a crime and that it’s not the element she is charging it under.

Citing the ongoing investigation and the ethics of her office, she declined to say much more.

“We’re working the case like we’d work any other case,” she said. “There’s not a lot I can share with you.”

Correspondent Fred Willenbrock contributed reporting for this story.