John Blanchette: Dave Vaughn recalls bat boy duties for magical Spokane Indians team of 1970

He had broken his left arm in a mishap at church camp and was shackled with the standard wrist-to-elbow cast.

But Dave Vaughn also had a 15-year-old’s ingenuity and perseverance, a deep love for baseball – and the best summer job in America as incentive: batboy for his local pro team. So it was no surprise that within a matter of days he’d brainstormed a life hack with a glove borrowed from the club’s left-handed first baseman. Vaughn would catch a throw with his right hand, holster the mitt on his casted arm while deftly exchanging the ball to his now-bare right and then rifle it back – all so he could play pepper with the big boys of the 1970 Spokane Indians.

Which didn’t escape the watchful eye of Tommy Lasorda.

He’s now the oldest living Hall of Famer, but in 1970 Lasorda was the manager of the Dodgers’ Triple-A farm club in Spokane and polishing his persona as baseball’s master motivator – whether a team that would win its division by 26 games needed motivation or not.

So one day he gathered his players in the dugout and summoned Vaughn to his side.

“You’ve been watching this batboy here,” Lasorda preached. “I’m going to tell you what it takes to get to the major leagues. You’ve got to have a love for the game, you’ve got to find a way, you’ve got to have the desire. Look at this kid! He broke his arm! He’s out here playing! He’s not letting anything stop him!”

Players bit their lips and tugged their caps down low so Lasorda couldn’t see their eyes roll. The bat boy’s face matched the red script “Indians” across the front of his uniform.

“I was so embarrassed,” Vaughn recalled. “But I was proud, too.”

So Tommy Lasorda’s message reached somebody, anyway.

The Spokane Indians never took the field in 2020, sidelined by the coronavirus pandemic and Major League Baseball’s preoccupation with salvaging its own abridged season for the TV dollars. So there was never an opportunity to acknowledge the milestone anniversary of the franchise’s high point.

It’s been 50 years since the best minor league team in history played at the Fairgrounds ballyard.

OK, so this is not a unanimous verdict. In 1993, Baseball America magazine ranked the top minor league teams of the previous 50 years and put the 1970 Indians at No. 1. Just eight years later, however, the minor leagues’ umbrella organization tasked historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright to pick the 100 best of the century and they left that Spokane team off the list completely. This seemed an odd choice, in that at No. 38 they had the 1970 Hawaii Islanders, who were swept 4-0 by Spokane in the Pacific Coast League championship series.

And, no, Spokane’s 94 regular-season victories that year don’t stack up to the 137 by the 1934 Los Angeles Angels – No. 1 in the Weiss-Wright noodling.

But a great wine is judged out of the bottle, not by counting the grapes on the vine.

“What was amazing about that team was that so many of the impact players were 20, 21 years old – that was unusual at the Triple-A level,” said Vaughn, a retired Spokane high school counselor who coached baseball at Mead and, earlier, Whitworth. “A lot of the visiting players I remember were veterans at the end of their careers trying for one last shot.

“The other amazing thing was the kind of careers those guys went on to have.”

And that’s what set the ’70 Indians apart.

Twelve of them spent 10 or more seasons in the big leagues after their time in Spokane. Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes and Bill Russell – along with Ron Cey, who didn’t touch down in Spokane until 1971 – formed the starting infield that took the Dodgers to four World Series between 1973 and 1981. Knuckleballer Charlie Hough won 216 games in 22 seasons. Bill Buckner, Tom Paciorek and Doyle Alexander were All-Stars. The most prized among them and the PCL MVP in 1970, Bobby Valentine, had his star dimmed at age 23 when his spikes caught in the outfield fence as he tried to glove a home-run ball, shattering his right leg.

They hit .299 as a team during the regular season – 25 points higher than Hawaii – and outscored the Islanders 36-9 in the title series, in which the starting pitchers needed just one out of relief help in four games. Even when Valentine suffered a fractured cheekbone when hit with the first pitch of Game 4, replacement Marv Galliher banged out a home run, triple and two singles.

“The way they carried themselves was just different,” Vaughn said. “I was only five, six years younger than some of them, but I don’t know if I even had hair under my arms. It was an education in how to play – and a lot of other things.”

The contest was co-sponsored by the club and the old Spokane Chronicle: In a pithy essay of 30 words or less, make your case to be the Indians’ batboy for 1970, to be judged on “interest, clarity of thought and neatness.”

About 100 boys ages 10-17 took up their pens. Vaughn can’t remember his pitch, but one entry took the Hail Mary approach: “If I win, it would be the first thing I ever won.”

The winner turned out to be Mike Wilson, a ninth-grader at Green-acres Junior High. He was assigned the Spokane clubhouse.

Vaughn, a student at Ferris, got the visitors. Three other entrants got season tickets.

“I always think I got the better job,” Vaughn said. “I was always in and out of the Indians clubhouse, but I was around all these other players and managers, too. And there were some incredible characters – Don Zimmer, Chuck Tanner, Rocky Bridges. I heard so much – and some things your parents wouldn’t want you hearing.”

It wasn’t all fetching bats and rosin bags. He was a go-between delivering notes from players to female fans in the box seats (“though more often it was from the girls to the players”). Once, he inadvertently sparked a sobering conversation among the Tucson Toros, having brought to the clubhouse his copy of the latest Sports Illustrated featuring Tony Conigliaro on the cover. It had been Toros pitcher Jack Hamilton, with the Angels three years earlier, whose 95-mph fastball had hit Conigliaro in the face, changing the course of the Red Sox outfielder’s promising career – and haunting Hamilton to a degree for decades.

And Vaughn learned how to chew tobacco. Or, rather, how not to.

“Chico Vaughns played for Portland and he asked if I’d ever chewed,” Vaughn said. “It was leaf tobacco and he took some and wrapped it into a ball and tells me, ‘What you want to do is suck on it and get a mouthful of juice and then I’ll tell you what to do.’ ”

Which was swallow it.

“Immediately, the room is spinning,” he said. “I make it down the ramp to start the game and I collapse and the trainer and a couple players take me back up to the clubhouse. I spend the game on the training table – when I wasn’t throwing up. Chico’s saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry – we thought you knew.’ ” Any time now that I’m around that and smell it, it brings it all back.”

On the other side of the diamond, the brash Valentine would needle Vaughn about taking the batboy job for the money – $5 a game – and “all the free gum and sunflower seeds.” He’d play one-on-one pepper with Paciorek “and if I threw well and he got enough swings, he’d let me hit,” he said.

He might even eavesdrop on Lasorda breaking it to a veteran player that he’d be released at season’s end, and get an early lesson in that kind of baseball mortality.

And then there was the career he thought he’d ended.

Geoff Zahn was a 24-year-old left-hander juggling baseball with National Guard duty. As the stadium filled on 10-cent beer night, he was playing pepper down the right-field line with three or four players and the batboy.

“I was batting and Charlie Hough threw a knuckleball that I missed, and I ran to pick it up,” Vaughn remembered. “There was a big crowd, so I’m going to fire it back hard to the guys. And as I release the ball I see that Zahn isn’t looking. I yell and he looks up right in time for the ball to hit him in the side of the mouth.”

Zahn collapses, and blood immediately gushes from his mouth and ear. Medical personnel put him on a stretcher and take him to the hospital.

Vaughn, naturally, is hysterical.

“I’m crying in the Indians dugout and I’m saying, ‘I’ve ruined his career!’ over and over,” Vaughn said. “Bill Buckner puts his arm around me and says, ‘It’s not your fault.’ I’m praying the whole game in the other dugout, ‘Let him live.’ ”

Near the end of the game, Zahn returns from the hospital to the Indians dugout. When Vaughn approached him later to apologize, the pitcher beat him to the punch.

“My fault,” he insisted. “I wasn’t paying attention.”

And nothing was ruined – Zahn won 111 games in a 13-year major league career. He lived in Spokane for a few offseasons and turned up at a Whitworth practice once to counsel the pitchers – one of whom was none other than Dave Vaughn.

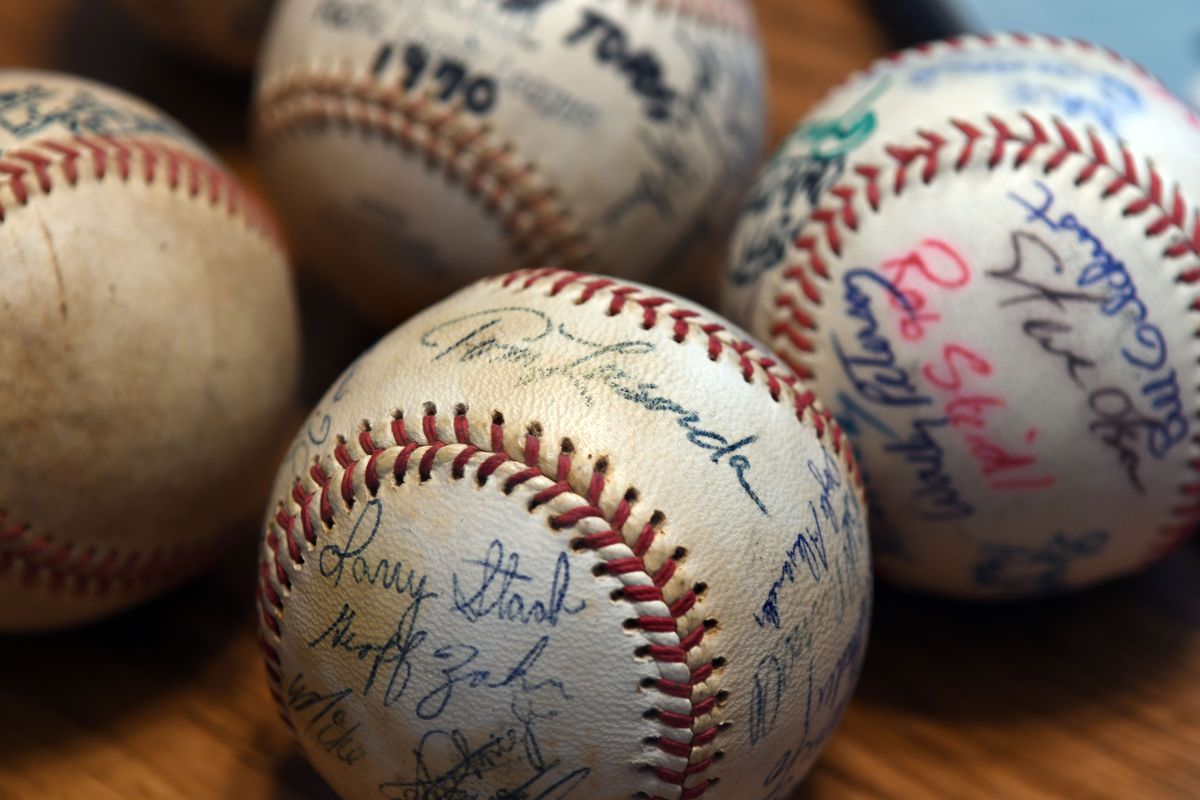

In the official team picture of the 1970 Spokane Indians – “Compliments of your Union Oil Dealer” – Dave Vaughn sits cross-legged at one end of the front row, next to Bobby Valentine and in front of a kneeling Bill Buckner and, yes, Geoff Zahn.

Just the batboy, but one of the boys.

“My buddies of that era – they would have paid anything to be in the position I was in,” Vaughn said. “What a great gift, to be able to walk into a locker room and have a uniform and just hang out with those guys.

“And not just any team, but that one.”