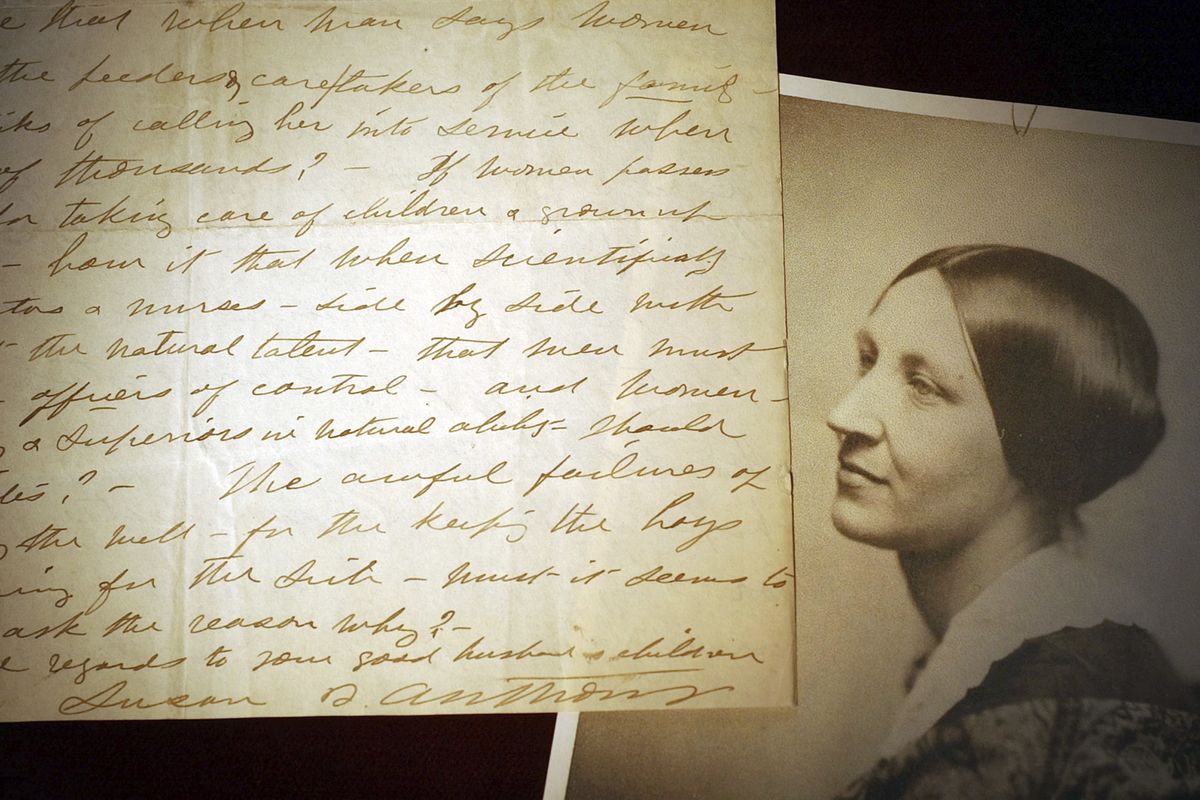

Verdict clear in Adams, Mass. birthplace: Susan B. Anthony would reject presidential pardon

ADAMS, Mass. – News that President Donald Trump would pardon an Adams native arrived as staff of the Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum swathed the famous activist’s childhood home in purple bunting.

They were setting out sunflowers, to symbolize the granting of municipal suffrage to Kansas women in 1887.

They were continuing efforts to erect a statute in Anthony’s honor, here on the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote in the U.S.

What they weren’t expecting was for Trump to issue a “full and complete pardon” of Anthony for her conviction on a charge of illegal voting in 1872.

When word reached Adams, the reaction to the pardon was clear: Trump can keep it.

“I feel certain that she would not have wanted to be pardoned,” said Carol Crossed, president of the museum’s board. “She wasn’t asking for the right to vote. She felt, as a citizen, she had an inalienable right. She would not admit guilt. She was a citizen with full rights.”

When Anthony’s attorney at the time went ahead and paid a fine that had been assessed, “she was very unhappy about that,” Crossed said.

James R. Loughman, the museum board’s vice president, emailed out a link to a news story about the pardon to allies Tuesday morning, without comment. The replies from those who keep the Anthony legacy alive agreed that, in this case, hold the forgiveness.

“The general consensus was, ‘I wonder if she’d even accept the pardon,’” Loughman said. “I don’t think that she would have accepted it.”

Even in her time, those prosecuting Anthony for daring to cast a vote in the 1872 presidential election in Rochester, N.Y., walked on eggshells.

“They didn’t want to turn her into a martyr,” Loughman said.

Anthony, he says, was disappointed to see the charges against her fizzle, legally.”She wanted to take her case to the Supreme Court,” Loughman said.

Anthony argued that the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, allowed women to vote. The amendment granted citizenship status and “equal protection of the laws” to all people born or naturalized in the U.S., including former slaves.

Instead, it was Elizabeth Minor, whose effort to exercise the voting franchise went to the nation’s highest court in 1875, in Minor v. Happersett. The court ruled against Minor, saying the Constitution did not grant her, as a citizen of Missouri, the right to vote, even if state law did provide voting rights.

“She made the very same arguments that Susan would have made,” said Loughman, a member of the museum board and the Adams Historical Society.

State Rep. John Barrett III, D-North Adams, who represents the town of Adams, said he sees irony in the fact that the president moved to celebrate a pioneer in securing the vote for women, even as his pick to run the U.S. Postal Service takes actions that could impair vote-by-mail efforts nationally.

“I think she wore her arrest like a badge of honor,” Barrett said of Anthony. “It’s very opportunistic. It’s time the president walked the walk instead of talking the talk.”

In addition to pardoning Anthony, the president declared August to be National Suffrage Month.

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The amendment passed in Congress in 1919 and was ratified Aug. 18, 1920.

Fourteen other women in Rochester also had voted like Anthony in 1872 and were arrested but never were taken to trial. Those women refused to pay fines and later were pardoned by President Ulysses S. Grant.