Hanford was a midwife to the atomic age

See Hanford, 10

In the beginning was a theory called fission.

While its details were complex, the basic idea was that if you could split a certain kind of uranium atom you could release energy. If you split lots of that uranium near another kind of uranium, you could create another element entirely – plutonium – that could release even more energy when it was split.

If you could get enough plutonium and make it release the energy all at once, you could make a bomb. A bigger bomb than anyone had ever seen.

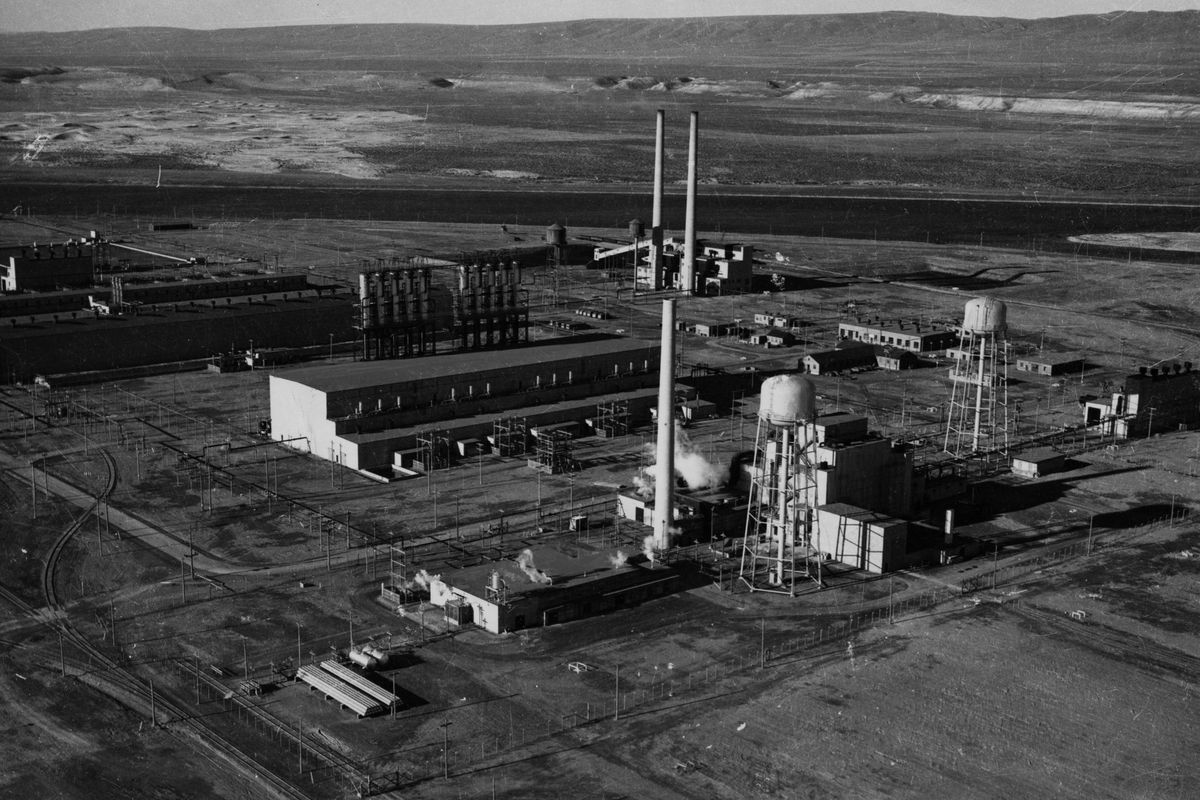

That theory was the beginning of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, which was the largest construction project ever attempted when built in the 1940s. Hanford helped prove the theory was correct and usher in what was dubbed “the atomic age.” The theory also created an unexpected legacy of big messes and bad decisions Washington and the nation are still struggling to correct.

Seventy-five years ago today, the theory partially obliterated the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

According to some, the theory brought a quicker end to World War II. Others argue the war would have ended without bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world’s second and third explosions of a nuclear fission weapon. But that argument needs some background.

‘This is it’

When the United States decided in 1942 to try turning the theory of nuclear fission into an actual bomb, it needed three things: An abundant supply of electrical power, an abundant supply of cold water and lots of empty space.

About one year after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Col. Franklin Matthias, the U.S. Army officer in charge of the search for such a place, flew over south-central Washington’s Rattlesnake Mountain and reportedly exclaimed, “This is it!”

Power was available from the recently completed Grand Coulee Dam, and water from the Columbia River.

The space wasn’t completely empty. There were farms and two small towns, Hanford and White Bluffs. Residents were ordered to leave, given 30 days and not much money. Native American tribes that had fished and hunted in the area for centuries were barred. A call went out around the country for construction workers.

At its peak construction, more than 50,000 workers were on the job at what was then called the Hanford Engineer Works. Only a handful knew what they were making. The vast majority weren’t told and followed orders not to ask. They were happy making the high wartime wages.

They built some 544 buildings, but one of the biggest and most complicated was the B reactor, which helped make the plutonium bomb theory a reality.

Scientists had shown in a University of Chicago laboratory, and later at another secret site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, that a chain reaction of particles from an unstable version, or isotope, of uranium, U-235, could collide with a stable isotope of the element, U-238, and turn it into plutonium. But they only generated tiny amounts of plutonium, and the Manhattan Project, as the effort to build the bomb was called, needed a large enough facility where many such reactions from many rods of uranium could be kept close together to make a larger supply of plutonium.

That was the B reactor, which could hold some 2,000 uranium rods in close proximity within a 36-foot cube of graphite.

All that uranium in close proximity creates large amounts of heat, which was cooled with water from the Columbia.

After about 100 days in the cube, the rods were ejected into a large pool of water, cooled further for about 90 days, then shipped to the T Plant, another massive building on the 568-square-mile site, to remove the plutonium. The water, contaminated with radioactive elements, was primarily stored in tanks. Some of those tanks with their radioactive waste remain on the Hanford site.

The plutonium came out in flecks that were compressed into “buttons.” The buttons were delivered by courier to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where more scientists were working on bomb designs.

‘Destroyer of worlds’

American scientists had two designs for an atomic bomb. They tested one, with Hanford plutonium, on July 16, 1945, in the New Mexico desert, in an operation called Trinity.

By then, Germany had surrendered and the United States and most of its allies were battling Japan in the Pacific. U.S. military leaders were preparing for a long and costly invasion of the island nation, projecting millions of casualties among combatants and civilians. President Harry Truman, who was meeting with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin later that month, wanted to know if the bomb, known as “the Gadget,” would work.

The scientists had a tower about 100 feet tall built in the Alamogordo desert to drop Gadget, which was an implosion bomb. The plutonium was contained in a sphere about the size of a softball, surrounded by 32 explosions that would push the plutonium inward to the size of a tennis ball, when it would release its energy outwards.

Or so the theory went. To make it work, the device needed a triggering device to set off all explosives in less than a millionth of a second of each other. Blasting caps wouldn’t work so precisely, but physicist Lawrence Johnston came up with an electric detonator that sent a high voltage charge to each explosive device.

The detonator worked and Gadget created the first atomic blast, illuminating the early morning desert with a blinding flash, destroying the tower and turning the sand beneath it to glass.

Seeing the power, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the bomb was assembled, said later that a quote from Hindu scripture ran through his head: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Gadget had an explosive force of about 20,000 tons of TNT, and the blast was felt throughout the state. Because the project was secret, people were told an ammunition storage bunker had exploded.

At a July 26, 1945, meeting in Potsdam, Germany, Allied leaders called for Japan to surrender unconditionally or face “prompt and utter destruction,” although they didn’t describe the weapon that would do that.

Asked about the Allies’ demand, the Japanese prime minister in Tokyo said he wouldn’t comment and used the word mokusatsu, which can be translated two ways: either treating with silent contempt or remaining silent for the time being. When the comment was reported to U.S. officials, the word was translated to say the government was rejecting the ultimatum with contempt. When the translation was later declassified, linguistics pointed out the prime minister might merely have been giving the Japanese equivalent of an American politician’s “no comment” and dubbed it the “The world’s most tragic mistranslation.”

While the divided Japanese government debated whether to accept surrender terms, the United States continued with plans for the invasion of the Japanese islands. The War Department projected more than a year of city-by-city and possibly block-by-block fighting, with civilians taking up arms. Officials began telling troops returning from Europe they were being sent to the Pacific, and caskets were stockpiled on Pacific islands for the expected casualties.

Little Boy, Fat Man

The United States had enough nuclear material for two bombs with two different designs. Little Boy, as it was eventually dubbed, used enriched uranium from another part of the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge. Fat Man was a plutonium bomb like Gadget, with material from Hanford.

The only way to deliver such a weapon in 1945 was to drop it from a plane. As part of the Manhattan Project, the Army created a special group of B-29 pilots, air crews and ground crews, the 509th Composite Group. The were altered to carry one large bomb, had some other armor and weight removed, and were dubbed “Silverplate” because of those and other special features.

The crews were handpicked, trained first in the United States and then sent to Tinian, a small island in the Pacific about 1,500 miles south of Tokyo. While the other bomber groups on the island took part in incendiary raids on Japanese cities, the 509th only practiced for a secret mission the crews knew little about. They spent their flying time over islands at altitudes approaching 30,000 feet and practiced dropping one bomb before returning to Tinian.

Parts for both bombs had been shipped separately to Tinian, arriving by sea or air for months, with final assembly taking place by scientists on the island. Among the limited number of high-ranking Army officials told about the project, some doubted it would work.

On Aug. 4, bomber crews were briefed on a three-plane mission that would take them over one of three Japanese cities in the next three days, depending on weather. They would drop one bomb. It was supposed to be practice – but not like any they’d ever done. They were shown pictures of the Trinity explosion.

Late the next evening, the crews were given the target of Hiroshima. One of the Silverplate B-29s named the Enola Gay was pulled over to a bomb-loading pit, and Little Boy, which the crews also called “the Gimmick,” was transferred to the bomb bay. Two other B-29s, Great Artiste and Necessary Evil, accompanied the Enola Gay, the former to drop instruments to measure the blast and the latter to photograph it.

About six hours after takeoff, the specially adapted bomb bay doors of the Enola Gay opened about eight miles above Hiroshima and Little Boy dropped. A minute later, it exploded.

“It seemed like the Earth just opened up and started to send a cloud. That which was down on the ground became nothing,” Ray Gallagher, the flight engineer on Great Artiste, told an interviewer in 1988 for a taped recollection of the flight for the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

Johnston, the physicist who had designed the plutonium bomb detonator and watched the Trinity explosion, was also on that B-29 with instruments designed to estimate the power of Little Boy through shock waves. In a 1995 interview with The Spokesman-Review, Johnston, then a retired physics professor at the University of Idaho, said a shock wave hit the plane like the bang of a 2-by-4 on the metal skin.

He and other scientists on the plane took turns looking out the window at the scene below.

“It was just so completely blown away,” he recalled.

The three planes returned to Tinian. Johnston said the scientists expected the Japanese to surrender after the Hiroshima bombing. They listened to Radio Tokyo, but there was no word of Hiroshima.

Meanwhile, back in the U.S.

In the United States, Hiroshima was top of the front page news.

“KING OF TERROR DROPS ON JAPS, GREATEST DEATH FORCE NOW REALITY,” the Spokane Chronicle’s Aug. 6 edition screamed in giant type.

“ATOMIC BOMB, MADE AT HANFORD, PRODUCT OF COSTLY GAMBLE,” The Spokesman-Review’s banner blared the next morning. “$2,000,000,000 Weapon Is Likely to Shorten War; Already Hits Japan.”

That banner wasn’t strictly true, because the Hiroshima bomb hadn’t been made at Hanford, although the paper carried a long story about the Trinity test in July in its effort to explain what an atomic bomb was.

The newspaper’s editorial page opined the secret of Hanford was “long and well-kept.” Although millions knew that something “strange and fantastic” was being made there, not more than a dozen knew what was actually happening.

Although the paper chided the government as being a bit “too hush-hush” and suggested it could have called Hanford a generic “munitions plant,” the editorial complimented the people who kept the secret.

“The fact the secret has been kept so many years is a tribute to the cooperation of workers on the job, residents of the surrounding area, and the news writers of both the printed word and the radio who generally followed the request of the army in keeping discussion of the project at a minimum and in releasing such details as clearly did not affect the public security,” it said.

A second strike

On Aug. 9, three bombers from the 509th launched again. This time Fat Man, the plutonium bomb with the detonator Johnston devised, was in the bay of Bock’s Car. Gallagher was the flight engineer on that bomber; Johnston was again in Great Artiste.

The primary target was Kokura, an industrial city on the island of Kyushu. But the weather over Kokura was bad, and the crew had instructions to see their target before dropping the bomb. Maj. Charles Sweeney, the aircraft commander, circled the city several times hoping for a break in the clouds until, with fuel running low, Bock’s Car headed north to Nagasaki, the secondary target, about an hour away.

As they approached Nagasaki, the weather was cloudy and Sweeney said they only had enough fuel to make a single pass over the city. They had to decide whether to drop the bomb even if they couldn’t see the target and rely on radar for location, or return without dropping the bomb on the city, perhaps dropping it in the ocean because they weren’t sure they should land with a live bomb.

Over Nagasaki, the clouds cleared briefly, the bombardier sited his target and dropped Fat Man. In Great Artiste, Johnston again was monitoring the blast. He was the only person to witness all of the first three atomic explosions.

That plane also dropped a series of letters to a Japanese physicist who had studied in the United States. Physicists from the Atomic Bomb Command headquarters urged him to use his influence with the Japanese military high command to end the war.

“As scientists, we deplore the use to which a beautiful discovery has been put,” the unsigned letter said, “but we can assure that unless Japan surrenders at once, this rain of atomic bombs will increase many fold in fury.”

The military found the letter, but didn’t deliver it to the physicist for about a month.

Damage estimates

Bock’s Car was so low on fuel it had to land at Iwo Jima to refuel before returning to Tinian, where scientists again expected word of Japanese surrender. None came as Army Air Force and Navy observation planes surveyed the damage of both cities.

The Little Boy blast had an estimated power of 17,000 tons of TNT, and killed an estimated 60,000 to 70,000 people immediately, with tens of thousands dying in the coming days, weeks and months from aftereffects like burns and radiation poisoning.

The more efficient Fat Man had an estimated power of 20,000 tons of TNT, but the bomb exploded about two miles away from its intended target, in a valley which absorbed and shielded some of the effects. Estimates of the immediate dead vary widely, from about 28,000 to 75,000. Another 35,000 to 40,000 people died later, and an estimated 60,000 were injured.

The front page of The Spokesman-Review on Aug. 9 carried an 11-paragraph report of the Nagasaki bombing, but the top headline was about the Soviet Union declaring war on Japan.

The next day’s front page didn’t mention Nagasaki specifically, instead carrying the warning from the president about continued bomb use: “JAP SURRENDER ONLY WAY TO STOP CONTINUED ATOM BOMBING – TRUMAN.”

The accompanying story quoted Truman as saying the United States used the bomb “in order to shorten the war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousand of young Americans. We will continue to use it until we completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.”

The front page also carried an editorial cartoon of a frightened world peering from behind a wooden fence at an atom that had broken its chain – although the atom looked a bit like Reddy Kilowatt, the cartoon mascot for electric energy. Another story offered an account of four congressmen making an impromptu visit to Hanford after touring the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, and receiving a tour of buildings, which they only saw from the outside and at a distance.

On Aug. 10, the Japanese government sent a telegram offering to surrender. But it did not seem to be the unconditional surrender Allied leaders had agreed to seek at Potsdam, because it included a provision that Emperor Hirohito would remain as the head of the government.

As negotiations continued, the Soviet army began sweeping through Japanese-held Manchuria.

On Tinian, scientists began assembling another plutonium implosion bomb like Fat Boy, and Gen. Leslie Groves asked the War Department for other targets. President Harry Truman nixed any plans for dropping another atomic bomb, and on Aug. 14, the Army Air Force mounted a raid of multiple cities in Japan involving more than 1,000 bombers launched from Tinian, Iwo Jima and Saipan.

By the time the last of those planes returned to their island bases, the Japanese surrender was final. Emperor Hirohito had taken the unprecedented step of going on the radio to tell his people they had done their best, but circumstances had turned against them.

“Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives,” he said. Continuing the war would lead to the obliteration of the nation and “the total annihilation of human civilization.”

Although the surrender document wouldn’t be signed until Sept. 2, on the deck of the USS Missouri, Americans poured into the streets to celebrate Victory over Japan, or V-J Day.

‘In a place to save a lot of lives’

Whether the atomic bombs ended the war, as soldiers, scientists, Allied leaders – and even Hirohito – said then and for decades after remains a debate three-fourths of a century later.

In his memoir, Truman wrote that military leaders had told him an invasion of Japan, which was planned for November, could cost a half-million American lives. The actual military estimates were lower than that, but regardless of the number, Truman said after the war that if he didn’t use the bombs and American troops died in an invasion he would have suffered the nation’s wrath.

Johnston, who witnessed all three Manhattan Project explosions, thought it did hasten the war’s end. In the interview 50 years later, he noted the death and destruction from conventional warfare was horrendous, too. He had no regrets about his part in creating the bombs.

“I’m thankful God put me in a place where I could save a lot of lives,” he said.

Sweeney, the pilot of Great Artiste on the Hiroshima flight and Bock’s Car on the Nagasaki flight, went on to become a major gen- eral in the Air Force and later the Civil Defense director of Boston. He said later that people need to remember the circumstances of August 1945, when the world had been at war for almost six years and the United States for going on four years.

“We were sick and tired of war,” he said in a 1962 radio interview now part of the Voices of the Manhattan Project. “Mothers and wives wanted the war to end, as did all the men in the jungles and all the men who had been overseas in the Pacific for three years.”

But some researchers contend that while Hiroshima and Nagasaki created massive casualties, they wouldn’t have been decisive. Scores of other Japanese cities, including Tokyo, had been decimated by conventional bombing in the summer of 1945, and some produced more death and destruction than the two atomic bombings.

The decisive factor, author Ward Wilson argued in his book “Five Myths of Nuclear Weapons,” was actually the Soviets declaring war on Aug. 9, which meant another major power – which previously had honored a non-aggression pact with Japan – attacking from another direction. Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave Japanese leaders an acceptable explanation for ending the war, but was not the cause, he argued.

Others say it’s possible the choice wasn’t between an invasion and dropping the atomic bombs.

The American military knew the Japanese government was talking about a surrender after Potsdam but wanted to be sure Hirohito was not tried as a war criminal. The American public had been promised an unconditional surrender, and that was a condition. Japan did surrender unconditionally on Aug. 15, but Hirohito wasn’t removed from his position as emperor.

Although the United States occupied and oversaw the restoration of the Japanese economy and the restructuring of its government for seven years after the war, Hirohito remained the emperor until his death in 1989, and was succeeded by his son and, in 2019, his grandson.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were rebuilt, although they retain some relics of the bombings as remembrances for the world of the effects of atomic weapons. The United States couldn’t keep the secret of the atomic bomb and soon was involved in a Cold War with its former Soviet ally that included a proliferation of nuclear weapons to keep the peace under a doctrine of “Mutual Assured Destruction.”

Hanford continued to make plutonium and other elements for the nation’s nuclear weaponry, with the radioactive waste they generate, until 1990. Some of the tanks of nuclear waste have leaked, and efforts to remove the toxic substances have bogged down over technology and costs. The state and the federal government have waged a legal war that has lasted far longer than World War II.