Sleepy Floyd on the game that almost ended Michael Jordan’s career: ‘You didn’t know the significance of the injury’

Sleepy Floyd doesn’t remember much about the specific moment Michael Jordan broke his foot, just that, all of a sudden, the Golden State Warriors had a better chance of beating the Chicago Bulls that October night in 1985.

“A lot of that game I can’t recollect, other than the fact that I remember him injuring himself,” Floyd, 60, said in a phone interview this week. “It didn’t change anything that we did on the court, but obviously it made the game against the Bulls a lot less challenging once he went out.

“You didn’t know if he was returning to the game. You didn’t know the significance of the injury.”

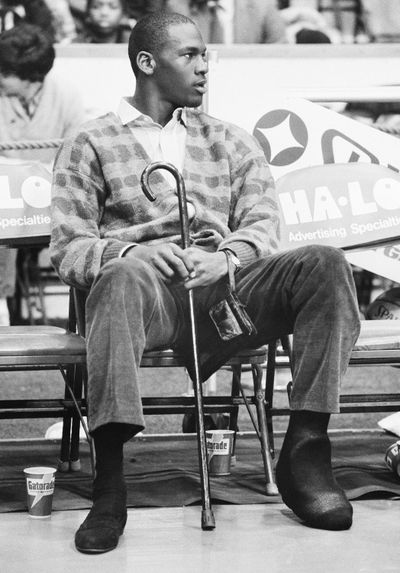

In only his second season, a 22-year-old Jordan had already established himself as one of the dominant players in the NBA. Despite Jordan playing only 18 minutes, the Warriors didn’t win the game in question, a 111-105 loss at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum on Oct. 29. When he landed awkwardly during the second quarter, Jordan suffered a fractured bone in his left foot that sidelined him for six weeks, and nearly threatened his career.

That injury was a key point in the second episode of “The Last Dance,” ESPN’s 10-part series that focuses on Jordan and the 1997-98 Bulls. After airing the first two episodes last Sunday, the network will roll out the final eight over the next four weeks, including Sunday at 6 p.m.

But in watching the first two episodes, which traced the start of Jordan’s career, Floyd was reminded of growing up with Jordan in North Carolina, where they, along with James Worthy, would often play against each other as some of the top players in the state.

“His athleticism was second to none,” Floyd said. “Coupled with his ball-handling skills, his passing skills and his knowledge of the game, it allowed him to become what he became.”

Three years older than Jordan, Floyd grew up in Gastonia, a city of more than 70,000 roughly 20 miles West of Charlotte. Jordan was raised on the East Coast in Wilmington, but they would often meet in youth tournaments.

Floyd played at Georgetown while Jordan and Worthy attended North Carolina. In 1982, they met again in the national championship game. Thanks to Jordan’s go-ahead jumper with 15 seconds left, the Tar Heels beat the Hoyas 63-62. The moment is often cited as the start of Jordan’s legacy.

“He made that final shot against us in the national championship game,” Floyd said. “So his game evolved, he got better. In the episode, he talked about always being driven to get better. You can see him getting better from year to year.”

But, as the documentary detailed, Jordan’s G.O.A.T.-status career was threatened in the fourth game of his second NBA season. When doctors advised there was a 10% chance Jordan could suffer a career-ending reinjury, Bulls ownership wanted to shut down Jordan for the remainder of the season.

“When I heard it was cracked, that really hurt me,” Jordan told reporters then. “What do I do from here? Six weeks of nothing? All I could think of was I would lay up, watch TV and do nothing.”

Meanwhile, Jordan returned to the University of North Carolina, where he participated in on-court drills without informing the Bulls. With rumors that the Bulls planned to tank in order to improve their draft positioning, Jordan returned and led Chicago to the playoffs. In the first round against the Boston Celtics, Jordan set the NBA playoff record with 63 points, leading to Larry Bird’s famous declaration that he was “God disguised as Michael Jordan.”

According to Floyd, Jordan was far more athletic than his peers when he came into the league as the third overall pick in the 1984 draft. That allowed the Bulls to play an up-tempo style, similar to Magic Johnson’s “Showtime” Lakers.

Floyd’s Warriors played at a slower pace, like the Celtics. So when Golden State matched up with a Chicago team that would push the speed of the game, Floyd looked forward to it.

“They played at a faster pace that suited my game a lot better than, say, a half-court game,” said Floyd, who played six seasons with the Warriors. “So, I always looked forward to playing against the Bulls or the Lakers or some of the teams that played up-tempo style, where it was more of a wide-open game and you played a lot on instincts.”

In front of a roaring Oakland crowd, Floyd scored a game-high 32 points the night Jordan suffered his foot injury, accounting for all four of the Warriors’ made 3-pointers in the game. Over his 13-year NBA career, Floyd made 518 3-pointers, about 40 a season, but believes he would have been more effective in today’s game that encourages taking shots from beyond the arc.

Meanwhile, greats like Jordan transcend style of play, something Floyd tries to explain to those too young to remember Jordan’s prime years.

“Not that it was better, but it was just a lot more of a physical game at that time,” Floyd said. “Being able to dominate that kind of style of play is hard for them to get an understanding of what that really means until they see highlights or documentaries.”