Book review: ‘Temporary’ puts a whole new spin on millennial woe

“If one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours,” Thoreau writes in “Walden.”

Under quarantine, Thoreau’s words seem naive. There is no advancement, much less confidence. All we know now are stasis and uncertainty. COVID-19 is a tidal wave to the modest sandcastle of millennial success: People who were just beginning to assemble their personal and professional lives into some semblance of livability are now trapped in an existential limbo.

Many are without health insurance or income. Many are “essential workers” risking serious illness to keep buses running and grocery stores open. The once-bleak economic situation of millennials forced to string multiple jobs together has become even bleaker in the economic collapse caused by the pandemic. Everything – work, health, safety – has come to feel temporary.

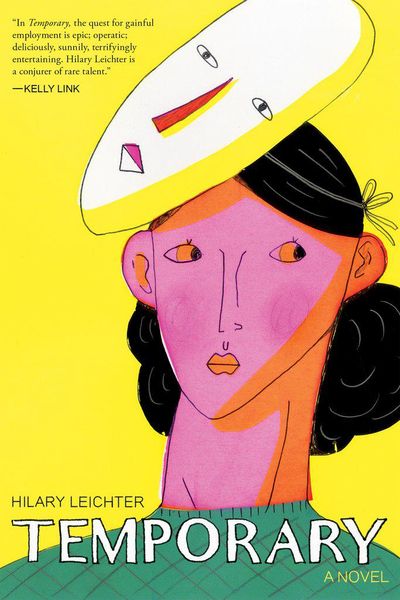

Enter into this global cataclysm Hilary Leichter’s “Temporary,” a refreshingly whimsical debut that explores the agonies of millennial life under late capitalism with the kind of surrealist humor that will offer anxious minds a reprieve from our calamitous news cycle. Leichter’s nameless narrator is a temp given absurd assignments, including stints as a pirate, an assassin’s assistant and a CEO (whose incorporeal form she later wears in a necklace around her neck).

Being a temp is a tradition that runs in the temp’s family: “We work,” her mother, who has filled in for skyscrapers, the mayor of New York City and her own mother, tells the temp, “But then we leave.” And even though the temp’s contact at the temp agency – the smarmy, all-business Farren, whom Leichter draws with the excessive snark such a character deserves – speaks of the goal of “permanence,” the temp seems to know that she’s doomed to a life of miserable temporariness.

The novel is punctuated by a series of Genesis-like tracts describing the life of the “First Temporary,” whom the gods created so they could “take a break.” The idea that temping has existed since time immemorial – and that our world is obsessed with streamlining, productivity and corporate bureaucracy on a depressingly metaphysical level – is fitting for a book about the quashing of free will under capitalism. Leichter smartly uses fantastical ideas (some of the best being a witch whose hair “shines like a wave of charitable donations” and a haunted house whose doors must be opened and closed at odd intervals) to communicate the drudgery of professional impermanence.

Leichter’s dry wit is masterful, but her novel suffers from the occasional tonal inconsistency. On the pirate ship, the temp is sexually assaulted: “He isn’t the first man to miscalculate what a woman would or wouldn’t do … with his hands under my skirt under the sails under the sky.” Similarly, the temp wonders about learning the assassin’s trade herself, making a hilarious pro/con list: “Under the pro column: Learn the new skill of murdering. Under the con column: Whoops, now you’ve murdered.” The levity of the moment feels coarse when her friend’s throat is slit seven pages later.

Still, as a book about the brutality of the work world, “Temporary” is a great success. Leichter has managed to blend the oddball and existential into a tale of millennial woe that’s dreadful and hilarious.