Washington’s 2020 presidential election starts in January and ends in December

In the United States, political parties use two different systems to select their presidential nominees, primaries and caucuses. Most states use one or the other – the most familiar are probably the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary.

Washington has used a hodgepodge of the two systems since voters passed an initiative creating a presidential primary 28 years ago. But Democrats stuck with the caucuses because of national rules, and Republicans choose their delegates through a combination of the two systems.

In 2020, for the first time in state history, Washington voters of both major parties cast ballots in a presidential primary to help select the two parties’ nominees.

But the parties won’t abandon the caucus system entirely. The delegates to national conventions, where those candidates are nominated, will come through a process that starts with caucuses at the precinct, or neighborhood voting district, or legislative district level.

Sound confusing? It is, but only slightly more so than presidential elections every four years since 1992, when the first presidential primary system required by an initiative was held, even though the two parties were free to ignore those results in favor of the caucus system.

In some years, voters could choose a Republican, Democrat or independent ticket. In others, it was strictly a partisan choice and voters, who in Washington don’t register by party, had to say that for the presidential primary they considered themselves a member of the same party as the candidate they selected. The law set the primary in late May, after the nominations are usually decided, but in some years it was moved to March to attract more candidates and national media attention.

In two election cycles, 2004 and 2012, the presidential primary was canceled to save money.

To give the presidential primary more weight, the Legislature passed a law in 2019 that tried to address complaints that the primary was too late to matter and at $10 million for the statewide vote, not worth the money for something the parties could ignore. The election will be held on the second Tuesday in March – March 10 – a week after the 15-state Super Tuesday event and the same day as primaries in Idaho, Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio, as well as caucuses in Hawaii and North Dakota.

The list of candidates on the Washington ballots will be finalized in early January and sent to voters in late February before the winnowing of the first caucuses and primaries, so state voters should have a large selection of candidates, even if some have suspended their campaigns. They can be marked and sent back any time before 8 p.m. March 10.

The Democratic and Republican parties will use the results of the primary to apportion delegates. Those delegates will go on to help select each party’s nominees at national conventions next summer.

In exchange for the Democrats’ participation in the primary system, the state had to limit the balloting to people who will declare a party preference and not offer voters an independent or unaffiliated ballot. In past elections when that was done, some Washington residents refused to declare a party and wouldn’t vote.

The parties have different formulas for determining how many delegates each state has and how they will be awarded. For the Democratic nomination, Washington has 107 delegates, with 89 awarded to candidates based on primary results and 25 automatic delegates – top-ranking elected officials sometimes called super delegates – who can support whomever they want.

The 89 “pledged” delegates are divided further, with 58 split among the state’s 10 congressional delegations based on population, and another 19 chosen statewide and 12 designated party leaders to be awarded based on statewide results. To qualify for delegates, a candidate must get at least 15% of the primary vote in a congressional district or state, but in some districts there may not be enough delegates for every candidate above 15%.

If no one gets 15% – mathematically possible if there are many candidates running for the nomination – there’s an even more complicated formula for awarding delegates at the top of the heap.

For the Republican nomination, Washington will have 44 delegates. A candidate will have to get at least 20% of the statewide primary vote to get a share of those delegates, and if any candidate gets more than 50%, he or she will get all of them.

People interested in becoming a delegate to a national convention will have to do considerably more than mark their presidential primary ballot.

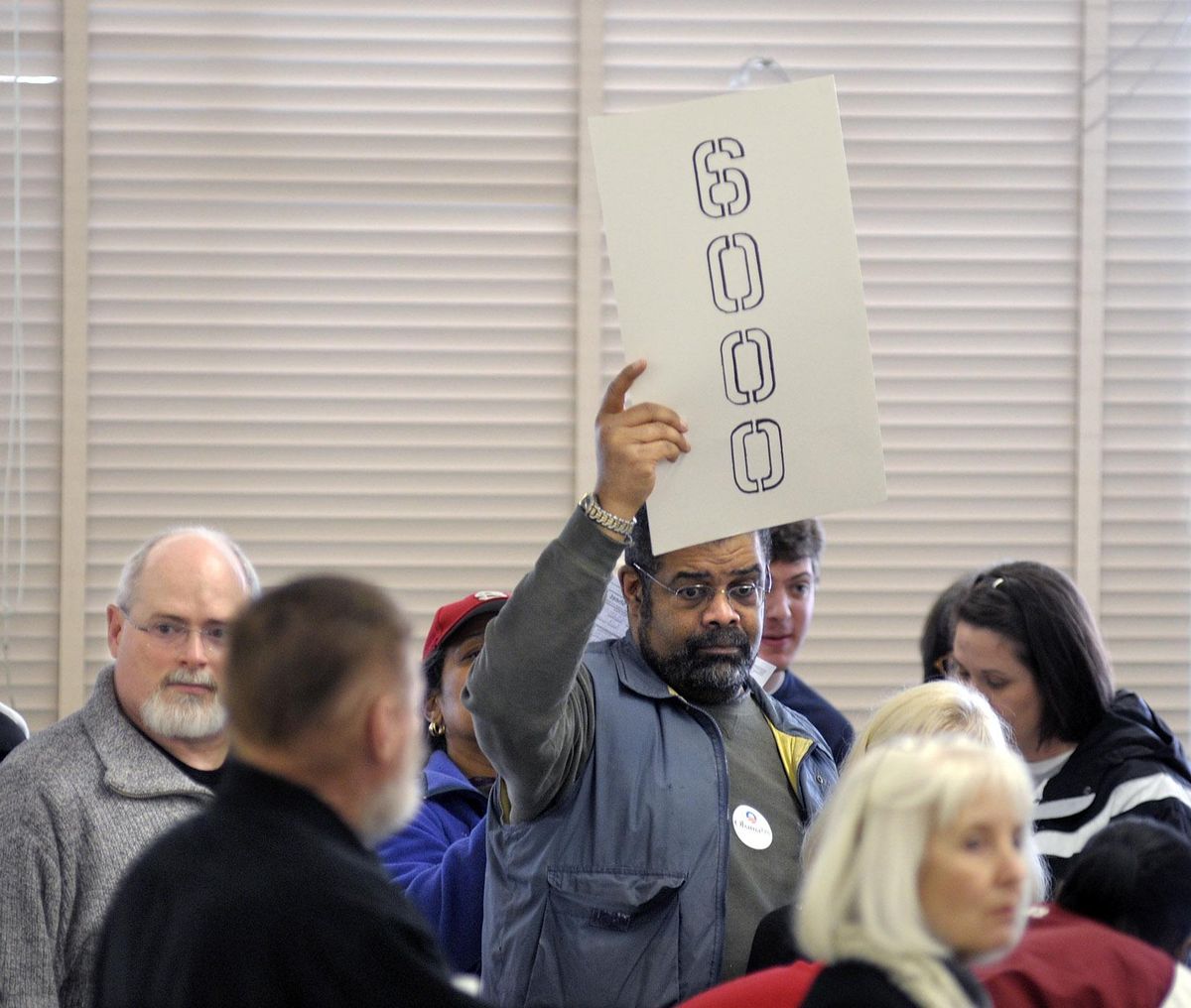

Republicans will start their delegate process with precinct caucuses on Feb. 29, and committed activists will move on through county conventions to the GOP state convention on May 14 through May 16 in Everett. The Republican National Convention starts Aug. 24 in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Democrats will start their delegate process with legislative district caucuses in March and April, followed by county conventions and congressional district caucuses in April and May, and the Democratic state convention in June in Tacoma. The Democratic National convention starts July 13 in Milwaukee.

The presidential election is Nov. 3, 2020, although in Washington voters will be mailed their ballots nearly three weeks before that date, and county elections offices will count ballots received for nearly two weeks after that, provided they are postmarked by Election Day.

But that’s not the end of the process, because the United States doesn’t have a nationwide presidential election. It has presidential elections in the 50 states plus the District of Columbia, which send “electors” to individual Electoral College meetings about six weeks after Election Day. Each state gets a number of electors equal to the total of their two U.S. senators and the number of members in the House of Representatives. That’s a total of 538 electors total, and the candidate who gets at least 270 Electoral College votes is declared the president.

In most cases, all of a state’s electors go to the candidate who got the most votes in the state – even if he or she won by only one vote. Maine and Nebraska have laws that can split their electoral votes if one candidate finished first in a congressional district but another won the overall state vote.

In Washington, which has 12 electoral votes, the parties choose their Electoral College members at their state convention along with their national convention delegates. The party with the presidential candidate who receives the most votes in the November election sends its electors to that December meeting in the state Capitol.

Because they are selected by their party, they usually cast votes for the candidate who won the election. In 2016, however, four of the Democratic electors decided not to vote for Hillary Clinton – who won Washington by more than 500,000 votes, to make a statement by for voting someone else. All were fined $1,000 under the state’s “faithless elector” law – which was enacted in 1977 after Republican elector Mike Padden voted for Ronald Reagan rather than Gerald Ford, who had won the state.

Three of the 2016 electors appealed their fines, saying it violated their right of free speech, but the state Supreme Court upheld the law. By seeking the role of an elector, they were agreeing to follow the state’s rules, the court said.

In 2019, the Legislature changed the law so that any elector who won’t vote for the person who won the state will be automatically replaced by an alternate who will.