The flashier remade U.S. Pavilion is just the latest version of Spokane’s Expo ’74 centerpiece

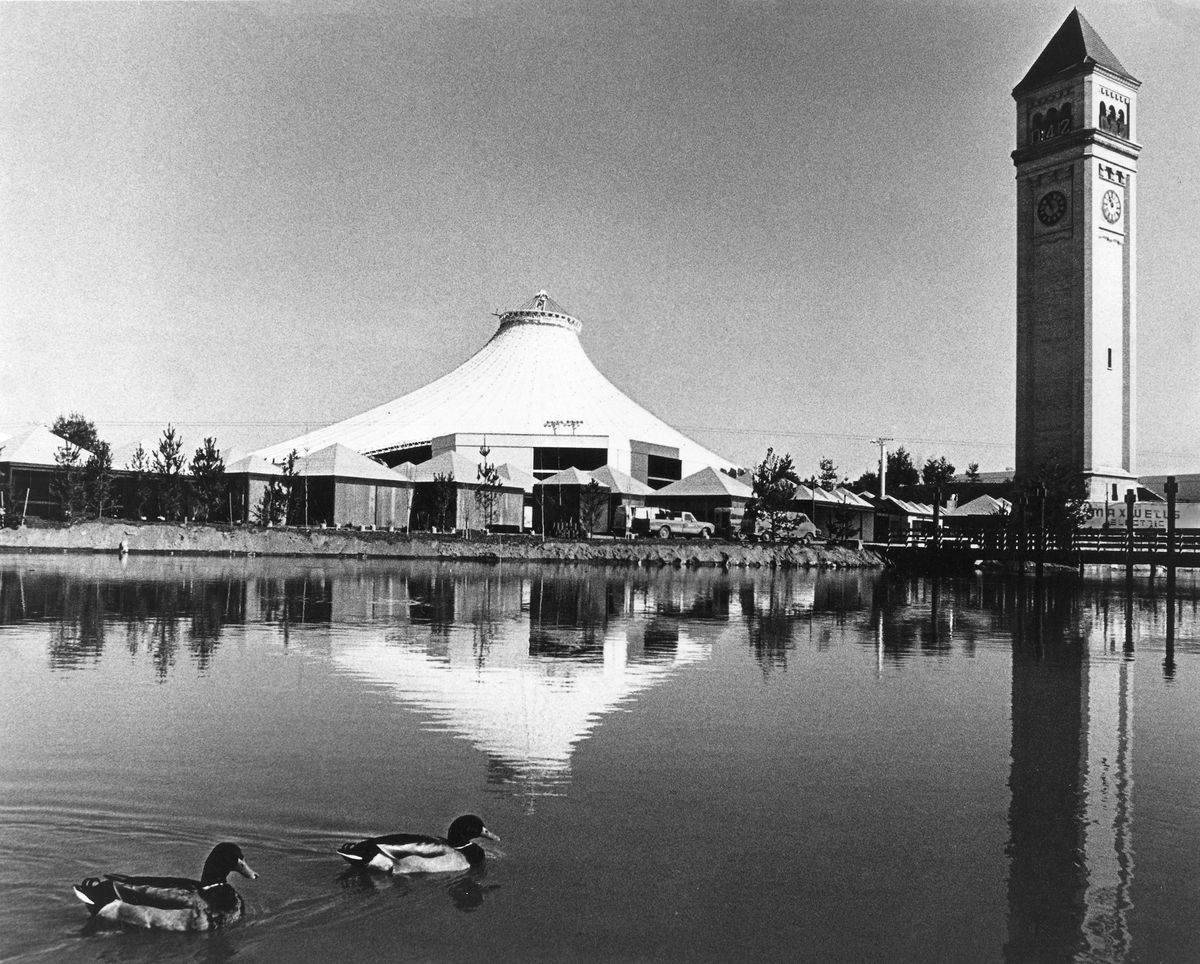

At a world’s fair that celebrated cultures spanning the globe, it’s the U.S. Pavilion, in what became Riverfront Park, that captured the attention not only of Spokane but of all dignitaries visiting Expo ’74.

“Because of its dominant location on the riverfront site and its dramatic architecture, the Federal Pavilion soon became the ‘symbol’ building of Expo ’74,” reads a municipal report, published a year after the world’s fair ended, on the importance of maintaining the building as a permanent part of downtown.

The structure, built on four acres of land the city gave the federal government leading up to the fair, wasn’t envisioned as a building that would last 45 years. Even during Expo ’74, it wasn’t clear what would happen to the structure after the rest of the world’s fair left town.

Preparations for the building, which was to be the centerpiece of the exposition in Spokane, began in earnest in 1972. An early concept for the Pavilion envisioned two conical structures with an open area for exhibition space in between them. The idea included cascading waterfalls from the tops of the two structures with a 1-acre garden and unobstructed views of the Spokane River to the north.

By early 1973, though, architects worried about cost settled upon a final design that included the vinyl fiberglass covering enclosing two permanent buildings, with open-air exhibition space within.

Federal officials attempted to award much of the construction of the structure to local firms, and the design of the project included input from local engineers. The Pavilion’s rings and support systems were designed by Elmer Koivula, a structural engineer who helped develop the B-29 bomber for Boeing Co. during World War II. Koivula died in 1978 at age 74, according to an obituary in The Spokesman-Review that mentioned his contribution to the structure. Koivula lived in Spokane for 30 years before his death.

Throughout the exposition, city officials discussed what to do with the structure when the fair ended. The question received more urgency in June 1975, when President Gerald Ford ordered transfer of the building to the city with no cost.

Almost immediately, city officials began wondering what to do about the covering. That 1975 report envisioned replacing the temporary sheeting, which had already begun to tear, with a more durable cover.

“Investigation and analysis of the Pavilion structure indicate that the existing fabric can be repaired, and with some minor modifications, the structure will be suitable for Spokane’s climactic conditions with a minimum anticipated fabric life of 10 years,” the report read.

By that time, the fabric already had split in several places, including a 50-foot tear during a December 1974 snowstorm. Within three years, the city was considering whether to scrap the vinyl covering due to wear and tear from the weather.

“I feel we’re throwing good money after bad,” Donald Schoedel, a member of the Spokane Park Board, lamented in April 1978, after the city spent $3,000 to repair a tear in the material in advance of a visit by President Jimmy Carter. “It will probably split again with the first good wind.”

The 100,000 square feet of covering were removed by crane in February 1979, and city officials immediately began pondering a potential replacement.

One proposal included covering the structure with concrete, rather than fabric, and plastic skylights. That idea, brought to the city by Chris Kopczynksi of KOP Construction in 1979, would have cost about $2.5 million. But the City Council appeared deadlocked on taking the idea to voters, and the tax plan never went on the ballot.

That summer, the city began selling pieces of the canopy with Expo ’74 symbols for $1.50 each. They also were sold as souvenir bus passes to the Spokane Transit System, as it was known at the time, but the grime of five years of accumulated weather made the project difficult for the printers, according to a story in the Sept. 29, 1979, edition of the Spokane Daily Chronicle.

The issue dragged on throughout 1979 and 1980. In January 1981, city lawmakers voted unanimously to spend a little less than $700,000 on a low-level roof for the skating rink within the Pavilion, rather than a full covering, effectively ending discussion of a cover and giving Spokane its quirky, cabled skyline feature that still exists today.

The skating rink, which opened in November 1977, was just one of many attractions that would fill the building over the next several decades.

Earlier that year, city officials approved a lease for IMAX films to be shown in the Pavilion, and in June 1978 a new theater showing the large-format films opened for business on the site. The theater showed films until 2016, when the Spokane Park Board elected to demolish it as part of the Pavilion’s redesign. Other attractions included miniature golf and amusement rides, which also were proposed for elimination in the 2014 master plan guiding the park’s redevelopment.

Even so, some members of the public, including former Riverfront Park Manager Hal McGlathery, argued to keep the rides as an affordable alternative to other summertime entertainment for local families. Current park planners have brought amusement rides back in a limited capacity on the skating ribbon during the summer months.

Some park users over the years apparently have considered the Pavilion structure its own amusement ride, earning themselves criminal charges in the process. On the first day the Pavilion was open to the public, two men were arrested after sliding down the vinyl covering of the roof, according to an account in the May 3, 1974, edition of the Spokane Daily Chronicle. The men were charged with vagrancy.

And in July 1981, 18-year-old Allen Perkins made headlines for climbing the full height of the 150-foot Pavilion tower, earning himself 40 hours of community service in the process.

When newspaper reporters contacted Perkins’ father, the angry dad told them, “He may not be able to talk about it after his old man gets ahold of him.”

Perkins later gave an interview to reporters, though.

“I’ve led a boring life,” Perkins told The Spokesman-Review on July 13, 1981. “For a kid under 21 there’s nothing to do in this town except cruise Riverside.”