Spokane County gets conflicting reports about nonprofit public defense

Spokane County officials continue to explore the idea of contracting with a nonprofit agency to provide public defense attorneys even though more counties are choosing to make that a function of county government.

Commissioners recently hosted presentations from Snohomish and Chelan counties, which both use the nonprofit model to provide public defense. But local leaders received conflicting messages and outright warnings about trying to shop out a constitutionally-required function to an organization that does not yet exist.

Kathleen Kyle, the managing director of the Snohomish County Public Defender Association, cautioned the Spokane County leaders about potential problems they may face in their effort to spend less money on public defense especially for a county that prosecutes the most drug felony cases in the state.

“I would really caution against that,” Kyle said. “I would work to support your public defenders and not take a step that would undermine their confidence or feeling of support in the county.”

While Commissioner Mary Kuney said she’s still not sold on the idea, both Josh Kerns and Al French continue to pursue it even after hearing about those challenges from Snohomish and Chelan counties.

“I hope for us to make our decision before the end of the year,” Kerns said. “Is this something we want to continue to explore? If not, I think we kind of need to move on. That’s a discussion I’d like to have with my other two seat mates.”

French said he’s received a request from Superior Court judges to meet with the commissioners on the topic.

“We are learning what we can do to see if we can reduce our costs for our taxpayers,” French said. “If this doesn’t generate the opportunities we are trying to generate, then we’ll stay where we are at. But if we don’t ask these questions, we are not doing our job.”

Bucking the trend

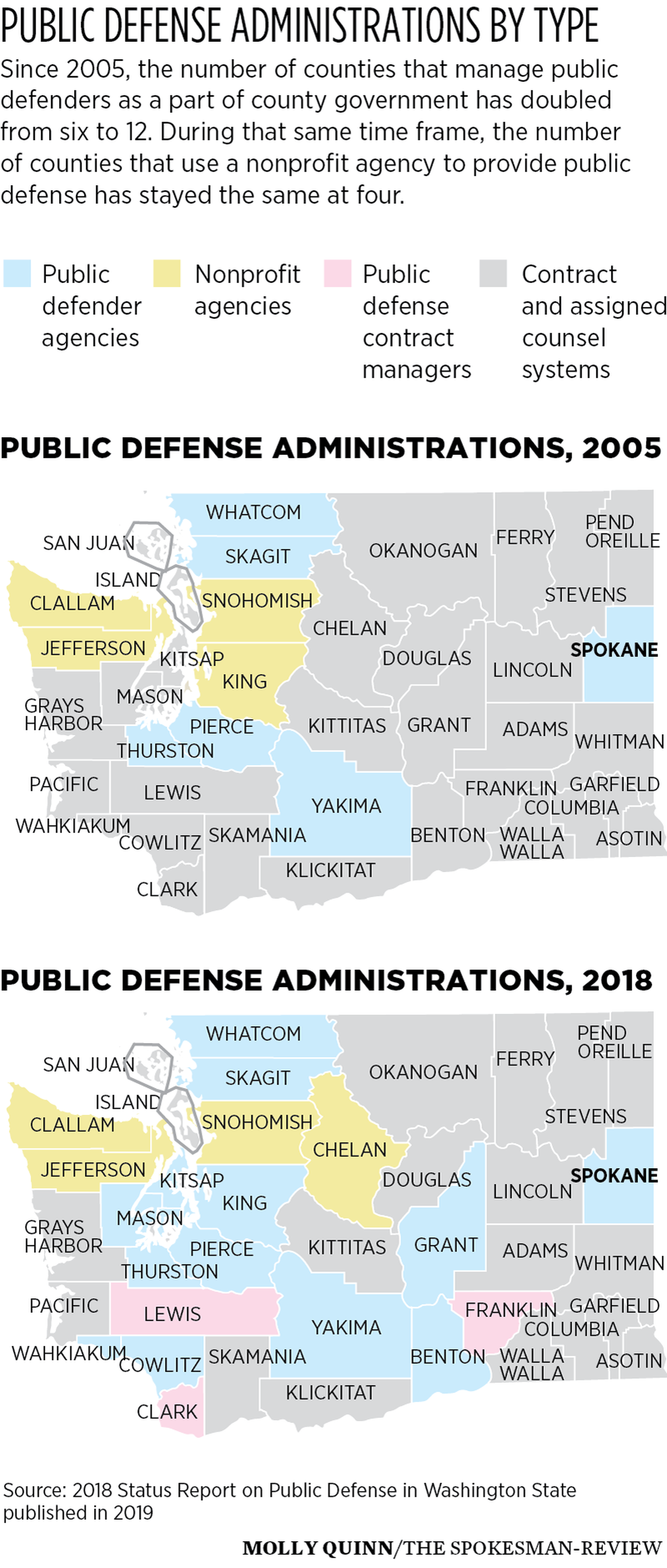

Since 2005, the number of Washington counties that use a nonprofit agency to provide public defense has remained the same – at four. In that time, King County disbanded its effort while Chelan County adopted the nonprofit model in 2006.

Most counties, which involve many of those with small populations like Stevens and Ferry counties, pay attorneys on a contractual basis to provide public defense.

In 2005, only six counties, including Spokane County, provided public defense as part of county government. However, that number had doubled to 12 by 2018, according to the Washington State Office of Public Defense.

Asked why Spokane County would seek to shop the office out to a nonprofit when the state trend is to follow Spokane’s model, French argued that the decision to go to a nonprofit has not yet been made.

“I haven’t heard anything from anybody who said, ‘Don’t do this,’ who is actually doing it,” French said.

But Kyle, from Snohomish County, said that county, which has about 290,000 more people than Spokane County, started its effort in 1973 with five attorneys who would hurry up and cash their Friday paychecks because they weren’t sure they would clear.

“Even though we have a really good relationship with the county, it’s a strained relationship,” she said. “We are not fully meeting all the indigent defense standards.”

According to state figures, Snohomish county provided about $9.7 million for public defense that included about 3,300 felony filings in 2017. In comparison, Spokane County the same year paid $9.6 million for about 4,650 felony cases.

While those numbers don’t reflect Snohomish’s higher number of misdemeanors, most of the officials agreed that felony representation drives the majority of the costs.

In comparison, Chelan County spent $2.3 million and had only 646 reported felonies, or roughly four times the amount per serious reported crime than Spokane County.

Chelan County pays for everything at its nonprofit public defense office from the furniture, the lease on the building to the salaries of the defense attorneys, Chelan County Administrator Cathy Mulhall said.

“Overall, I would say we’ve had a great experience with it and I could highly recommend going there,” Mulhall said. “But of course, the devil is in the details. You are a much larger county than we are. So, sort of leave it at that.”

Grants ‘missed opportunity’

Both Kerns and French previously said they wanted to explore contracting with a nonprofit agency because it would be eligible to receive grants that would be barred from county agencies.

But Mulhall said Chelan County has never received any grants other than those provided by Washington state.

French replied that he couldn’t remember if it was Chelan or Snohomish county that was able to use grant money as “another source of revenue that helped augment their operation.”

But according to Kyle, the managing director in Snohomish County, grants are mostly a non-factor.

She said that the nonprofit organization has only brought in about $4,500 in grants from a church and a bank. The agency uses those limited funds to buy bus tickets for offenders to get home to Yakima or Spokane, she said.

Some “99.9% of our funds come directly from government agencies,” Kyle said.

Kerns said he still thinks the grant option is a plus. He said any prospective contractor in Spokane County would more than pay for someone’s salary if they hired an employee specifically to seek grants.

The grants are “another missed opportunity for the way (Snohomish officials) operate,” Kerns said. “That would be something I would want to see as part of the business model.”

Both French and Kerns earlier this year touted the ability of the nonprofit agencies to hire a pool of attorneys to work normal defense cases and provide that revenue to the agency. The idea would be that the attorneys would be available to defend clients when the caseloads of the other public defenders got too high.

But neither Chelan nor Snohomish counties employ a pool of attorneys who work normal cases.

“That’s something, if you ask me, I think they are missing a great opportunity,” Kerns said. “In our earlier conversation, they told us about that option. But they don’t utilize it.”

Kyle, the managing director at Snohomish County, said she had two good reasons why the nonprofit agency doesn’t allow attorneys to handle normal cases and provide revenue to the office.

“One, that would undermine our status as a nonprofit,” she said. “And two, it would also conflict with our mission to provide representation to indigent defendants.”

‘Rat in the snake’

Kyle told her counterparts that every reaction in the criminal justice system causes a reaction somewhere down the line.

For instance, prosecutors in Snohomish County recently charged a backlog of felony cases from early 2018 that she called “a rat in the snake.”

“That glut slowed the entire court system down. It took us longer to resolve cases,” he said. “We are still seeing the ripple effect now in the fall of 2019.”

That increase in cases required attorneys to work more cases and resulted in defendants staying longer in jail, which also added costs to the county.

“You don’t realize that decreasing funding for public defense actually increases your costs across the board,” she said.