Idaho’s Bees to Bears project hopes this simple idea can combat climate change

A tractor drives through an old farm field on Sept. 19, 2019. Idaho's Bees to Bears Climate Adaptation Project hopes to build better habitat by creating seasonal ponds and shaded slopes. (Eli Francovich / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

As heavy machinery shunted earth, dug pits and generally disturbed a sunny September day, Michael Lucid explained how all this commotion may combat the worst effects of climate change.

“It’s very counterintuitive,” he said of the tumbled dirt and exhaust fumes.

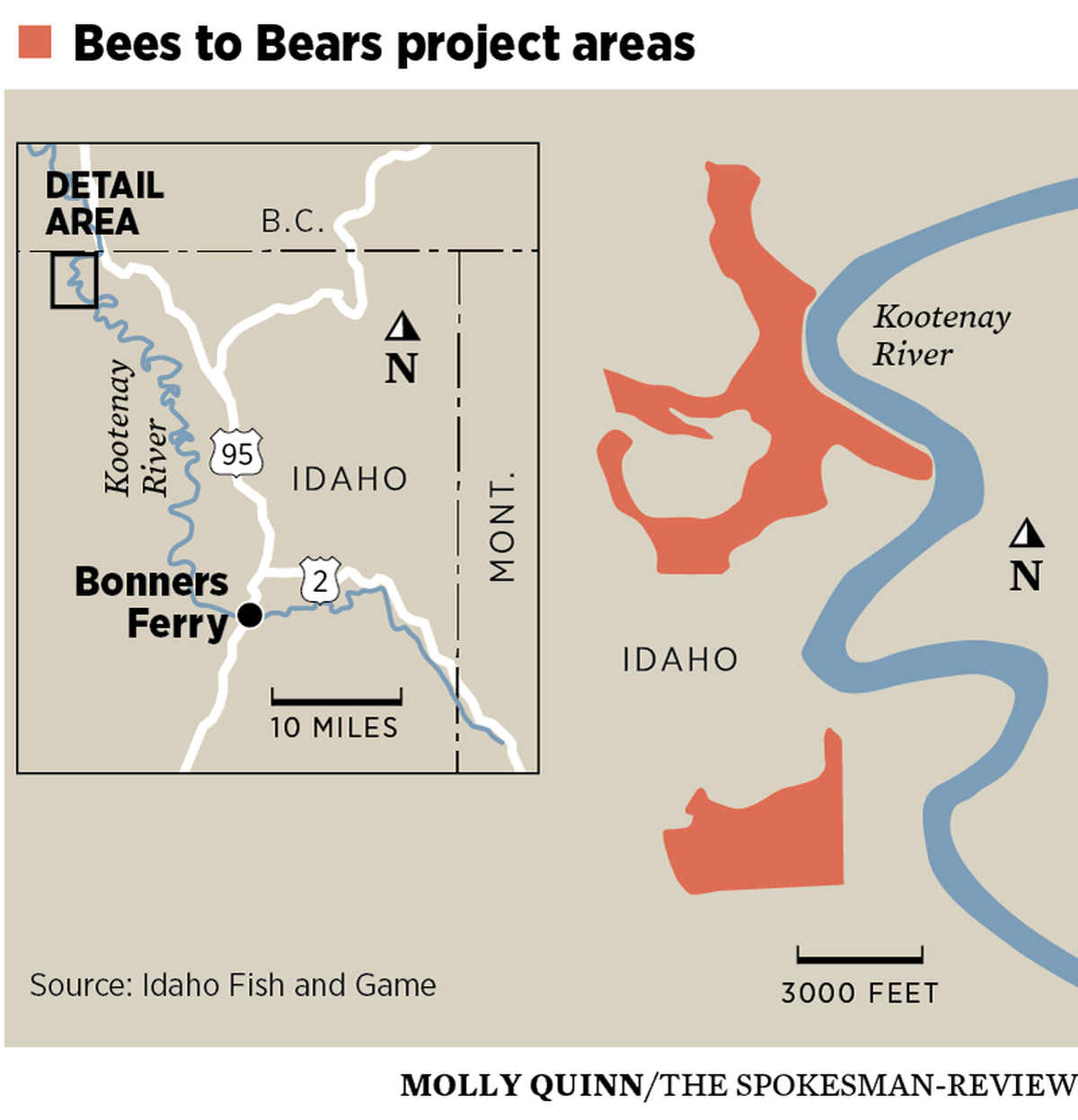

Lucid, who is tall, lean and roughened from a life outside (for five years, he lived off the grid in the Selkirk Mountains), is overseeing the Bees to Bears Climate Adaptation Project in North Idaho’s Boundary-Smith Creek Wildlife Management Area.

The effort is part restoration: The 250 acres north of Bonners Ferry is former wetland dissected and drained by dikes, turned into farm fields and now vacated and dominated by canary grass.

It’s also a test of sorts. Can humans build a landscape better suited for a warming climate?

“This is very experimental,” said Lucid, a biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

The idea is simple: Build mounds of dirt and plant trees and other bushes on top of them. This will provide shade and lower temperatures, the thinking goes.

The technical term for this kind of work is topographic alteration, a “simple concept with a complicated name. We’re basically trying to create shade,” Lucid said.

While the idea may be obvious, its effectiveness has yet to be tested.

“That’s one of the cool things about this project,” Lucid said. “As far as I know, it’s the first time anybody has done this.”

To test its efficacy, IDFG, in partnership with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, built three types of “topographical alterations.” First, a linear mound of dirt about 7 feet tall; second, a curved line of mounded dirt; finally, mounded piles of dirt. They also have control sites with no shade structures.

A tractor drives through an old farm field on Sept. 19, 2019. Idaho's Bees to Bears Climate Adaptation Project hopes to build better habitat by creating seasonal ponds and shaded slopes. (Eli Francovich / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

IDFG has planted 60,000 trees and other native plants on the mounds. As those plants grow, aided by the artificial height, the shade they provide will, they hope, lower overall temperatures.

The shade structures were designed by Brian Heck, an engineer for Ducks Unlimited. Heck said in his 20 years of experience he’s “not seen anything similar to this.”

The unique nature of the project helped it secure some outside grant funding, said Molly Cross, a climate change adaptation coordinator for Wildlife Conservation Society, which awarded the project about $224,000. Overall, the project cost about $550,000. Y2Y funded half with the rest coming from grants. No taxpayer money was spent.

“The microtopography is something that really stood out as a novel and innovative approach,” Cross said. “Really manipulating the landscape.”

In addition to increasing overall climate resilience, the project is designed to benefit a raft of species, including grizzly bears, bumblebees and northern leopard frogs.

The area, while small, is in a key ecological spot. East to west, it’s between the Selkirk and Purcell mountain ecosystems. North to south, it connects ecosystems in southern Canada and North Idaho.

As part of the work, the 250 acres are being restored to how they were before the Kootenay River was dammed and farmers turned floodplains into fields.

The hope, Lucid said, is the cooler temperatures will help bumblebees survive a warming climate, while the trees and shrubs will provides grizzly bear habitat. At the same time, seasonal ponds and streams created by IDFG will act as a buffer against invasive bullfrogs which are threatening a colony of leopard frogs in Creston, British Columbia.

The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative is partnering on the project because the 250 acres are well situated to connect fragmented grizzly habitat, said Jessie Grossman, a project coordination for the Y2Y Initiative.

Additionally, the area is already the coolest in North Idaho, with temperatures 2 degrees lower than elsewhere, on average. It made sense, Grossman said, to enhance that natural climate resilience.

“It’s like a little puzzle piece that can help link the rest together,” Grossman said of the area.

Still, the project is far from a sure bet. The natural world is complex, and managers often find themselves triggering unintended consequences. One generation’s best practices are routinely overturned by the next.

An example of that sort of change in thinking sits next to the current project in North Idaho, a wetland created in the 1990s (also by IDFG and DU) for waterfowl. While that area serves as a stop for migrating ducks and geese, the sides of the wetland, excavated by bulldozers, are too steep for amphibians.

Lucid acknowledges that the current Bees to Bears project is likely missing something “we may learn to add in the future.”

“Regardless, both the waterfowl wetland and the ones we’re building are vast improvements (at least for wildlife) from the farmland and the reed canary grass monoculture,” he said in an email. “And it speaks to why it’s also very important to conserve areas which are largely untouched by humans.”

In a more fundamental way, the Bees to Bears project represents a shift in attitude toward landscape and ecological management.

“I grew up in the generation reading Edward Abbey,” Lucid said. “Like, everything should be pure and just the way it always was, but we don’t really live in a world where things are the way they always were.”

Instead, we live in the Anthropocene, an era in which humans have an outsized impact on the environment, whether that’s changing a river’s hydrology with a dam or increasing global temperatures via carbon.

“One of the newer ways of thinking in ecology is that our goal is not necessarily trying to re-create a prehuman world – but helping wildlife (and ourselves) adapt to conditions which are changing more quickly than the evolutionary process can keep up with (because humans changed the game),” he said in an email. “That’s where the cool air refugia come in. Those are nowhere near ‘natural’ conditions. They are, in our estimate, something that will give bumblebees an edge as summers get hotter, drier and longer.”