Businessman and aviation enthusiast opening flying museum at Felts Field

Johns Sessions, a Shadle Park graduate, created the Historic Flight Foundation and is moving his museum with many of his vintage planes to a new hangar at Felts Field. Sessions is sitting on the wing of his Staggerwing Beechcraft Model D17s built in the 1930s. (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

John Sessions doesn’t have a favorite airplane.

He has three.

That’s understandable, considering he owns many historic aircraft – a Douglas DC-3, Supermarine Spitfire IX and a Grumman F7F Tigercat among them. Still, as he describes his favorite craft, it’s less about the plane and more about the place.

“On a warm summer evening, when you’re feeling good, any open cockpit biplane while tracing a river to its source is hard to beat,” he said.

When it comes to “elegance and history,” it’s the Spitfire, a single-seater fighter used by the Royal Air Force during World War II, though Sessions’ came from the post-war Czechoslovak Air Force. Lastly, those days when early Bob Seger is on the radio and he has the urge to “let the ponies run,” nothing tops the Tigercat, a powerful twin-engine fighter used as a night attacker during the Korean War.

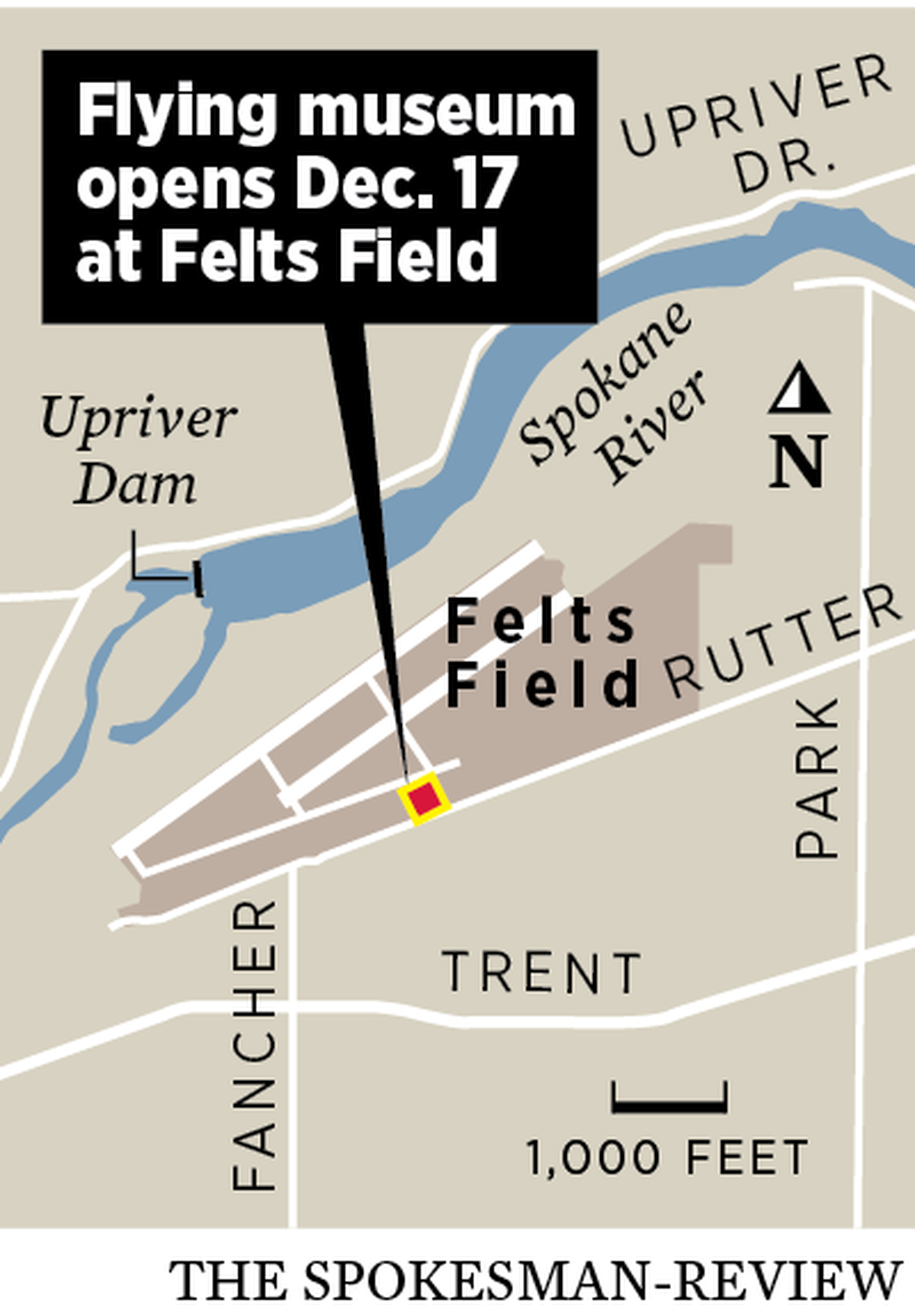

Sessions is the Seattle businessman behind the Historic Flight Foundation, so he knows his stuff. He founded the “flying” museum in 2003 as a way to collect and restore significant aircraft, and give people an opportunity to fly in planes many thought were relegated to the history books. The collection has always been housed at Paine Field in Snohomish County, but now it’s coming to Felts Field in Spokane, which will be the museum’s second location.

The Spokane expansion came about as Sessions’ collection grew and he began casting about for another location in 2016. He asked 25 airports in the Pacific Northwest if they were interested, and nine sent back “wonderful” responses,” he said. Though Sessions was born and raised in Spokane, and graduated from Shadle High School in 1971, he said that didn’t really figure into why Spokane was chosen. It was the airport that did it.

“We liked the fact that Felts had the history it has,” he said, jumping into a quick primer on how runways used to be unpaved, grassy fields, with just a “sock” to tell pilots which way to land.

“Felts Field was a field. Hopefully it was mowed recently,” he said. “But we love the heritage of the place and the fact that the heritage is being preserved.”

In this June 2, 2017 photo, a DC-3, dressed in the livery of Pan Am airlines and operated by the Historic Flight Foundation, parks on the ramp at Felts Field, Friday, June 2, 2017, in preparation for Neighbor Day. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

When it officially opens this December, the flying museum will have nine airworthy planes. The new hangar on Rutter Avenue is already filling up. A Beechcraft Model D17S Staggerwing gleams cherry red in one corner. Opposite it sits a Travel Air NC9084, a utility aircraft often used by bush pilots in Alaska that was marketed as the “limousine of the skies” thanks to its on-board toilet. There’s the Hamilton H-47 Metalplane, built in 1929 as one of the first passenger airplanes. And there’s the Stearman Kaydet, a two-seater biplane that Sessions bought from the family that had owned it since 1946.

More are on their way, and Sessions has two months between an Oct. 17 fundraising gala and the opening date of Dec. 17 to get the museum airworthy, so to speak.

It’s just one of the many challenges Sessions has before him – a relatively easy undertaking considering what he’s dealt with over the last year.

On Aug. 11 2018, Sessions was giving pleasure flights aboard a de Havilland Dragon Rapide in British Columbia. The weather was changing, and a crosswind had picked up. Upon takeoff, the right wing touched the ground and the plane chewed into the tarmac. He looked down. His left foot had been snapped off and was still in the boot. His leg was bleeding. He used his belt as a tourniquet and helped two people from the plane. He said his emergency training saved his life. Without quick thinking, he would have bled out in minutes.

“In a second, your life is reshaped,” Sessions said. “We know that doing this thing, there are going to be bad days where we or are friends suffer. One the balance, it’s worth it.”

Sessions was friends with Ernest “Mac” McCauley, the pilot aboard the B-17 Flying Fortress that crashed during an emergency landing at a Connecticut airport, killing him, the co-pilot and five others.

By March 2019, seven months after his crash, Sessions was ready to fly again. His proficiency check was a transatlantic flight on his DC-3 as part of the D-Day Squadron commemorating the 75th anniversary of D-Day and the Berlin Airlift.

Sessions got bit by the flying bug when he was a corporate lawyer working for Boeing. After working an all nighter on a Boeing case in 1983, he went to breakfast at Boeing Field. He met an instructor with room in his schedule for another student.

“So I started taking lessons at a flying club, then it got out of hand,” he said.

His lawyer work turned into California real estate work, and Sessions kept flying. He spent 10 years in the arctic flying bush planes, and advanced from piston to turboprop to jet engines.

“I got tired of the bad weather, so I kept going higher,” he said. He delved into historic airplanes, to warbirds then to doing aerobatic displays at airshows. Through it all, he found the golden era of airplane innovation, the focus of his museum.

The planes in Sessions’ collection were all built between 1927 and 1957 – a 30-year span book-ended by Charles Lindbergh’s pioneering solo transatlantic flight and the first Atlantic journey by the jet airliner Boeing 707.

“Much really hasn’t improved since then,” Sessions said. “It’s just gotten cheaper.”

Just think of it. In 1927, Lindbergh was the first person to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. More than 33 hours after leaving Roosevelt Field on Long Island, the lone pilot touched down on the tarmac of LeBourget in Paris. The Spirit of St. Louis, his custom-built, single-wing single-seater was the opposite of comfortable. The cramped cockpit was not big enough for the lanky Lindbergh, and there was no front window. To see forward, Lindbergh had a periscope to peep through, or would yaw the plane some for side eye. Top speed was 120 mph.

Thirty years later, the 707 introduced the world to the jet age with the first commercial jet transportation. It too crossed the Atlantic – with room for 140 passengers and as “one of the most glamorous of all forms of transport,” according to a 2014 retrospective of the plane by the BBC. Top speed was nearly 600 mph.

This 30-year era of innovation is what Sessions wants to celebrate. His museum will be a “procession of technology and a person associated with it,” which he will use to educate and inspire people. He wants his museum to be a place where children interested in science, technology, engineering and math can marvel at invention and imagination.

“The old planes are a kind of metaphor,” he said. “There’s another 1927 out there. Not in aviation, but it’s out there.”