What’s in a dam? National report cites high hazards near Spokane, but none are threatening life, property

The undeveloped southeastern edge of Newman Lake is a dike to keep the lake out of the adjacent fields, shown Wednesday, Nov. 20. The earthen dike is on a list of dams that are considered failing. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

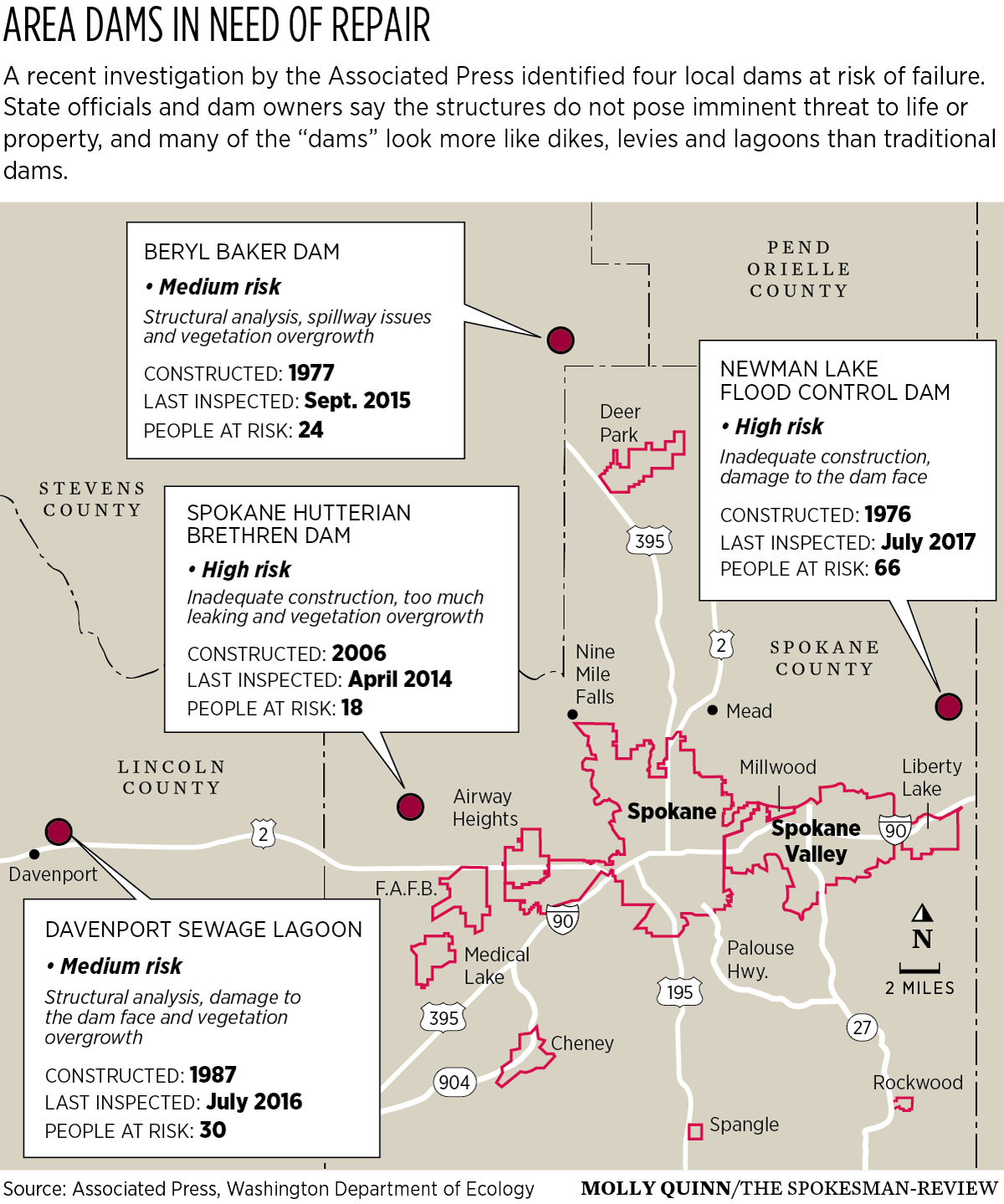

Four dams identified as having a high risk of failure in a recent national Associated Press investigation lie within 50 miles of downtown Spokane.

But none of those dams, or any of the dozens of others across Washington state, is posing an imminent threat to life or property, said Joe Witczak, dam safety manager in the Department of Ecology’s Water Resources division.

“We look at worst-case scenarios,” said Witczak, whose team prepares an annual report to the Washington Legislature on the state of more than 1,000 dams that fall under the Ecology Department’s jurisdiction. “We base a high-hazard dam on that catastrophic, top-to-bottom failure, when everything blows at once.”

A little less than half of Washington’s dams fall into the high-hazard category, threatening at least three homes should the levee break. Those dams are inspected every five years by law. Of those, 44 (about 11%) are in poor or unsatisfactory condition, according to state experts.

The dams falling into this category near Spokane are not massive concrete structures that the public would quickly identify as a dam. They are smaller, earthen structures used to pond water for fire suppression, collect treated sewage for agriculture irrigation or provide recreation opportunities in the summer. Solving the potential problems caused by dam failure in the region is not as urgent as life-or-death scenarios caused by walls of water, but they do demonstrate the complexities of property rights and the public’s expectations about waterways and what constitutes a dam.

The Newman Lake ‘dam’ – or is it ‘levee,’ or ‘dike’?

What to call the mound of peat trapping the waters of Newman Lake depends on whom you ask.

According to the Washington Department of Ecology, that mound is a dam.

“What we look at, is whenever something artificial is holding back 10 acre feet of water, or some of type of liquid,” said Witczak. “That’s about 3.25 million gallons.”

Dennis Rewrinkle, a longtime resident, engineer and member of the Newman Lake Flood Control Advisory Board, prefers the term “levee.”

“Man didn’t do this,” Rewrinkle said of the 1,200-acre lake that is filled annually by snow melt runoff from Mt. Spokane. “God did this when he shoved that ice cube down the valley.”

The ice cube he’s referring to is the lobe of glacial ice that stretched from British Columbia into the Inland Northwest, carving valleys and triggering catastrophic floods. In the late 19th century farmers first began piling peat onto the lake’s southeastern edge in an effort to keep flooding from the lake from encroaching onto hayfields during heavy rains and snowmelt.

In 1968, property owners on the lake banded together to create a taxing district that now raises some money for flood control. The idea was to keep a predictable amount of water in the lake for those choosing to boat, swim or fish.

Today, the largest portion of the money they pay instead goes toward improving water quality on the lake, which experiences frequent algae blooms. The level of the lake is controlled by a floodgate, managed by Spokane County on its southeastern edge, near a public access point owned by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Until a heavy rainstorm a few years ago that caused localized flooding, the structure was not considered a high hazard dam, said Colleen Little, a civil engineer with Spokane County who serves as manager of the flood control district. But an inspection after the flooding showed the peat was not level and had degraded from wildlife activity, prompting directives from the state to seek a more permanent solution to potential future flooding, she said.

“The entire dam is made of peat, and it’s going to continue to subside over time,” said Little, who prefers the term “dike” to refer to the mound on the lake’s southern edge.

The Ecology Department says if the peat dam were to fail, rising waters would threaten more than 20 structures and up to 66 people. But that water would rise slowly, Rewrinkle said, filling a spillway carved along an access road and a 40-acre sump before the water level rose and filled the valley south to Trent Avenue.

“To make Newman Lake a dam, in my own personal estimation, is just ludicrous,” Rewrinkle said. “The hayfields below the dam that we were trying to keep dry so they can harvest hay – those have, for the most part, been abandoned.”

Any improvements to the dam would fall upon the district’s roughly 770 ratepayers to fund. Lee Tate, another longtime resident and advisory board member, said he’s heard estimates on installing a permanent dam on the site costing anywhere from $6 million to $16 million, depending on the unknown depth of the peat now holding the water back.

That’s a potential cost of between $7,800 and $21,000 per rate-payer.

“The people would really squawk if they had to pay that,” said Tate. That’s because those who would be responsible for footing the bill aren’t the ones whose property would be slowly flooded if the natural dam failed; it’s the residents closer to Trent, who don’t pay flood control assessments and may be unaware they’re living in a potential flood plain.

Witczak, with the Ecology Department, called the scenario “risk creep.” It’s when the potential danger posed by flooding falls upon people who aren’t responsible for paying to prevent it from happening, and it’s not unique to Newman Lake, he said.

“There’s this subtle earthen thing, and then we show up at their door and say, ‘Surprise, you’re a dam owner,’” Witczak said.

Spokane County Commissioner Josh Kerns, whose district includes Newman Lake, said he empathized with the concerns about affordability for Newman Lake residents. It would also be unlikely the county would have the funds to assist with construction of a dam, he said.

“I would expect we would be going to the state, and look at whether capital budget funds are available,” Kerns said.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is preparing a report on the behavior of floodwaters, should residents and Spokane County choose to remove the peat that has been piled on the southeastern border of the lake and return it to its natural state.

Doing so would remove the structure from Ecology’s list of high-hazard dams, because a dam wouldn’t exist there anymore under the department’s definition. The runoff would filter through the existing channel, sump and wetland system there, rather than being inundated should the pile of peat be breached.

No news on Hutterian dam near Deep Creek

The towering earthen dam on the southeastern edge of property owned by the Hutterian Brethren of Spokane has been on state regulators’ radar for more than a decade.

The Ecology Department’s dam safety program first inspected the 30-foot-tall span in 2009, after the commune piled earth to trap a collection pond on a tributary of Deep Creek, 14 miles west of Spokane. They returned, as required by law, five years later, but did not prepare a report to share with the Hutterites about continued deficiencies in their dam, Witczak said.

“They went out and took pictures, left their field notes,” Witczak said. “But we did not have a formal report to give to them, saying here are the problems you need to fix.”

As a result, the community has operated under the assumption their dam had passed safety inspections. The Hutterites even hired a geotechnical firm out of Idaho to drill test wells into their dam to check for leaks, said Paul Gross, who helped oversee construction of the dam more than a decade ago.

“Everything is quiet,” said Philip Gross, Paul Gross’ cousin and a representative of the community. “We’ve had no new issues.”

Ecology officials rechecked the well in May, and will issue a new report early next year on the safety of the dam. Paul Gross said the water trapped is for emergency purposes, including fire suppression at a nearby school, and as a place for waterfowl and wildlife. The water collected is not used for domestic purposes.

Still, because of the lack of an official report from five years ago, the Hutterian dam remains on the state’s list of high-risk dams due to its lack of construction permits, concerns about seepage and vegetation growing on the dam, according to the 2018 Ecology report. A total of 18 people, or six homes, lie within the flood path should the dam fail.

If it does, the water would fall down a spillway and through a valley lining up with local, gravel roads. The channel connects with Deep Creek just south of North Deep Creek Road, a few miles north of Highway 2.

“That’s one we need to pick up our communication with,” said Witczak of the Hutterian dam, noting that his department just received funding for an additional staff person whose only job is to follow up with dam owners whose infrastructure has been designated as at a high risk.

Help in the form of federal grants?

The other two dams on the Associated Press’s list include a sewer lagoon just north of the town of Davenport in Lincoln County, and a private dam on land preserved for conservation by the estate of an investment banker and philanthropist from Spokane.

The lagoon was part of a public works project intending to meet new ecological standards for sewage treatment and runoff; the system was built between 1987 and 1993, said Fred Bell, Davenport’s maintenance superintendent. The city worked with Ecology after an inspection in July 2016 and has built a new spillway that is intended to withstand historical rainstorms.

“There were a number of items they requested we do, and we have taken care of them,” Bell said.

Both the sewage lagoon and the dam in southern Stevens County are considered at a lower deficiency level than the dams on Newman Lake and the Hutterite property, but both still are close enough to occupied homes that the Ecology Department is inspecting them on a five-year basis.

The private dam is on property that was purchased and dammed by Beryl Baker, an investment banker who in 2009 put more than 1,300 acres of private timberland into conservation protection. When Baker died in 2017, his family spread his ashes on the private dam, named “Ponderosa” for the ranch on the classic TV show “Bonanza.”

The Department of Ecology puts the dam, built in 1977, at risk of failure due to spillway and vegetation issues. A catastrophic failure would put 24 people, or eight homes, at risk of flood. It’s located in a rural area just east of Loon Lake on Gardenspot Road, about 32 miles north of downtown Spokane.

Raising money for repairs can be difficult for private property owners who don’t have access to the same grants and funding opportunities by governments, Witczak said.

“Dams owned by cities and counties, and the state, they have more resources to bear than ones that are owned by an individual,” he said.

That could soon change, as for the first time in 2019 the state received funding directly from the Federal Emergency Management Agency intended to address deficiency concerns at state dams. Of the $10 million set aside by Congress for the federal agency to award in 2019, the state’s Department of Ecology received $153,007 for work on dams in Aberdeen and Newcastle.

Some of that money next year could go toward whatever option residents and the county choose to pursue on Newman Lake, said Little, the county engineer.

“Whatever option we choose, it’s not going to be inexpensive,” she said.

Private property owners could apply for the program, Witczak said, but they’ll need a local nonprofit or government to sponsor them.

That $10 million amount is about .01% of the $70 billion the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, a national professional group of dam experts, estimates repairing the country’s aging dams will cost. Witczak said the hope is that, with the success of initial dam repair projects, that pot will continue to grow and avoid the type of failures highlighted by the AP.

“They’re pointing out, the nation’s infrastructure, it’s getting old,” Witczak said. “It’s saying, people, you’re at the 50-year mark. A lot of the things that are built, that 50-year time frame, you want something to last at least that long. But repairing it, who’s going to pay?”