By the time Hotel magazine ran a long profile of the Davenport Hotel in April 1917, the landmark in downtown Spokane had been open just a few years.

The glowing article described Louis Davenport as a “constructive dreamer” with a “creative genius and untiring energy” before delving deep into the many features of the new hotel: Davenport’s famous restaurant, billiard parlors, coffee shop, bowling alleys and the “proposed Turkish bath and swimming pool.” It lauded the use of “mechanical refrigeration” throughout the building, and approved of the extra touches for motorists, including “sanitary ice cream containers insulated with ground cork, which keep the cream in perfect condition for about five hours” and “box and basket lunches.”

Besides Davenport, the article assigned credit for this “remarkable new refreshment palace” that caused any who entered it to exclaim in “surprise and delight at its rare beauty” to one man: Gustav Albin Pehrson.

“He has worked early and late in the consummation of these plans, and is responsible for many of the unusual architectural features and pleasingly harmonious effects obtained,” the article said of the Swedish-born architect.

Ten years later, the April 17, 1927 edition of The Spokesman-Review ran a brief profile of Pehrson, who had made Spokane home two decades before. Not only had Pehrson been superintendent of construction of the Davenport more than a decade before, the article said, but he “also had charge of the designing and making of plans.”

During the following decades, Pehrson would doggedly claim credit for the hotel in ads he ran in the Spokesman and Spokane Daily Chronicle. In 1941, he wrote that his “designing and work is to be found in the Davenport Hotel” in a brief autobiography kept in his family’s archives.

Yet, to this day, when the hotel and its history are spoken of, Pehrson is rarely mentioned. Instead – in books, websites, news articles and documentaries – the Davenport is described as a monument to the architect often credited with designing early Spokane: Kirtland Cutter.

The hotel’s website, on its “History & Architecture” page, proclaims that the “Historic Davenport Hotel is a regional landmark and masterpiece of the acclaimed architect Kirtland Cutter.” Pehrson’s name is not mentioned.

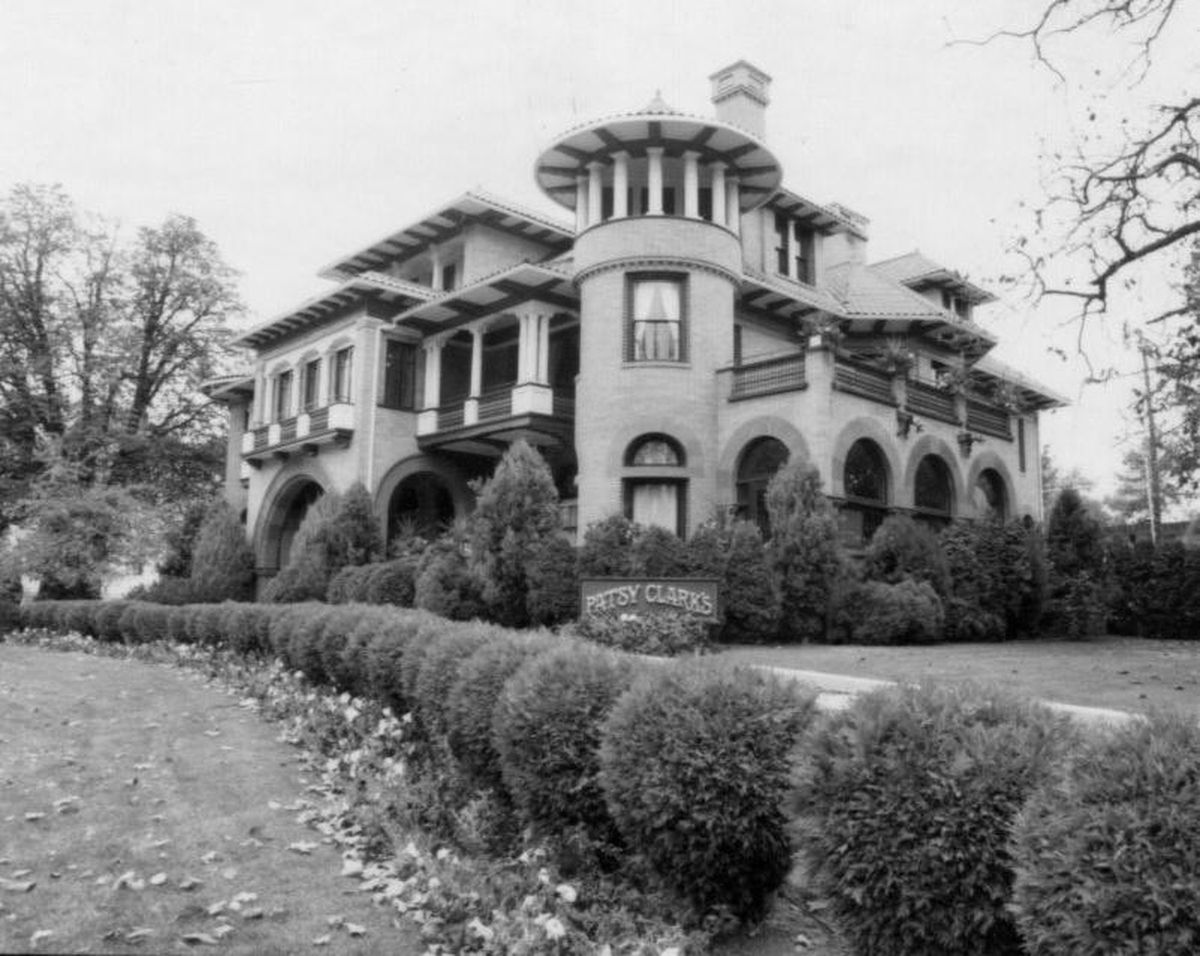

Patsy Clark Mansion built in 1898 (The Spokesman-Review photo archive / SR)

Cutter has a list of buildings and structures in Spokane that is dizzying in its breadth. The Glover Mansion, Patsy Clark Mansion, Spokane Club and Monroe Street Bridge were of his design, as were Seattle’s Rainier Club, the Cutter Theatre in Metaline Falls and the Idaho Building for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Cutter’s list of accomplishments usually contains the Davenport Hotel. If Bob Lawrence has his way, it won’t anymore.

Lawrence is Pehrson’s grandson. He remembers sitting on his “Baba’s” knee, and listening to the Swedish accent that stayed with him until his death in 1968. And he remembers what his grandmother, Bess Pehrson, used to say about her husband.

“Your grandfather was the real architect of the Davenport Hotel,” she said. “Not Cutter.”

Now, armed with Pehrson’s archives, Lawrence is on a quest to get his grandfather the recognition he deserves.

“I’m beyond frustration. It’s like a game now,” Lawrence said. “There are so many buildings that are undeniably Pehrson buildings. But with other buildings, like the historic Davenport and Spokane Club, there is some haziness. I just want to give him credit for the things he did do, and not give him credit for the things he didn’t do.”

Known from Chicago to San Francisco

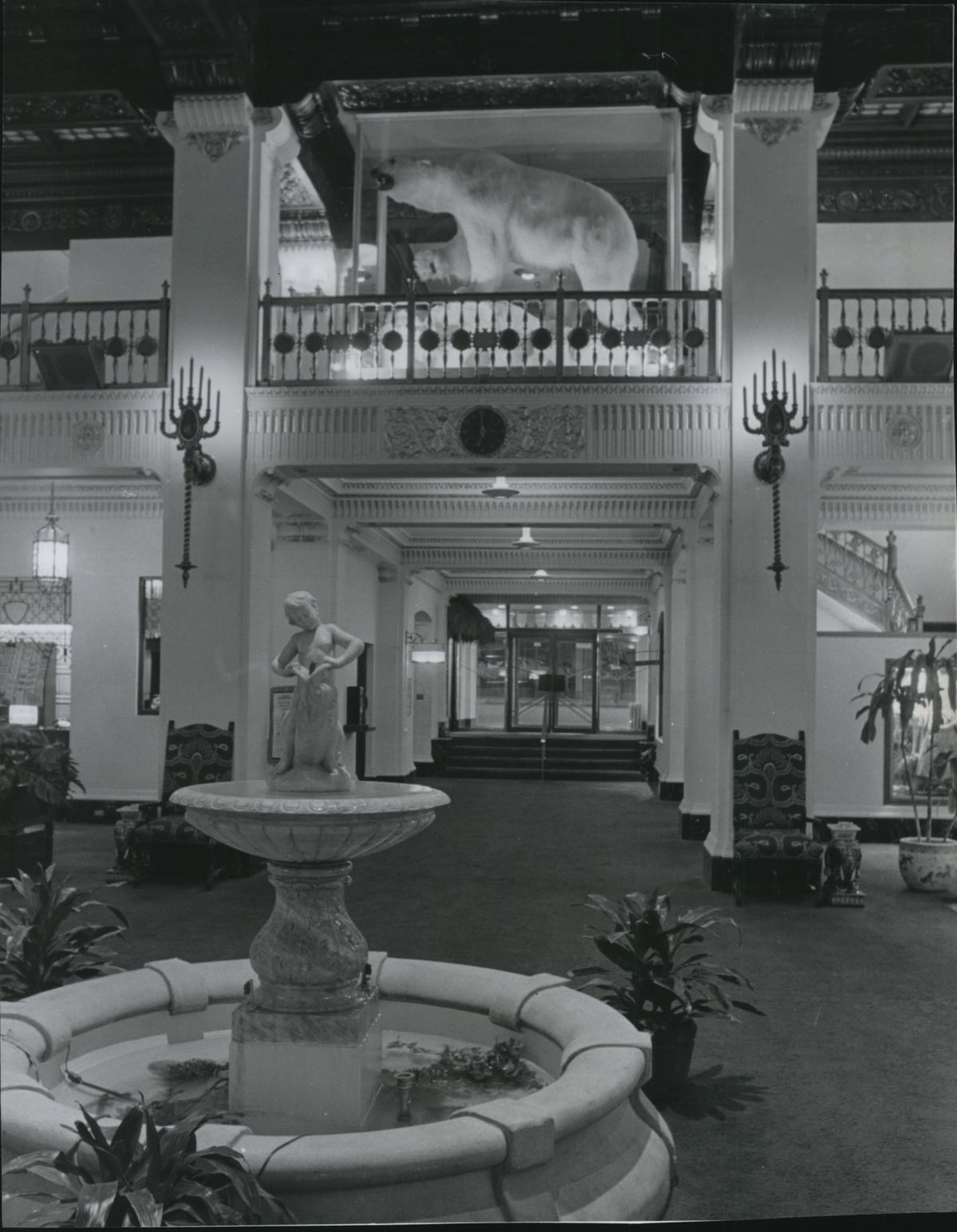

The Davenport is perhaps the most celebrated of Spokane’s buildings. Its grandeur delivered prestige to the young city when it opened in 1914. Its collapse and near demolition in the 1980s and ’90s reflected the city’s own struggles, as did its renovation and resurgence in the past two decades. Its lobby remains luxurious and comfortable, and is something of a public space for travelers and locals alike.

The novelist Will Irwin said the two best hotels in the world were the Davenport and Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo. The Davenport famously has a cameo in Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon.” Nancy Gale Compau, a local historian who long ran the Spokane Public Library’s Northwest Room, said the “history of the Davenport Hotel is the history of Spokane.”

From the very beginning, Cutter was there.

Though now it occupies an entire city block, the Davenport began in 1889 as “a pair of fairly anonymous brick buildings,” according to the building’s nomination to the National Registry of Historic Places. Louis Davenport had come to Spokane the same year to work for his uncle, Elijah Davenport, at the Pride of Spokane restaurant. After the Great Fire of 1889 destroyed the restaurant and most of downtown, Davenport opened his short-lived Waffle Foundry in a tent among the ashes.

Within a year, he opened his restaurant on West Sprague Avenue – where it remained and expanded, and where the Davenport sits to this day.

Facing Sprague Avenue before the construction of the Davenport Hotel on the block, there were, right to left, the Allen Building, two small buildings with a grocery and a bakery and the Pfister bar, which stretched from Sprague to First Avenue. At far left is Louis Davenport’s two-story restaurant, which was incorporated into the hotel. (SPOKESMAN-REVIEW PHOTO ARCHIVE / SR)

From its start, Davenport’s was described as the city’s “leading and popular restaurant,” and Davenport himself saw his reputation and wealth grow.

In December 1895, the Spokesman said the restaurant was “known from Chicago to San Francisco,” and pronounced that “one may travel a thousand miles in any direction without encountering a restaurant that can approach Spokane’s palatial establishment.” In January 1896, the Chronicle said Davenport was “very popular in the city and the institution he has built up is not only an honor to Spokane but reflects the highest credit upon himself.”

By 1900, Davenport had taken over the entire east end of the block and was among the city’s elite. Flush with cash and in need of a remodel, he hired Cutter.

Cutter had arrived in Spokane three years before Davenport, but had a similar, successful trajectory. After studying painting and sculpture at the Art Students’ League in New York, he traveled Europe and landed in Spokane in 1886, where he worked for his uncle, Horace Cutter, a banker.

“Cutter’s charm and enthusiasm, as well as his talent for making beguiling sketches, may have been the key to obtaining commissions from Horace Cutter’s business partners,” wrote Henry Matthews in an essay about Cutter in the book, “Spokane & The Inland Empire.”

In 1889, at the age of 29 and with no real architectural training, Cutter began designing mansions for James Glover, president of First National Bank of Spokane and the so-called father of Spokane, and Frank Rockwood Moore, the first president of Washington Water Power Co.

By the time Davenport hired him to redesign his restaurant, Cutter already had done some renovation work on the restaurant, transforming it into the Italian Gardens, and was the man the city’s upper crust went to for their palatial homes, including John Finch, Amasa Campbell, Jay Graves, Daniel Corbin and Patrick “Patsy” Clark.

At the turn of the century at Davenport’s request, Cutter remade the restaurant again, and Cutter completely reclad the building in white stucco and roofed it with red tile. Tall arches on solid piers were punctuated with “jaunty little gables breaking the eaves,” Matthews wrote.

Davenport’s success kept up, as did his relationship with Cutter. In 1903, Davenport acquired more of the block and turned to Cutter to design the Hall of the Doges above his restaurant. The ballroom remains in today’s Davenport.

But the biggest partnership was made official in 1908, when the news broke that Davenport was leading a group of business owners to bring a large, upscale hotel downtown.

On Oct. 11, 1908, the Spokesman ran a front page illustration of Davenport’s proposed, $1.75 million hotel – hand drawn by Cutter in the Mission-style of the existing restaurant, with parapets, arches and towers “but more lavish in its ornamental trimmings,” according to the book, “Spokane’s Legendary Davenport Hotel” by Tony and Suzanne Bamonte. The article accompanying the illustration said Cutter and Davenport would soon “make an extended trip east” to “make a study of big hotels.”

Pehrson arrives in Spokane

There’s a good chance Gustav Pehrson grabbed the newspaper when the Davenport hit the front page. He was, after all, working for Cutter.

Pehrson was born in Karlstad, Sweden, in 1884 and went to Uppsala University, where he studied architecture. After a two-year stint at a technical college in Stockholm, Pehrson “traveled all the countries of the continent and the British Isles studying the many different types and traditions of his field, architecture.”

In 1905, he came to the United States on a yearlong trip and eventually reached Spokane, thanks to Swedish acquaintances he had in Newman Lake. He spent several months working in Cutter’s office. At the end of his year abroad, he went home, but “a restless urge brought him back to the United States and to Spokane the next year” in 1906, according to his short autobiography.

He was drawn to America because he could be more inventive with his work.

“The country was expanding, but in Sweden, there were too many set traditions in building,” he wrote.

Again, the European-trained architect was hired by Cutter.

Unlike Cutter and his well-known catalog of work, it’s hard to know what Pehrson was working on during this time. He was a young, single immigrant working for a well-known city leader. In a questionnaire he filled out for the Spokane school district in 1941, he said he was “in charge of such work as Spokane Club Building … House for Mr. L.M. Davenport at 8th avenue, together with several other projects.”

Pehrson’s anonymity would dissipate with the Davenport.

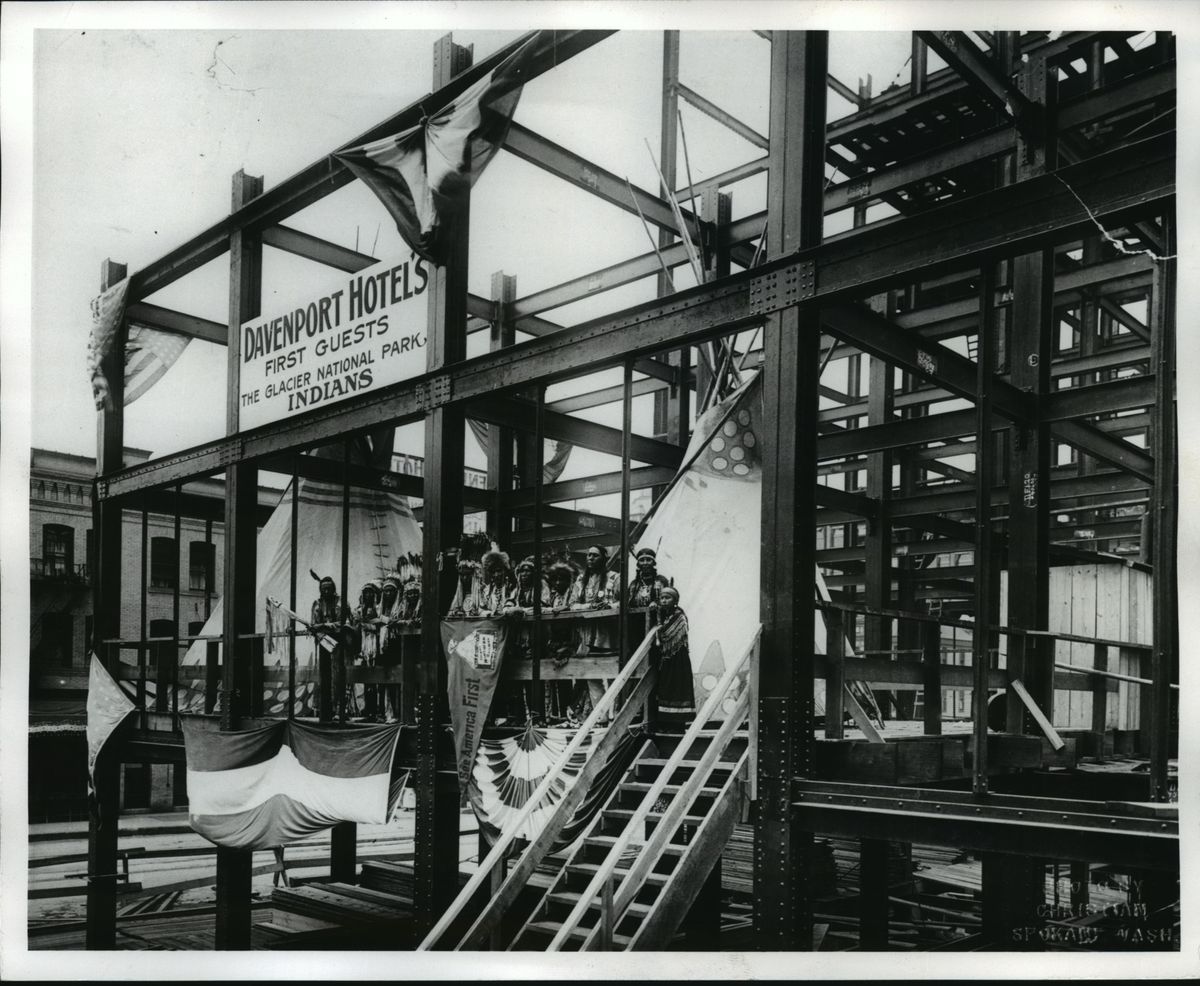

One of the earliest mentions of Pehrson in the Spokesman came on March 19, 1913. Work had yet to begin on the hotel. Davenport, railroad magnates James and Louis Hill, and W.H. Cowles – the “ newspaper man and real estate holder of Spokane” whose family still merits the same description – had spent the intervening years finding other investors for the project and writing articles of incorporation for the development. The article reported on the anticipated groundbreaking and excavation of the hotel. It also reported that Pehrson was in Minneapolis “conferring with the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery company, which has the steel contract.”

In 1913, Pehrson’s obscurity was understandable. But today, Pehrson should really be a household name in Spokane. Unlike Cutter, whose best work is residential homes, Pehrson designed some of the most recognizable buildings in Spokane – work that arguably defines the city more than any Cutter structure.

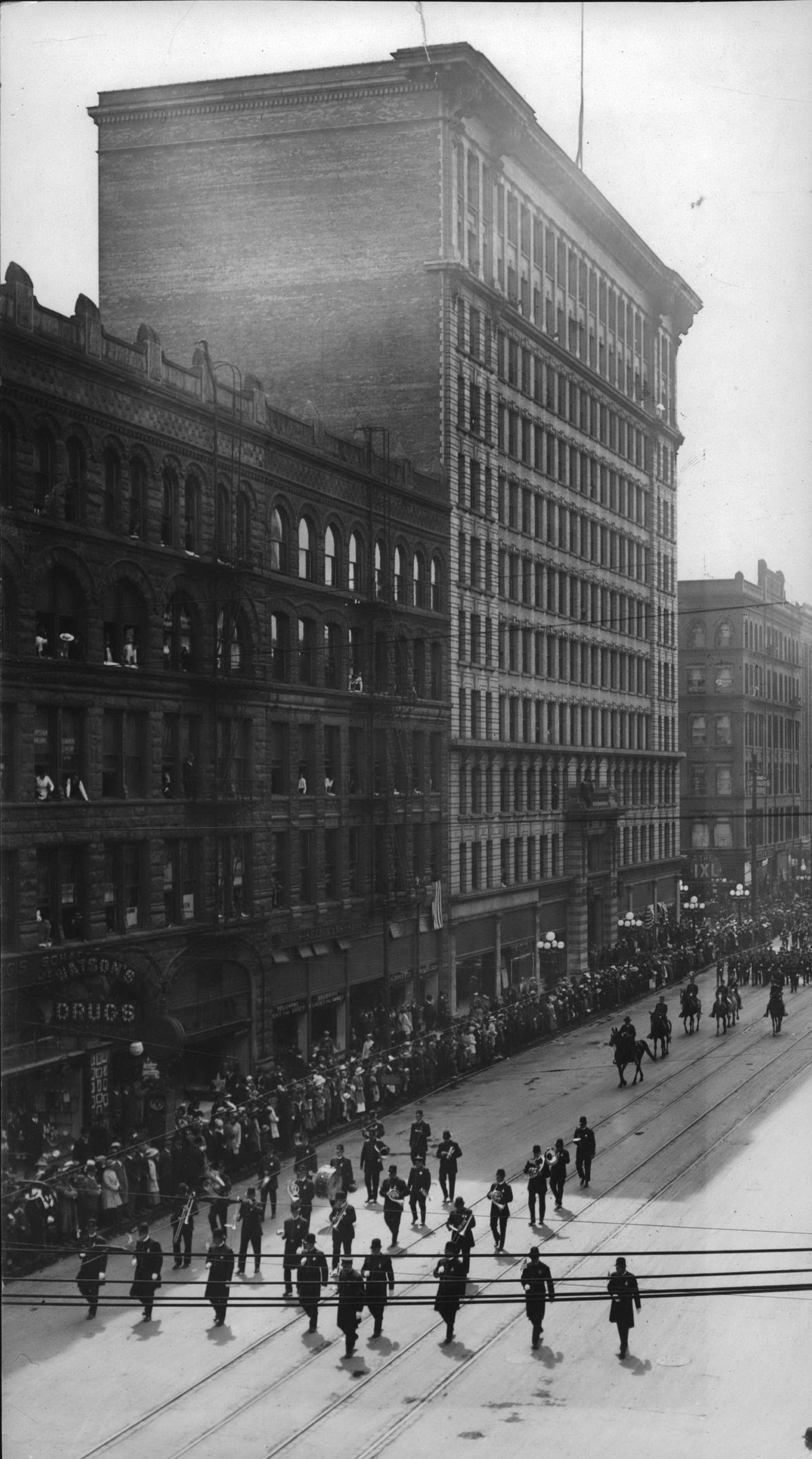

There’s the 15-story Paulsen Medical and Dental Building, which is “one of the most prominent features of the Spokane skyline,” according to the city’s Historic Preservation Office. The Spanish- and Moorish-inspired Art Deco building reigned as the city’s tallest for 50 years, and remains one of the most unique structures in the city.

1928 - An unidentified parade passes the Granite Block, left, and the Paulsen Building, center, on the 400 block of West Riverside Ave. in 1928. Both buildings represented Spokane’s boom era from 1890 to 1915. (Frank Palmer / SR)

There’s the Chronicle Building, a terra-cotta faced Gothic structure ringed with gargoyles – the “humble printer’s devil, without which no newspaper office, rustic or metropolitan, is complete,” as the paper wrote in 1928. And there’s the Chancery building, which housed the Catholic Diocese of Spokane for 53 years but is now vacant and under threat of demolition, according to preservation advocates.

Pehrson was also the architect behind the Eldridge Buick building at Cedar Street and Sprague Avenue that now houses the Rocket Bakery; the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church on North Washington Street; the Woman’s Club of Spokane building on West Ninth Avenue; the former Pay’n Takit building on East Sprague now home to Best Asian Market; the sentinel Centennial Flouring Mills on East Trent Avenue; and the downtown Rookery Building that was demolished in 2005 and 2006.

The four buildings making up the Rookery block were built following the Spokane Fire of Aug. 4, 1889 and opened in 1890. The buildings, located on the southeast corner of Riverside and Howard, are shown here in the 1920s. The United Cigar Store was located at the corner of the building. The buildings were razed in 1933 and the current Rookery Building was erected in 1934. (The Spokesman-Review photo archive / SR)

In 1913, Pehrson had no structures to his name – but his signature and initials are all over the hotel’s original blueprints as the Davenport project architect working for Cutter.

The hotel’s archives still hold the original blueprints for the hotel. On page after page – below the Cutter company logo – are the initials G.A.P. and the date, Jan. 7, 1913. His family’s archives have even more blueprints with Pehrson’s full signature, from May 1913.

“It’s interesting because most of the buildings he did, he gets direct credit” in contemporaneous news articles, Lawrence said of his grandfather. “When it comes to the historic Davenport, there just isn’t that credit. But there is a body of information that leads to it. His signature is everywhere, where the architect’s signature should be.”

Michael Houser, the architectural historian with the state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, warned against drawing conclusions from Pehrson’s initials and signatures, saying it was “very typical” for staff architects to sign off on plans even if they weren’t responsible for the overall design.

“That’s not uncommon,” Houser said. “The actual firm you’re working for gets credit. That happens a lot. They may have 25, 30 architects working for the firm. It could’ve been a really busy time in the office.”

Ron Wendle, a local architect who has renovated numerous historical structures, offers a different perspective. Cutter may have been the hotel’s architect of record, but a “close look” at the hotel’s original drawings show Pehrson’s “high level of involvement and responsibility throughout the project,” he said in a 2016 article in Nostalgia Magazine.

Out of Cutter’s shadow

Whatever Pehrson did, Davenport liked it.

It’s true that Davenport and Cutter had a special relationship. In 1909, Davenport had Cutter design his first house, on Spokane’s South Hill at 34 W. Eighth Ave. But it’s also true that after the Davenport opened in 1914, Davenport relied on Pehrson.

Pehrson and Cutter had cooled to each other, and Pehrson quit once the Davenport’s drawings were complete and headed to Chicago. Davenport, however, placed more belief in Pehrson and caught a train to Chicago, where he told Pehrson, “I’ll get you all the work you can use after you finish my hotel,” according to a 1993 research project by William Hottell at Gonzaga University.

From that point forward, Pehrson was Davenport’s architect.

Davenport turned to Pehrson in the early 1920s to build his country estate manor, Flowerfield, his 120-acre summer estate on the banks of the Little Spokane River that is now part of Saint George’s School.

By the late 1920s, Davenport sought to expand his hotel, and hired Pehrson for a large addition lengthening the east wing of the U-shaped building, which “became the dominant feature of the high-rise portion of the hotel,” according to the historic places nomination. Pehrson “continued with such alterations as were made until Louis Davenport relinquished his control” of the hotel in 1945. Those alterations included the Delicacy Shop in 1917, and the Pompeian Baths in 1923.

Davenport Hotel under construction first guests in 1913. (Eastern Washington Historical Society / Libby Collection)

In 1939, Davenport hired Pehrson to design another of one of his homes, this one in LaHabra Heights, California.

Perhaps the greatest proof of the bond the men shared, Pehrson listed Davenport as the “person who will always know your address” on his World War II draft registration.

Cutter had a different journey. In 1923, he left Spokane and moved to California, never to live again in the city that claims him as its own.

Houser, the state historian, said he didn’t doubt that Pehrson did most of the design work of the Davenport. Even so, Cutter shouldn’t be dismissed.

“It wouldn’t surprise me” if Pehrson designed the hotel, Houser said. “It’s pretty likely he did design it.”

Regardless, Cutter had hired and first paid Pehrson for whatever work he did on the hotel, and Cutter was in Spokane to shape it in its earliest days.

“He’s the guy that really shaped the early environment of Spokane,” Houser said. “Cutter was there for the big boom. He did a lot of structures that were tied to the wealthy mining and lumber barons that were there. Pehrson is younger, so maybe by that time they weren’t building the big mansions. There were other players in town. There were other architects working in the city.”

Houser said Pehrson “had quite a career” and acknowledged that Pehrson should be better recognized.

Part of that recognition could begin with the Davenport Hotel.

Matt Jensen, corporate director sales and marketing for the Davenport hotel group, said he’s only ever heard of Cutter’s involvement, but was interested in hearing more about Pehrson.

“Everything’s always pointed to Cutter,” Jensen said. “All we know is what we know, from what’s been presented. Sometimes this is what it takes. It takes family to come forward and say, ‘This is what really happened.’”

Lawrence said he’s ready to set the record straight and get Pehrson out of “Cutter’s shadow.”

“I’m not anti-Cutter. There are a lot of great buildings, and our city is what it is due to Cutter, architecturally,” he said. “I’m not going to say he had no role in the historic Davenport, but I’m not going to say he had all the involvement, either.”

The Davenport Hotel was built in 1914 and completely restored by developer Walt Worthy in 2002. (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo