French women demand action amid high domestic violence rate

LES MUREAUX, France – Sylvia. Dalila. Aminata. Celine. Julie. Their names are plastered on buildings and headlines across France, calling attention to their shared fate: Each was killed, allegedly by a current or former partner this year.

More than 130 women have died from domestic violence this year alone in France, according to activists who track the deaths.

European Union studies show France has a higher rate of domestic violence than most of its European peers. And frustrated activists have drawn national attention to a problem President Emmanuel Macron has called “France’s shame.”

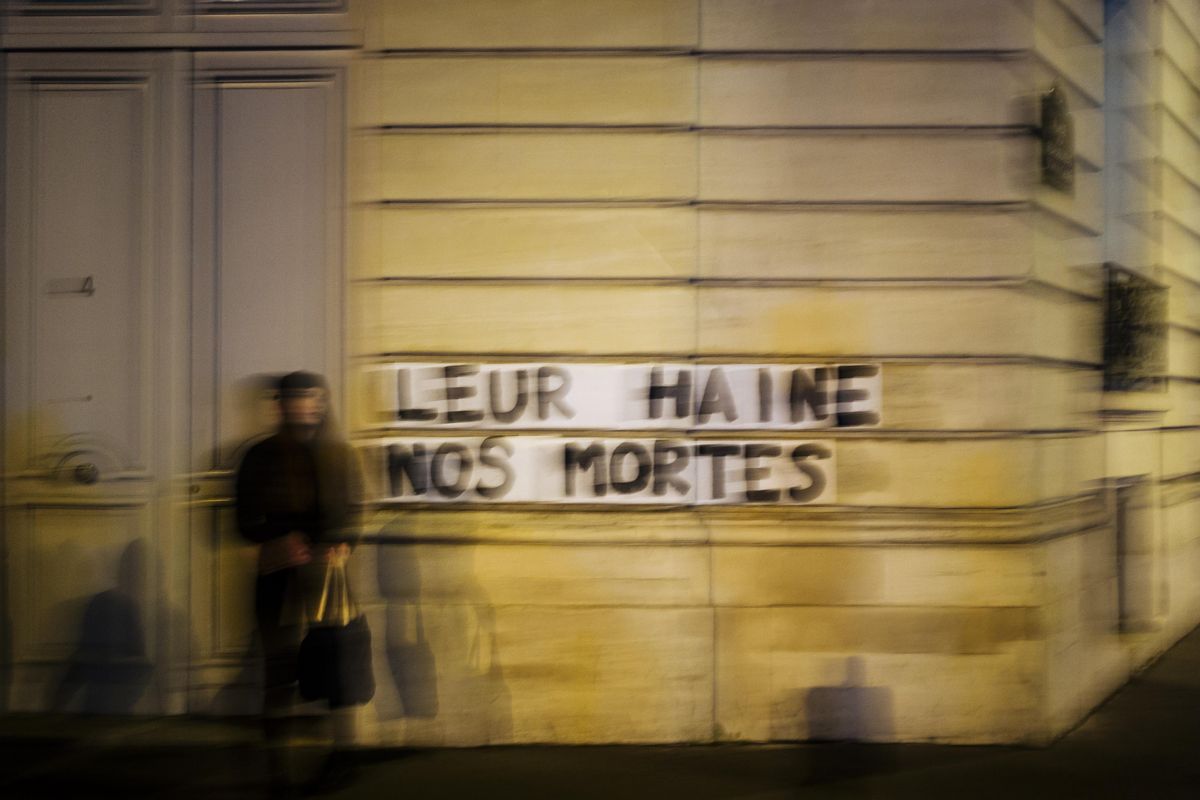

Under cover of night, activists have glued posters with the names of the dead and calls to action to French city walls. “Complaints ignored, women killed,” read the black block letters on one such sign. They have also posted anti-violence slogans, tagged with Macron’s name.

By the hundreds, women have walked silently through city streets after each new death.

Two years after Macron made a campaign pledge to tackle the problem, his centrist French government has begun to act.

A Justice Ministry report released earlier this month acknowledged authorities’ systematic failure to intervene to prevent domestic violence slayings. On Monday, the government will announce measures that are expected to include seizing firearms from people suspected of domestic violence, prioritizing police training and formally recognizing “psychological violence” as a form of domestic violence.

Women are not the only victims of domestic violence, but French officials say they make up the vast majority.

Lawyers and victims’ advocates say women are too often disbelieved or turned away by French law enforcement. But they’re encouraged by the new national conversation, which they say marks a departure from decades of denial.

“In France, we always have the impression that we are perfect,” activist Caroline de Haas told The Associated Press.

A 2014 EU survey of 42,000 women across all 28 member states found that 26% of French women respondents said they been abused by a partner since age 15, either physically or sexually.

That’s below the global average of 30%, according to UN Women. But it’s 4 percentage points above the EU average and the sixth highest among EU countries.

Half that number reported experiencing such abuse in Spain, which implemented a series of legal and educational measures in 2004 that slashed its domestic violence rates.

Conversations about domestic violence have also ratcheted up in neighboring Germany, where activists are demanding that the term “femicide“ be used to describe such killings.

In France, victims and advocates say government action is overdue – and that more training is needed for police who are often ill-prepared to protect women in danger.

Police inaction made national headlines in France after Macron visited a hotline call center in September and listened in on a call with a 57-year-old woman whose husband had threatened to kill her. He heard a police officer on the other end tell the woman he couldn’t help her.

The hotline operator told Macron that such responses weren’t unusual.

Police officers across Europe often dismiss domestic violence as a private matter and fail to intervene at crucial moments, an EU study found this year.

But France is particularly bad, said EU researcher Albin Dearing, who led a study this year that examined domestic violence in seven European countries, including France.

“When it comes to violence against women, it showed actually that police do very little to protect women who turn to them for protection,” he said.

It can take between three weeks and two months for authorities to act on a complaint, leaving the victim “in a very fragile situation,” according to Frederique Martz, who runs anti-domestic violence organization Women Safe.

The Justice Ministry report this month found that 41% of “conjugal homicide” victims studied had previously reported incidents of domestic violence, and 80% of complaints sent to prosecutors went uninvestigated.

“Our system doesn’t work to protect women,” Justice Minister Nicole Belloubet told French TV channel LCI after another French woman was allegedly killed by her husband in Alsace last week.

But Maj. Fabienne Boulard of the national police said many officers respond appropriately to reports of domestic violence. Those who don’t – the ones who react “clumsily” or ask the wrong questions – usually don’t mean harm, she added; they just don’t recognize domestic violence or know how to intervene.

This is particularly true when women receive threats but not yet physical blows, victims say.

Officers “absorb this violence into the category of violence between a couple that is going through a difficult period,” said one woman whose ex-husband repeatedly threatened her and their children. She spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation.

The woman divorced him after years of what she describes as psychological abuse that left her “terrified to cross him.” His threats only grew worse from there, she said.

She filed multiple complaints, but she said police officers suggested she didn’t seem like a victim or wasn’t able to prove that she was in danger.

Earlier this month, Boulard led the first supplementary training on domestic violence for police in the Paris suburb of Les Mureaux. She emphasized to the eight officers there that among victims, “shame is an extremely strong feeling.”

Participants traded stories of issues they had encountered: the surge in complaints on Sundays, the woman who retracts her complaint, the partner who insists everything is fine.

“We can’t do anything,” one female police officer complained.

Boulard told The AP that the three-hour session aimed to help officers understand the pressures that victims face and “why the victim is not what they imagined, why sometimes they don’t correspond with the criteria they expect to see.”

Trainings like Boulard’s take place in some parts of France, but regional authorities can decide whether to hold them. Activists hope they’ll become routine.

“A year or two ago, no one used the word `femicide’ apart from feminist organizations,” Haas said. “There is very much a change in public consciousness.”