Tracking antenna set up along Salmon, Lemhi rivers to spy on baby chinook

IDAHO FALLS – Elaborate riverbank antennas appeared this fall along the Salmon and Lemhi rivers as part of a study to learn where juvenile chinook salmon like to hang their hats before heading off to the ocean.

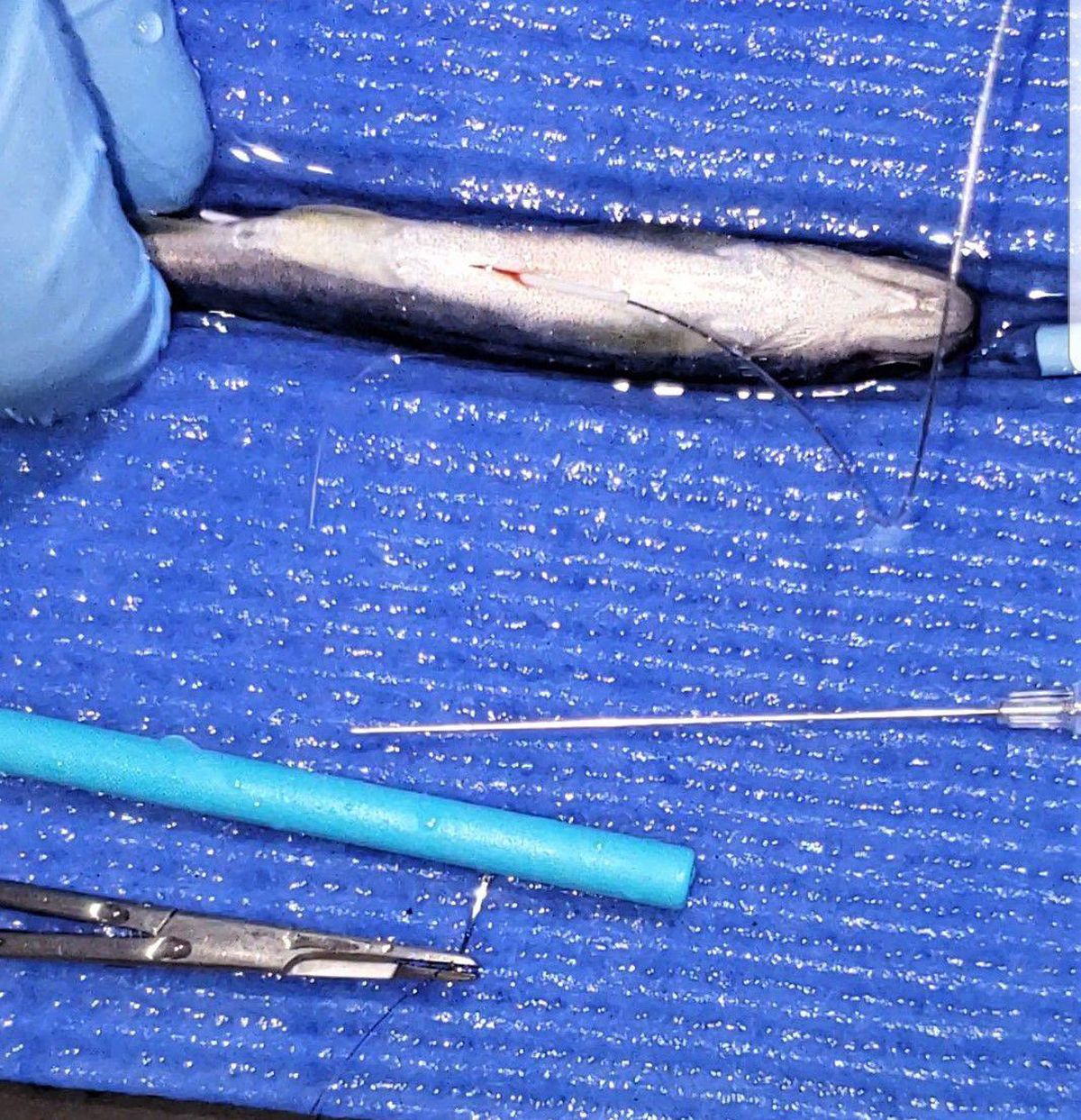

Like collaring grizzly bears or wolves only on a miniature scale, tiny radio tags the size of Tic Tacs are implanted into 4-inch-long pre-smolt fish so that biologists can track their movements and see what habitat appeals to them most.

The information will direct future efforts on habitat restoration in the two rivers.

“These are all wild fish,” said project director Nick Porter, with Biomark Applied Biological Services. “The overall goal for much of the salmon restoration is to try and have a self-sustaining population of just wild fish.”

Porter said finding out where the pre-smolt salmon prefer to live through the winter will help researchers know where and what kind of habitat to restore.

The project is being conducted by biologists from Biomark in cooperation with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Over the next several months, the antennas will track and record the radio-tagged fishes’ whereabouts 24 hours a day. Biomark has six antennas on the Lemhi River, six along the Salmon River from Salmon downstream to Corn Creek and one about 40 kilometers downstream from Corn Creek.

The tiny fish are surgically fitted with a radio tag weighing less than half a gram. A rotary screw trap operated by Fish and Game is used on the Lemhi River to catch the smolts. After the fitting, they are released back into the river and tracking begins.

“Ultimately, information collected in the study will help managers in future habitat restoration and conservation activities in the upper Salmon River basin,” Fish and Game fisheries technician Brent Beller said.

Mike Demick, of the Salmon Fish and Game office, said the department can use the information gathered by Biomark to focus on habitat improvement.

“We have a fairly large habitat improvement program, and we’re doing quite a bit of work on the Lemhi River, the North Fork and Pahsimeroi River,” he said. “We’re trying to improve especially the winter habitat so those little fish can stay in there. When it’s a channel, there’s not a lot of habitat.”

Demick said when flows on the Lemhi River drop significantly, such as in midwinter, they suspect the fish migrate out to better habitat in the Salmon River.

“Young salmon tend to like the tucked away pools and in habitat where water’s not moving fast and little side channels with debris and branches hanging down in the river,” he said. “Where they can feed actively and not swim, swim, swim all the time.”

Porter said from previous data collected, about 70 percent of the pre-smolts are leaving the Lemhi River and moving into the mainstem of the Salmon River.

“Radio tags have a range of about 200 meters on our fixed (antenna) sites and with our floating catarafts we can see about 100 feet on each side, so we can see the entire river,” Porter said. “We can see what sites they are actively selecting. We can get it down to a scale of a couple of meters. We can see if they like undercut banks or certain sizes of stones or substrate.”

Porter said having plenty of good habitat is a priority in the overall effort to restore chinook salmon in Idaho.

“If you invite 50 people over to your house, but you only have enough room for 20 people, that doesn’t make a lot of sense to me,” he said. “We want to have enough habitat for these chinook salmon when they do come back after that long 800-mile migration.”

Habitat improvement for salmon and steelhead is one of the measures being taken to stave off the disappearing fish in Idaho’s rivers. In the 1950s, about 1.5 million spring and summer chinook returned to the Snake River basin annually. In 2017, 5,800 spring-summer chinook returned. Wild steelhead numbers dropped from more than 100,000 in 1964, to about 15,500 in 2017. In 1992, one sockeye salmon returned from the Pacific Ocean to Redfish Lake in central Idaho.