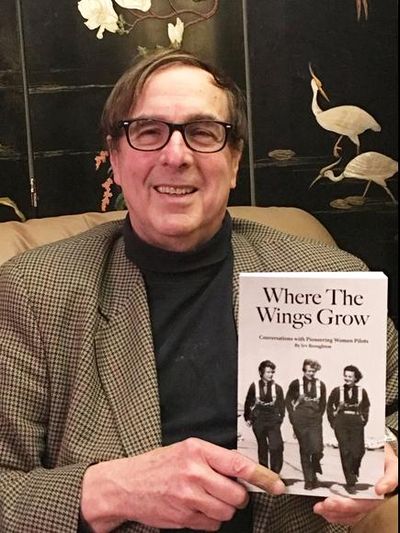

SFCC’s Broughton gives flight to female pilots’ stories with ‘Where the Wings Grow’

When he was a boy growing up on Cape Cod, Irv Broughton was fascinated by flying.

His family lived near what was Camp Wellfleet, a training facility and practice gunnery range for military pilots. He and his friends would scour the sand dunes, searching for pieces of the demolished target drones – especially the magnetos – that would float down in parachutes.

And whenever he could, he would seek out those who flew.

“There were a lot of interesting people there,” Broughton says. “And a lot of them were pilots.”

Years later, while studying for his graduate degree in creative writing, he would meet someone who would prove to be the inspiration for his 16th book, a collection of interviews titled “Where the Wings Grow: Conversations With Pioneering Women Pilots” (Open Look Books, 572 pages).

That someone was Ann Darr, a poet whose titles include “St. Ann’s Gut” and “The Myth of a Woman’s Fist.” Broughton reviewed “St. Ann’s Gut,” Darr liked what he wrote and the two struck up a friendship.

That friendship was cemented when Broughton discovered that, during World War II, Darr had been a WASP – a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots group. Darr and more than 1,000 other women became WASPs, federal civil service workers who flew and tested aircraft, ferried planes and trained other fliers.

“That sort of got me into the area of women pilots,” Broughton says. “She (Darr, who died in 2007) was just a bundle of life and good humor.”

Over the next 40 years, Broughton – who has taught at Spokane Falls Community College since 1976 – compiled 26 more interviews for his book.

Why did it take four decades to complete?

“(T)his one just took a long time to collate,” Broughton says. “I’d pick up an interview here and there. I’d do one, then go two years and do another and then three more years to do a third.”

He sought out his interview subjects in between pursuing his teaching career, publishing books in a range of disciplines (other interview compilations, poetry, short stories, plays and even a novel) and making a number of short films.

But he always came back to his women pilots. Why?

“I just think they’re fascinating,” he says. “These are remarkable women.”

Take Teresa James, who died in 2008. She was a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), an organization that preceded the WASP. Commissioned a major in the Air Force reserve in 1950, she was also the first WAFS pilot to ferry a military plane from coast to coast.

James’ story is particularly poignant because she received word that her husband’s B-17 had been shot down over France. For years she held hope that he had survived. It was only when she traveled to Europe in 1984 and talked to people who’d witnessed the crash that she knew for certain he was dead.

Or there’s Dorothy Hester Stenzel, who died in 1991. As a teenager, Stenzel, whom Broughton describes as “tough and crusty and fascinating and sweet,” earned the money to take flying lessons by, she told him, “doing parachute jumps for $100 a jump.” She later trained with famed barnstormer Tex Rankin and ended up running her own flight school in suburban Portland.

Of Stenzel, Broughton says, “Amelia Earhart was quoted as saying, ‘That girl can fly.’ ”

And, of course, there’s Darr, who spoke for many of the women when she addressed the prejudice they faced from their male counterparts.

“The male pilots – some of them – were not eager to have the women pilots around,” she told Broughton. “Some of them simply thought woman couldn’t do anything as well as a man. Some of them thought it was too dangerous a job for women. Mostly though, it was a matter of ego, I believe.”

Which, she added, was ironic. “As it turned out,” she told Broughton, “our record for flying was better than the men’s.”

It’s that kind of spirit that kept Broughton working on the book project, persevering despite the passing years and through one disastrous incident in which he lost a batch of original materials to a flooded basement.

But, as he says, “The candidness of these women is remarkable. They suffered a lot, many of them, but they were very sanguine. They weren’t self-pitying.”

Despite their war-time service, WASPs didn’t earn veteran’s status and the attendant benefits until 1977. In 2009, they were awarded a group Congressional Gold Medal.

“I think it’s fascinating the way they handled the adversity, with great grace,” Broughton says. “And I think it’s inspirational, for men or women, to learn about people who achieved greatness while operating under great restraints.”