Soaring through history: Women aviators have a rich story to tell in Washington state

Amelia Earhart, arguably one of the most famous female aviators, wasn’t the only female pilot storming the skies or air racing in open-cockpit airplanes back in the 1920s and ’30s.

Women have been flying airplanes almost since the Wright Brothers’ first 12-second flight in 1903. By 1930, there were about 200 women pilots in the U.S., and by 1935 there were 700 to 800 licensed women pilots, according to historians.

Jean Isabella Landa was born in Spokane in 1917 and grew up in Spokane Valley in the 1920s and ’30s. Landa, born to parents who, like most Americans at the time had an eighth-grade education, graduated from Central Valley High School at 16, and received her pilot’s license at Felts Field airport in Spokane. Like Landa, most women who learned to fly at that time got instruction through civil pilot training programs.

“She loved to fly,” said Carol Landa-McVicker, one of Landa’s four daughters who lives in Spokane. “I flew with her a few times, and when she was a up in the air you could tell she had that sense of freedom. She just loved it. Just being up above the clouds.”

When the U.S. entered World War II in the early 1940s, Jean Landa had already attended Stanford University, Whitman College in Walla Walla and graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in sociology – at a time when most women weren’t working outside of the home. After college, she worked as a flight instructor in the Pullman-Moscow area where she met her future husband, Carlos. The two married and Landa decided to apply to become a member of WASP – Women Airforce Service Pilots.

As Landa-McVicker pulls old newspaper clippings and various ephemera from a box, she continues to chat about her mother. “She was part of that tradition of strong women who wanted to make a difference,” Landa-McVicker said.

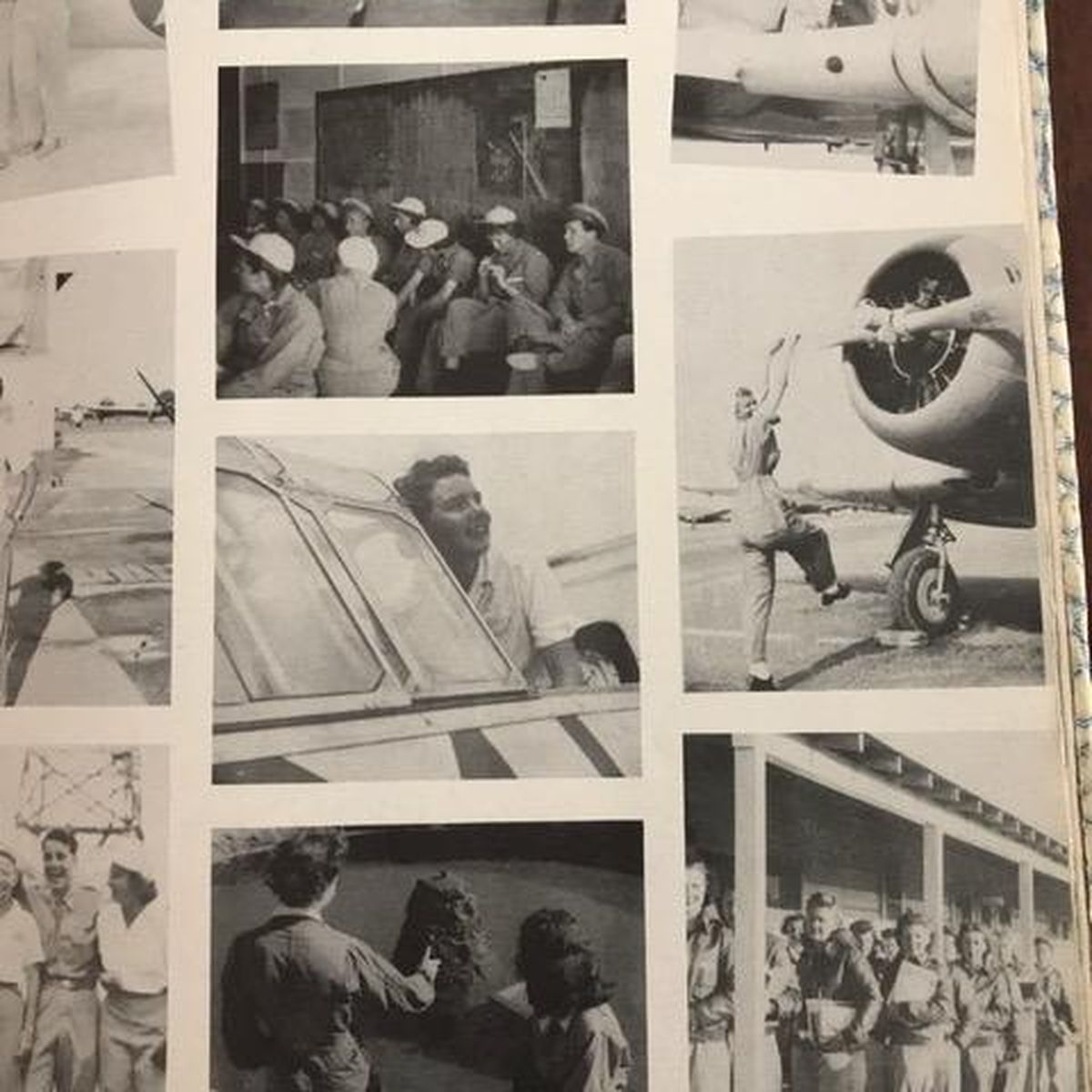

Carefully brushing the dust off the leather of a WWII bomber cap lined with fleece, she pulls out a bedraggled yearbook with a cobalt blue caricature of a woman with wings flying on its cover beside the designation 44-W-7, which represents Landa’s class in 1944 at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas.

WASP was established during World War II, combining the efforts of two famous female pilots at the time, Jackie Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love, who had proposed programs for women pilots.

The proposals were met with opposition as they bumped into beliefs that women were not suited to be pilots, but the opportunity to free male pilots for combat helped the case.

The effort was aided by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who in a quote from 1942, famously said: “This is not a time when women should be patient. We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.”

In order to apply for WASP, a woman had to have a civilian pilot’s license with a minimum of 200 hours in the air. And, because WASP members were U.S. federal civil service employees and did not qualify for military benefits, each member paid for her own transportation costs to training sites, their uniforms and room and board.

Landa, as one of 1,830 accepted from the 25,000 applicants, is a member of a small sisterhood: women who have served as military aviators. Landa and the other women pilots were trailblazers, a group of 1,102 female civilians who flew military aircraft under the direction of the United States Army Air Forces.

While the WASP were not trained for combat, instruction was essentially the same as male aviation cadets. Trainees received no gunnery training and very little formation and aerobatic flying, but went through the maneuvers necessary to be able to recover from any position.

By graduation, WASP recruits had 560 hours of ground school and another 210 hours of flight training. They knew Morse code, meteorology, military law, physics, aircraft mechanics, navigation and other subjects.

WASP pilots flew 78 different types of aircraft, from the smallest trainers to the fastest fighters and the largest bombers. They flew more than 60 million miles, and put in 300,000 flight hours. Thirty-eight gave their lives in the service of their country – five from Washington state.

Landa-McVicker said there wasn’t any value seen in a women attending college in her mother’s day, “they were just going to go home and raise children after all,” she said. Although she didn’t talk about it all the time, she said her mother was proud of being a WASP.

“She talked about her time in the WASP, and like so many of us she would do things, and then later would say that was pretty amazing,” she said. “She mostly talked about her friendships with the other women.”

The WASP had safety records comparable and sometimes superior to their male counterparts, and many expected the program to morph into a branch of the Army Air Corps. But by the end of 1944, two years after its inception, it was canceled.

At the time, historians say people felt like the war was winding down, and that the women were no longer needed.

Like the Rosie Riveters who ironically worked on the planes they flew, WASP women returned to normal life after the war. There was no “thanks” from the U.S. government, they were just basically sent home.

By 1945, Jean Landa already had one child and would return to Spokane Valley with her husband, Carlos, to have four more children and establish a career in the banking industry. In hindsight, Landa-McVicker said her mother led by example but in those days, her mother was unusual in her Valley neighborhood.

“Even the fact that my mom worked was unusual,” she said. “So she wasn’t the Girl Scout or Campfire Girls leader. She was so supportive of us and we had lots of opportunities. She always said, ‘You can be anything you want.’ ”

After World War II

By 1944, media support and public opinion were turning away from all-out war efforts and focused instead on efforts to return America to an idealized prewar style of living. At the time, it was assumed the war was won and interest focused on the postwar economy, particularly in jobs for returning servicemen. At war factories, women were being laid off in record numbers, and popular media, movies and books advocated the return of women to their “rightful places” in support of men.

Many female pilots wanted to continue flying commercially, which was unheard of at the time, and with the large numbers of male pilots at the end of the war, few women were able to locate such positions.

Landa continued to fly with the Civil Air Patrol and started a career that would see her launch a Spokane Valley-based savings and loan association with family members, which later merged to become Pacific First Federal Savings & Loan. She also was an early entrepreneur who put banking in a grocery stores (Rosauers). Additionally, Landa was treasurer of Opportunity Township for several years and was named vice president of the Spokane Valley Chamber of Commerce. She also was a member of the Women’s Symphony Society, on the YWCA board of directors, League of Women Voters, several college alumni groups, and supported Spokane Civic Theatre and the Northwest Indian Center, her daughter said.

“She was ahead of her time,” her daughter said. “Many of the WASPs went back to being housewives but my mother was never satisfied with being a housewife. She never was. She was very nontraditional, and ahead of her time. Especially at a time when she and other women didn’t have access to borrowing money or even owning property.”

Other than the reunions held by the women who flew for WASP, their contribution was quickly forgotten until the 1970s when efforts by the women to achieve due recognition succeeded. The women spoke of being denied military benefits and assistance for burial, and of not receiving the educational benefits afforded other war veterans, not to mention the respect, according to historical accounts.

In 1977, women pilots were granted veteran status by President Jimmy Carter. And in March 2009, President Barack Obama signed legislation honoring the women’s wartime success by awarding all with the Congressional Gold Medal. The 38 killed in training or on duty received the award posthumously. At the time of the awards, approximately 300 Women Airforce Service Pilots were alive, 12 of them living in Washington, according to a state historian.

Landa-McVicker made the trip to Washington, D.C., in 2009, with several family members to receive the coveted Congressional Gold Medal.

Over the years since World War II, many more barriers for women pilots have been brought down, and records continue to be broken. Jackie Cochran went on to be the first woman pilot to break the sound barrier, with Chuck Yeager acting as her chase pilot, on May 20, 1953. In 1953, Marion Hart flew the Atlantic at the age of 61.

In the 1970s, the military dropped the prohibition on women flying in combat missions. In 1995, Martha McSally became the first female fighter pilot to fly in combat, flying an A-10 Thunderbolt II on a mission in Iraq.