Syrian goalie was an extremist to some and a cautionary tale to others

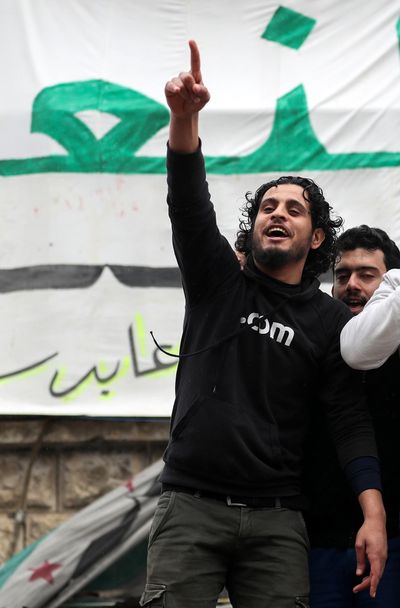

BEIRUT – He was a teenage goalie on Syria’s national soccer team who gave up his athletic career to join the 2011 protests against Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government.

His voice, heard in passionate paeans to the uprisings sweeping the country, earned him the nickname the Nightingale of the Revolution.

By the time Abdul Baset al-Sarout succumbed Saturday at age 27 to wounds sustained in battles in northwestern Syria, he had become a rebel commander, a revolutionary icon willing to work with anyone to destroy a government he despised. He had aimed to reverse the slow-motion defeat of the opposition under whose banner he fought and died.

Al-Sarout had also lost four brothers and several cousins and uncles in the fight against Assad, while surviving several assassination attempts. The war years had transformed him from a chanteur leading nonviolent Arab Spring-inspired rallies to a desperate fighter.

Abandoned by former allies in Syria and abroad, he was willing to give up all the idealism of the uprising and cast his lot with the veteran fighters of al-Qaida and Islamic State to continue the fight. His death, defending against a no-holds-barred Syrian army onslaught on the rebels’ last bastion in the northwestern cities of Idlib and Hama, has spurred debate over his legacy and what it represents.

“His voice lit the holy path for us,” Lina Shamy, a prominent opposition activist, tweeted over the weekend. “He warned us (not) to let down our Syria in his life and in his death.”

Some people condemned him as an extremist who called for a sectarian bloodbath, and said that the revolution was an Islamist conspiracy from the start. Others saw in him an example of what went wrong with the uprisings, that he had been tainted by radicalization.

Many observers consider al-Sarout’s beginnings in the uprisings as his finest hour.

Born in Bayada, a neighborhood in the city of Homs, al-Sarout was a top goalkeeper on Syria’s national team. Some say he was the second-best goalie on the Asian continent. But when the protests swelled all over Syria in March 2011, he supported calls for Assad to leave the presidency.

The first slogan al-Sarout ever chanted, according to an interview with a Syrian opposition journalist in Turkey in 2016, occurred as he gestured to his body and stared at troops deployed to quell demonstrations near Homs’ historic clock tower.

“Listen O sniper, here’s the neck and here’s the head,” al-Sarout said.

Al-Sarout was quickly expelled from the national team. He gained prominence leading protests as a charismatic singer in Homs.

A Sunni Muslim, he appeared with Fadwa Suleiman, a famous actress from Assad’s Alawite minority sect, to show, he later said, the “revolution is peaceful and pluralistic, not a revolution limited to a particular group.”

His songs too were nationalist, a soundtrack to the almost-romantic early days of the Arab Spring; “Heaven, heaven, our country is heaven, O my beloved homeland, you of the perfumed earth, even your hell is heaven,” went one chant.

Then came the government crackdown.

By December 2011, Homs’ streets had turned into sites of battles pitting government troops and local supporters against demonstrators; death tolls skyrocketed, people fled by the tens of thousands while others armed themselves in response.

“Till when will we stay like this? The people need international protection, a no-fly zone, military intervention, anything to protect these people from death,” al-Sarout said in an interview with an opposition activist that month after being shot in the leg when returning from a demonstration.

In the coming months, he, too, would bear arms.

“We came out with olive branches and bare chests. But when the whole world lets you down,” he said in the 2016 interview, “when you show demonstrations, strikes, with no racism or sectarianism, and you’re fought, then you have no choice but to take up the weapon.”

He said those who helped him organize protests became members of the rebel group he formed in Bayada. It was, in principle, part of the Free Syrian Army, an umbrella organization meant to organize and funnel materiel to armed brigades sprouting across the country.

But the Free Syrian Army was always more a concept than an actual entity; each rebel faction had its own sponsor to which it was beholden. And the Free Syrian Army, led by army defectors mostly based outside Syria, had few operational links with fighters such as al-Sarout.

The rebels’ disunity made Western support skittish. Meanwhile, Islamist groups, including then-al-Qaida affiliate Al Nusra Front, flush with money from Persian Gulf nations, proved to be the most disciplined and effective factions against Assad. (Al Nusra has grown to become Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. It’s classified as a terrorist group by the U.S. and is the strongest group in Idlib.)

The government, with support from Iranian-trained paramilitaries from Lebanon and Iraq, pummeled the rebels back to a few neighborhoods in Homs’ Old City Quarter. It surrounded the opposition enclave, employing the starve-or-surrender playbook it would call upon in later confrontations.

Al-Sarout repeatedly fought to break the blockade. Failing to do so from within, he went to Homs’ countryside to rally an offensive and bust the siege from the outside. He failed again, smuggling himself back in the beginning of 2013 to the besieged enclave to fight alongside his comrades, a journey featured in an award-winning documentary, “Return to Homs.”

They held out for more than a year in what had become a wasteland of rubble and rusted rebar, subsisting on whatever leaves and weeds they could find, according to various sources.

The opposition outside the rebels’ enclave in Homs, along with various other nations, vowed to help. Then, in May 2014, a cease-fire deal bused fighters unwilling to accept government control out of the enclave to then opposition-held areas outside Homs.

By then, all of al-Sarout’s brothers had been killed. Embittered by what he saw as abandonment, he gave an interview to an opposition outlet before leaving Homs. Gone were his compliments about the Free Syrian Army, which he dismissed as hopeless. Also gone was any mention of secularism.

Instead, he directed his comments toward Abu Mohammed Jolani and Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi, the respective leaders of Al Nusra Front and Islamic State, the only forces he thought strong enough to take on the government.

“They are Muslims just as we are, just as their goal is to empower Allah’s law on earth, so is ours,” he said, adding that it hurt to see his neighborhood taken by Alawites, Christians and Shiites.

“We’re not Christians nor Shiites to be afraid of suicide belts and car bombs,” he said, referring to the extremists’ tactics. “This is a message to the Islamic State, and our brothers in Al Nusra, that all of us are one hand to fight the Christians and take back the lands defiled by the regime.”

It was not to be. By that point, Islamic State had run afoul of other rebels and was fighting all sides. When news came months later that al-Sarout had pledged his allegiance to al-Baghdadi, Al Nusra fighters came to arrest him.

He escaped to Turkey, but surrendered in 2017 to an Islamic court in Idlib. He was acquitted, claiming he indeed wanted to work with Islamic State, but stopped when he realized the Islamist militant group was more concerned with establishing a caliphate than vanquishing the government. He was not with the Islamist militants, but he would not fight them either.

In 2018, al-Sarout joined with his brigade the Army of Glory, a Western-backed rebel faction operating in north Hama. That was where he was wounded last June 7, according to commanders in the group. He died a day later, on Saturday, and was buried Sunday, with hundreds attending his funeral in the northwestern village of Dana.

Eulogies poured in. Many said he was an inspiration and explained his turn as a natural consequence of fighting a government accused of deploying all manners of violence – airstrikes, indiscriminate as well as banned weapons, sieges, torture, all killing hundreds of thousands in the process – against those seeking change.

“All those things have been projected on Sarout, making his personal story into a sort of microcosm of the Syrian war and of the way it’s also been a war over how to reimagine an incredibly murky and fluid reality as something clear-cut and political,” Aron Lund, a Syria expert at the Century Foundation think tank, said in an interview via social media.

“To me, that’s maybe the most symbolic thing of all, because that’s been the story of Syria’s opposition all along. It was never a cohesive, unitary movement, and it meant so many different things to different people.”