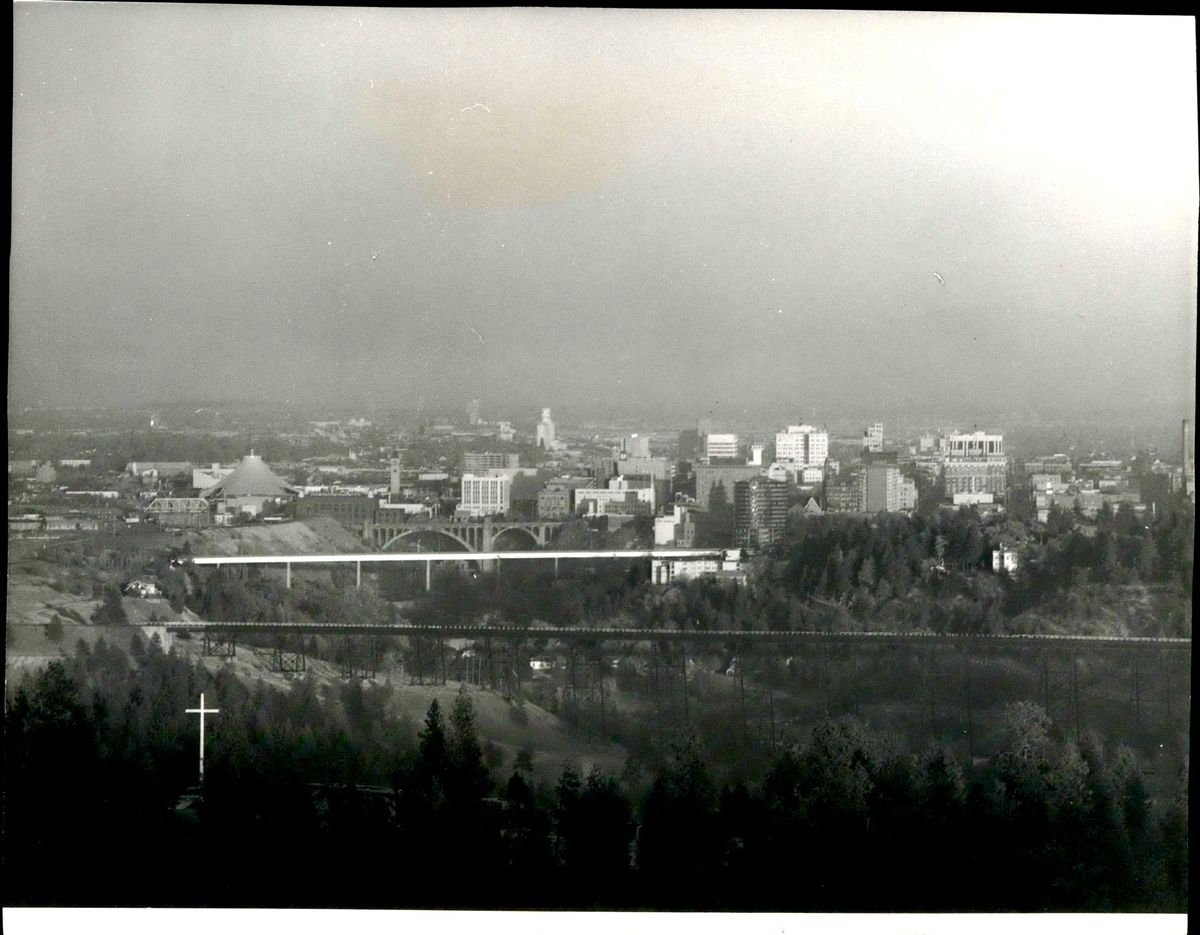

Before clean air agency formed 50 years ago, Spokane’s air was unhealthy more than a third of the time

One constant most employees at the Spokane Regional Clean Air Agency remember over the years is smoke and soot.

Mabel Mcinerney, a former interim director, secretary and inspector at the Clean Air Agency, said when the agency was founded in 1969, families were shaking soot out of their linens when taking them off the clothesline, and depending on the day, particulates from sawmills, garbage burning and coal stoves filled the air.

She said families across Spokane County would call and complain about the air. Most seemed to want a healthier lifestyle, as clean air legislation and pollution regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency went into effect.

Mcinerney, who worked for the Clean Air Agency for 30 years, was one of its first two employees and remembers being threatened, having rocks thrown at her car and being held at gunpoint when she was investigating air quality issues like garbage fires or field burning in the 1970s.

She said the early days of the agency were sometimes unpredictable, but air quality – and community relations – improved with time. Even the landowners who threatened her usually put out their fires after she left.

“They really were very cooperative, but things got kind of exciting there at first,” she said.

Fifty years after the agency’s founding, Mcinerney said its efforts to change Spokane County’s culture have paid off: “You always hope you made a difference.”

The agency has grown to 20 employees, and most of the year Spokane’s air quality is healthy. Since its early days, common practices like field and garbage burning have also been dramatically reduced.

Doug Pottratz, who also worked at the Clean Air Agency in the 1970s and is now a member of the advisory council, said one of the biggest challenges was changing Spokane’s culture. While Pottratz never had a gun pointed at him, he said he was once punched in the face while out in the field.

He said several demolition companies tasked with cleaning up what is now Riverfront Park for Expo ’74 didn’t always keep the required firefighting equipment on site. When Pottratz went to a fire in the park, which was filled with railroad ties at the time, he tried to take a photo of the fire with his Polaroid camera. While he was taking a photo, he said the owner of a demolition company punched him.

He said his only injuries from that incident were his pride and his nose.

Pottratz said one common practice inspectors worked hard to change was illegal burning. He saw people burn TVs, tires, furniture, yard waste, roofing and building materials. Sometimes people who were burning large piles of garbage would argue they were starting a cooking fire, but Pottratz couldn’t recall ever seeing any food.

Current and past agency leaders and employees celebrated its 50-year anniversary by planting a Kentucky coffeetree at the edge of Riverfront Park last week. Julie Oliver, the Clean Air Agency’s current director, said clean air inspectors aren’t usually threatened with guns or assaulted when they go in the field these days, but sometimes people are still resistant about reducing pollution.

She said many people try to burn things that are illegal, like tires, but most modern smoke issues that lead to poor air quality are caused by wildfires.

“The best we do with wildfire smoke is inform people,” she said.

She said the agency is also working on identifying other sources from vehicles, or industry, that could lead to poor air quality.

Tom Brattebo, a member of the Spokane Regional Clean Air Agency Board, said the agency’s work is more important than ever, because industries aren’t likely to hold themselves to clean air standards if no one is watching.

Brattebo, a Kaiser Aluminum manager for about 25 years, said being on the agency’s board was a way to atone for the pollution he helped caused during his career.

“I was guilty, and this is my repentance,” he said.

A former Air Force pilot, Brattebo said he has flown through cities with visible smog. He’s glad Spokane no longer looks that way.

For most of his career, he oversaw the aluminum smelters, which poured smoke into the air on a daily basis. He said air inspectors monitoring how smoky the plant was becoming pushed him to try to do what he could to reduce the amount of smoke it produced. He said the technology available at the time, however, would cause pollution no matter what.

After decades of technological advancement, companies have more ways to reduce pollution, Brattebo said, but they still need oversight from organizations like the Clean Air Agency to ensure they keep following the rules.

“If you don’t watch them, they’ll come back,” he said.