Reading the Northwest: Peter Heller’s ‘The River’ carries the reader on a swift current of adventure

It’s no surprise that author Peter Heller cites Ernest Hemingway as one of his earliest influences. The rhythmic voice and lyrical tone of Heller’s new novel “The River” bring Hemingway immediately to mind, as does the author’s theme of young men facing down danger in a rugged wilderness setting.

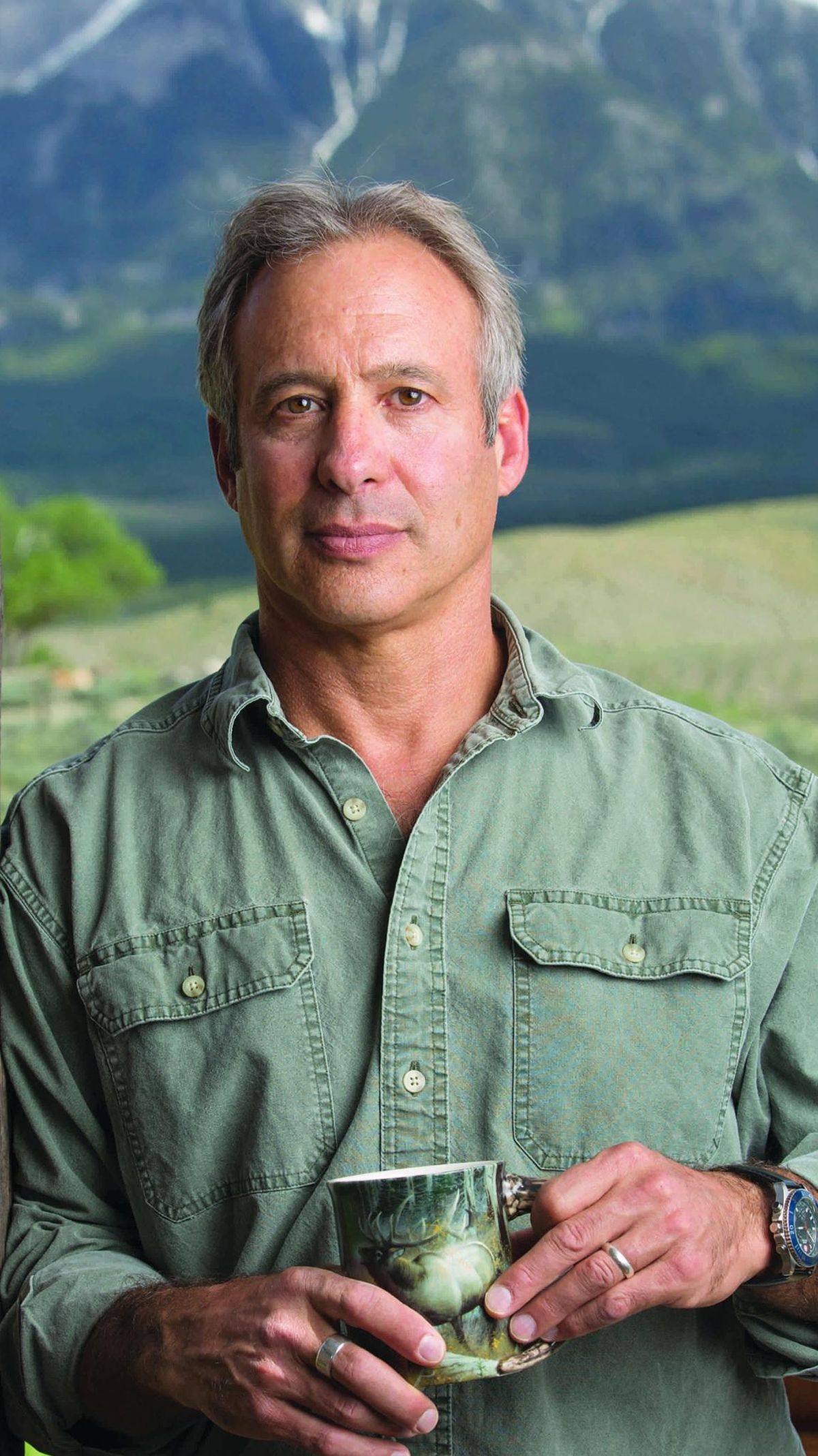

Heller is a manly writer who describes fly fishing with the eye of a poet but lets it be known that he always carries a Glock in his own fishing vest, just in case of bear, cougar or drunken “bowhunters from Arkansas.”

In “The River,” Jack and Wynn, best friends taking time off from Dartmouth, find their lives in peril as they paddle north toward Hudson Bay, with a forest fire bearing down on them. And there is more danger ahead once they rescue a badly injured woman and realize her husband may be lying in wait downriver, not to mention two drunken Texans, potentially deadly rapids, and mandatory portages around falls with names like Godawful and Last Chance.

Heller writes from experience, having paddled many treacherous rivers and chronicled dangerous and even deadly expeditions in a notable career as a writer for magazines such as Outside, Men’s Journal and National Geographic Adventure. The novel’s setting is closely based on the Winisk River in northern Ontario, which Heller ran years ago on assignment for a magazine.

Jack and Wynn meet on a freshman orientation hike at Dartmouth, just as Heller met his own best friend decades ago. Wynn, an artist and gentle giant, is based on Heller’s friend. The more hard-nosed Jack is “a tough ranch kid – he’s way tougher than me,” Heller said. “But I am like Jack in that we look at the world in a similar way.”

That means no illusions. Jack suspects the husband from the start, while Wynn is willing to entertain other possibilities, perhaps a bear attack. The injured woman, Maia, conveniently is unable to speak for several days, leaving the two friends – and the reader – waiting to figure out exactly what happened to her.

The dangers proliferate as the nights grow chillier and the river tumbles downstream toward the bay. The ride is thrilling, and so are Heller’s lyrical descriptions of the river and the business of paddling, informed by his many expeditions over the years. Heller makes the river come alive with its narrowing cataracts and tannic side creeks where the young men cast their rods, catching brook trout. He is meticulous in describing the gear they carry – the barrels of food and provisions, fishing rods and flies, knives, tent, sleeping bags and sweaters, all of which will be critical to their survival.

The writing shines when Heller describes the fire, approaching with not just a roar but “turbines and the sudden shear of a strafing plane, a thousand thumping hooves in a cavalcade, the clamor and thud of shields clashing, the swelling applause of multitudes drowned out as if by gusts of rain.”

Heller said his fire scenes were informed partly by his own encounter with the 1994 Storm King Mountain fire in Colorado that killed 14 wildland firefighters and burned more than 2,000 acres. “I was writing a long narrative poem,” he said, launching into the story, “and I finished work and I went outside to take a drink of water.” That’s when he saw the fire, approaching a neighbor’s house. Soon he was working alongside volunteers with a shovel and chain saw, and the fire blew up.

“There was a big gust, and the wall of smoke turned into jets of flame,” he said. “I heard the trees exploding, and you could see the flames shooting up, and the firemen said, “We’re out of here.” They escaped down the road, and within 90 seconds, the entire hillside burned, he said. “It made a deep impression on me.”

Heller, who now lives in Denver, has published four novels since launching his fiction career in 2012, including “The Painter” and “The Dog Stars.” He said the germ of his new book was planted at a spaghetti dinner in New Hampshire when he was 17, where he met a man who had just lost his wife on a river expedition in circumstances that were murky and unexplained. “And I walked away from that conversation, and I knew he was lying. My antennae were just humming – I was dead sure,” he said. “And I must have been thinking about it for 40 years because I started with the language of those first lines and then within a few pages I bumped up against that story.”

That’s right, he bumped into the story, because Heller said he doesn’t plan out his fiction but rather starts with the first line and lets the words flow, describing a process that sounds almost automatic but is certainly much more difficult than he makes it seem.

“When I sit down to write a novel, I want it to be like running a river for the first time,” he said. “You get in the current, you travel into territories that you’ve never been before. … You don’t know what’s going to be around the next corner. I love that about writing fiction.”

“The River” is not flawless, but it’s a rip-roaring good read, and surprises are definitely in store as the reader is carried along on a swift-moving, slender novel of adventure.

Martin Wolk is a writer and editor who enjoys reading contemporary fiction and memoirs. He has been a correspondent for Reuters and msnbc.com, among other publications. He writes The Spokesman-Review’s recurring “Reading the Northwest” column.