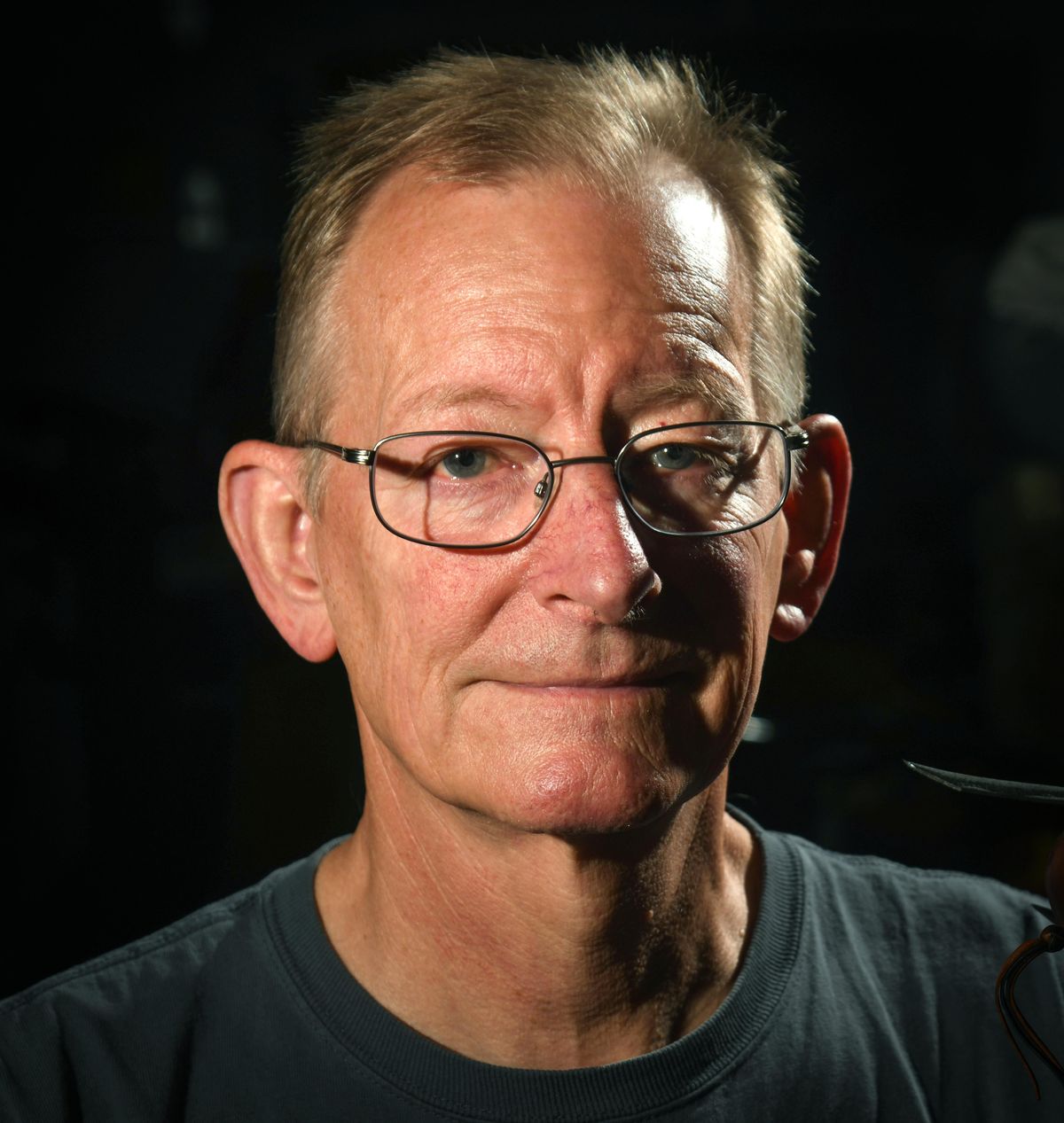

Front & Center: Demand, reputation means Spokane falconry hood maker doesn’t have to hawk his wares

Is it possible to be a celebrity yet also virtually unknown?

Doug Pineo has been honing his craft for more than half a century – “long enough that I have name recognition like Gucci,” he observes.

But that recognition is confined to a small, albeit growing, group: falconers.

“When I started, there were maybe 400 or 500 licensed falconers in the U.S. Now there are about 6,000,” he estimated. “There’s probably another 1,000 in Canada and a similar number in Mexico.”

Pineo’s pièce de résistance is his custom, hand-sewn, calfskin hoods, which go for about $150. He also sells gloves, gauntlets, vests and other gear.

“In the world of cocker spaniel and springer spaniel field trials, ours is the vest everybody wants,” he says.

During a recent Interview, Pineo (pronounced PIN-ee-oh) discussed his first encounter with a hawk, the art of making hoods and why people collect them.

S-R: Where did you grow up?

Pineo: I grew up in the Marine Corps. If your dad is in Marine aviation, you’re typically going to be on the Eastern Seaboard or Southern California. We also lived in England three years when my dad was attached to the embassy.

S-R: How many different schools did you attend before college?

Pineo: I think it was 6.

S-R: What interested you growing up?

Pineo: I was always fascinated by nature. I started fishing very early. When I was 8, I would tie flies with pins from my mom’s sewing basket and feathers I teased out of my pillow.

S-R: When did you first notice hawks?

Pineo: The family lore is that while we were visiting friends when I was 5, an immature red-tailed hawk tried to grab a chicken in their barnyard. Apparently, that made a big impression on me. In eighth grade I wrote a term paper on birds of prey and did all the watercolor paintings, copying Don Eckelberry’s artwork from a book about North American raptors.

S-R: When did you get your first bird?

Pineo: In 1964, when we were living at Mitchell Field, a deactivated Air Force base in Long Island. I trapped a kestrel and flew her about 10 days later.

S-R: And she came back?

Pineo: Oh, yeah, because she was hungry and there was food on my fist.

S-R: How long did you keep her?

Pineo: I flew her for six or seven months, then let her go. Later I had a red-tailed hawk that flew off on its own. You do lose them. We use telemetry now, but birds still go missing.

S-R: Why did you start making falconry equipment?

Pineo: Because you couldn’t buy it. I started when I was 13 or 14, and printed my first price list in ’68 after I graduated from high school.

S-R: Did you aspire to a particular career back then?

Pineo: I wanted to be a biologist. I went to Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. After graduation, I headed to the Bay Area, which has a rich tradition of falconry, and moved in with a group of crazy, obsessed falconers in San Jose, taking various odd jobs just so I could fly birds.

S-R: Then what?

Pineo: I moved back to Elmira, New York, where my mom was raised, and helped get falconry legalized in the state after the federal regulations were adopted in 1976. But there was not a lot of quarry. My dad was born and raised in Seattle, and I remembered an article by Les Boyd in the April 1967 Hawk Chalk, the newsletter of the North American Falconers Association, about hunting Hungarian partridge with a prairie falcon. That had me riveted. So in December of ’76 I drove to my grandmother’s house near Tacoma and plugged into Washington’s falconry community. Soon after, I got a job in the then-Washington Game Department’s Spokane office.

S-R: How long were you here?

Pineo: One year. Then I transferred to the agency’s headquarters in Olympia, where I met Trish, got married, and our daughter, Helen, was born. Three years later, when the recession hit and funding ran out for my job at the state Parks and Recreation Commission, where I’d transferred, I applied for a fellowship in the (fledgling WSU-UI) Institute for Resource Management and was accepted. After completing classwork and my research in 1984, I went to Boise and helped build the World Center for Birds of Prey. Then we moved back to Olympia, where I worked for the Washington Forest Protection Association, a lobby group trying to drag the timber industry out of the 19th century and into the modern world of wildlife management. A year later, I joined the Department of Ecology, and from ’85 until 2010 helped implement the state’s role in the Shoreline Management Act.

S-R: During those years in public service, did you continue growing your business?

Pineo: I made hoods for people throughout the ’70s and ’80s and ’90s – extra income that paid for my toys and helped the family.

S-R: Why do falconers use hoods?

Pineo: The hood allows you to carry a bird in chaotic surroundings.

S-R: Does the hood bother the bird?

Pineo: No, that’s the whole point. It helps them stay calm. The relationship between you and the bird can be defined by how well you make the bird to the hood. You don’t break a bird to the hood. You make it to the hood. That’s a significant semantic difference. The hood must fit the bird comfortably, or they won’t tolerate it.

S-R: Describe hood making.

Pineo: It’s sort of a cross between cobbling and fly-tying, and takes between three and five hours, depending on whether it’s bonded or hand-sewn. Hoods need to be lightweight and durable. And pretty. The pretty part is why people collect them.

S-R: Do your international clients each have their own ideas of what’s pretty?

Pineo: Yes and no. I have customers in the UAE (United Arab Emirates) who want the same hoods my European and North American customers want. But people’s tastes vary, whether you’re talking cars or shoes. I don’t make whatever hood I’m asked to make. I make a hood within the range of what I’m willing to do. And I’ve done this long enough that I have a reputation. The nearest analogy would be a really nice pair of cowboy boots, where the maker has a distinctive style and narrative. Same with hoods. Stories appeal to people.

S-R: If someone orders one today, how long until they get it?

Pineo: We used to be a couple of years out. Now that I’m retired, we’ve gotten much better – usually a month or less. I have an associate here in town who helps make the shells. He worked at White’s Boots for 15 years and is a wonderful craftsman. But I finish all the hoods myself.

S-R: How much are they?

Pineo: Most range from $115 to $170. We’ve sold fancier ones for $200.

S-R: How do you know what size to make?

Pineo: I ask the species and gender of the bird, and its flying weight. I get it right about 98 percent of the time. And if it’s too big or too small, no one ever wants their money back. They just keep it and ask me to make them another, because they know I’m 69. (laugh)

S-R: Where do you get your leather?

Pineo: From a New York tannery run by an environmental engineer who took over the family business. Leather used to be a commodity but now has become a premium material.

S-R: Did your formal education include any business classes?

Pineo: No, which is a great shame. But I’ve had mentors who’ve helped me with pricing, because I tend to underprice my products.

S-R: How has your business evolved?

Pineo: The internet has made a huge difference. We used to be primarily mail-order. I’d also go to meets and sell things, which was a good cash bump. Now we sell almost exclusively online. Another change is I don’t stand in line at the post office anymore. We have a fulfillment center we work with. But I still go to meets for the fellowship because I’m a falconer first and a vendor a distant second. I get energized meeting younger men and women who care about wildlife and wildlands.

S-R: How much time do you devote to the business?

Pineo: Before I retired from the Department of Ecology, I spent 15 to 20 hours a week – nights and weekends – making falconry equipment. Now it’s more like 40. And all this would be impossible without Trish handling the books and keeping everything organized.

S-R: Is there a busiest time of year?

Pineo: Summer and fall are busiest, but the other months are starting to fill in as more people handle raptors at rehabilitation centers and zoos or use them in bird abatement to scare birds off airport runways, orchards, vineyards and landfills.

S-R: What do you like most about your job?

Pineo: Designing good products and interacting with customers.

S-R: How many hood makers are there?

Pineo: The number is growing – probably 300 or 400 globally – which I really encourage. I love to teach falconers to make gear, because that’s the tradition I came out of.

S-R: How much longer can you do this?

Pineo: We think maybe another year and a half. There’s strong, ongoing demand for our core products, and people will be very sad if we close the business. I have trouble letting go of stuff. Trish is more able to make transitions.

S-R: What sort of person is best suited for this career?

Pineo: As with any small business, you must be willing to work hard, put in ridiculous hours and be meticulous about quality. And you need good people skills, because falconers can be marginally socialized.

S-R: Looking back, is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

Pineo: I wish I’d figured out how to make an item everybody needs, or thinks they need, like a handbag or a cellphone. (laugh) That would have been much more lucrative.

Writer Michael Guilfoil can be contacted at mguilfoil@comcast.net.