At 60, Spokane resident completes grueling 2,745-mile bike-packing race

Some winds were so strong that Craig Schwyn wanted to curl up on the ground and cry.

Mud so thick the wheels of his carbon fiber Salsa Cutthroat bike balled up and he couldn’t ride. Snow. Ice. Trails so rocky and steep he had to get off and push 50 pounds of bike and gear for miles.

And yet, one of the harder parts of competing in a grueling 2,745-mile bike-packing race, was the 79-cent gas station burritos.

“The food was probably the worst piece of the whole thing,” the 60-year-old Schwyn said. “I like to eat and I never want to have to eat like that again.”

In June and July, Schwyn took 25 days, 15 hours and 49 minutes to complete the Tour Divide. The self-supported race that features no prize is considered one of the hardest – if not the hardest – endurance bike races in the world.

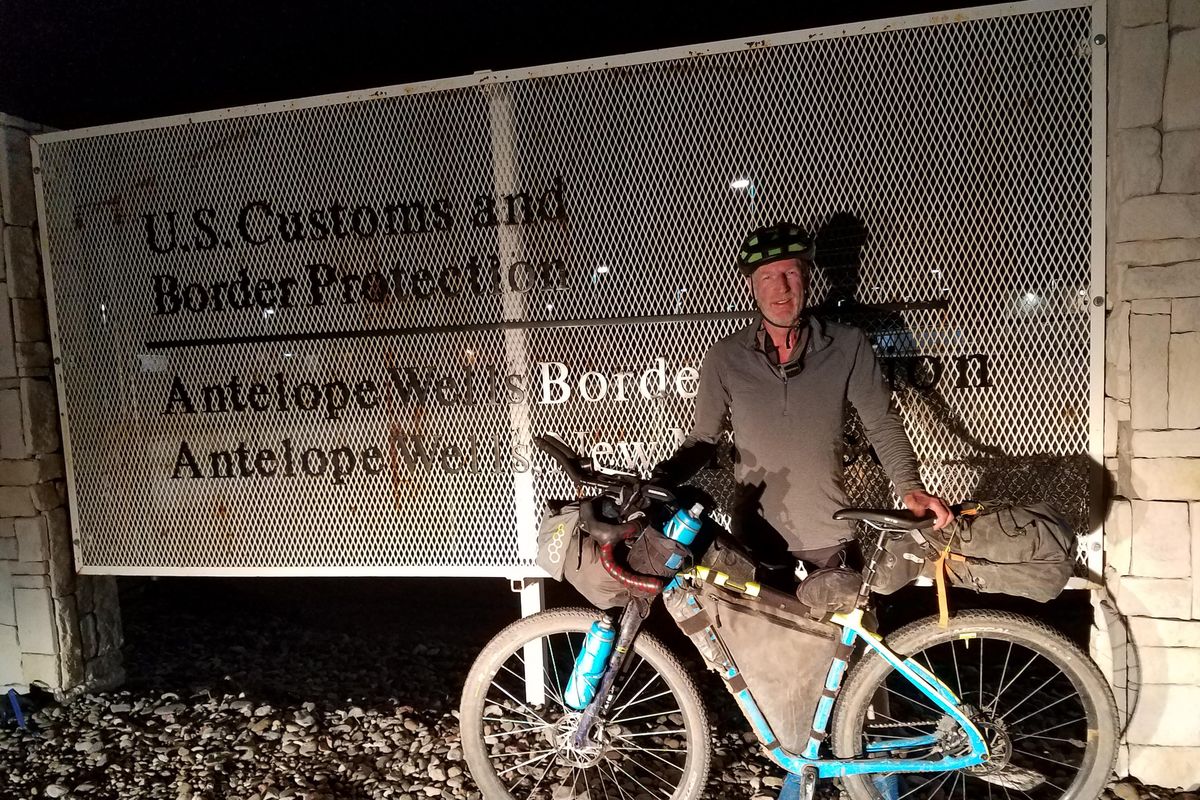

Competitors follow the continental divide leaving Banff, Alberta, in Canada on June 14 and finishing in Antelope Wells, New Mexico, on the Mexico-U.S. border. During the route, Schwyn climbed 175,980 vertical feet (equivalent to climbing Mount Rainier more than 12 times), crossed numerous mountain passes and dealt not only with weather, fatigue and terrain but also challenging route finding.

All of which to say there isn’t much time to eat.

“The leaders, they just don’t sleep,” Schwyn said. “Most of the pack doesn’t go any faster than I did. They just go with less sleep.”

Craig Schwyn rides his bike during the 2,745-mile Tour Divide. Schwyn, who finished in 25 days for an average of 106 miles per day, had never ridden more than 100 miles in a day prior to competing in the race. (Mitchell Clinton/COURTESY / COURTESY)

For his part, Schwyn would ride from dawn to dusk, which at this time of year means more than 12 hours of saddle time. Instead of packing a stove or food, he got high-calorie food from restaurants, convenience stores and fast-food joints.

Like 79-cent burritos from gas stations.

“You eat all this horrible food,” he said. “You go in and get the highest-calorie stuff you can. You buy three hamburgers and stuff them in your pack and eat them for 12 hours. Even though they’re hot.”

But like every part of the race, Schwyn trained for the gustatory challenges of nearly a month on the road, said Marla Emde, his personal trainer.

There were “quite a few” long training rides in the fall, winter and spring where Schwyn would head out with no food, she said. Instead, he had to buy whatever he could find from convenience stores and practice eating while biking.

“You have to find out if your gut can take all this stuff, too,” she said.

That sort of preparation underscores the meticulous ways in which Schwyn prepared for the race. In late September, Emde said he approached her and asked if she would train him. Originally, he’d considered doing the race in 2020, but decided to do it in 2019 instead. He started training in November.

“That’s not a lot of training time for an event that long,” Emde said.

An added factor? Schwyn had never ridden 100 miles in one go.

“I’ve never been in a bike race,” he said. “I’d actually never done a 100-mile ride before (this spring). I tried touring last summer for the first time.”

Still, Schwyn had ridden a fair amount. That’s one of the advantages older athletes have.

“Craig, he’s 60, yeah,” Emde said. “But he does have a lot of miles in his legs … over the years there is this accumulation that occurs. He’s not new to the sport by any means.”

Emde and her husband Michael are no strangers to training endurance athletes. Their company, Emde Sports, specializes in personalized training for triathletes, cyclists and other endurance athletes. She told Schwyn that he would have to spend “three to five hours on a trainer” during the winter.

He agreed, and for the next six months he trained nearly nonstop. As the race approached, and the Spokane weather improved, he ramped it up, riding 8-10 hours a day, four days a week, with between 7,000 and 8,000 feet of climbing a day.

“When I started, I was in tip-top shape,” he said.

That was good, because the first day of the ride was 112 miles with more than 10,000 feet of climbing.

“It really opens your eyes on what you’re getting into for the rest of the race,” he said.

Unlike other bike races, the Tour Divide has no stages and is completely self-supported. Competitors don’t pay an entry fee and there are no prizes for winners. For that reason, and because it’s such a long, difficult race, making it hard to watch, the race receives little or no media attention.

Instead, it’s truly a test of grit and determination, with each amateur competitor setting their own goals. The leaders, Schwyn said, are mostly trying to complete the course in 13 days or less, which would be a course record (the male course record is 13 days, 22 hours and 51 minutes, set by Mike Hall in 2009).

For his part, Schwyn had two goals: to finish the race and average about 110 miles per day, which would mean he’d finish the race in 25 days.

Just finishing is an accomplishment, with only 30% to 40% of riders finishing the race within the 30-day cutoff period.

“Mentally, it’s hard to keep going when you’re out there in the snow,” he said, “or it’s pouring rain.”

Thunderstorms and snow forced him to cut a few days short. A route-finding mishap cost him nearly a full day. That all meant that his 110-mile-per-day goal fell by the wayside.

“What plans I had to start just kind of went out the window after a while,” he said. “OK, I’m just going to ride all day long and get where I’m at. And some days that’s more than 110 and some days it’s less.”

On July 9, with more than 150 miles left before reaching the Mexico border, Schwyn was surprised when he looked at his phone and realized he could still finish the race in just over 25 days.

“I didn’t believe it,” he said. “I leaned over across the table and asked this old man … what day and date is it? He said, ‘It’s Tuesday, July 9.’ ”

That day he rode 175 miles, finishing the race by moonlight on paved road. His son picked him up in the early morning hours of July 10.

While his exhaustive training and packing (plus plenty of luck) were certainly keys to his success, Schwyn said maintaining a positive attitude was the key to finishing.

“If someone was around me and started talking negative, I just left immediately,” he said. “I didn’t want any negative thoughts in my head. And that’s what kept me going – always being positive. I was the luckiest guy in the world. I got to stomp on my pedals for 12 to 18 hours a day. Who gets to do that?”