Cabinet of curiosities: 15,000 ink samples at Secret Service

WASHINGTON – In a cabinet inside a modest laboratory in downtown Washington are rows and rows of ink samples in plastic squeeze bottles and small glass jars. To the untrained eye, it’s just a bunch of blackish liquid with strange names like “moldy sponge” or “green grass.”

But to the U.S. Secret Service agents who use the samples, they are the clues that could save the president from an assassination attempt. Or stops a counterfeit ring. Or identify the D.C. sniper.

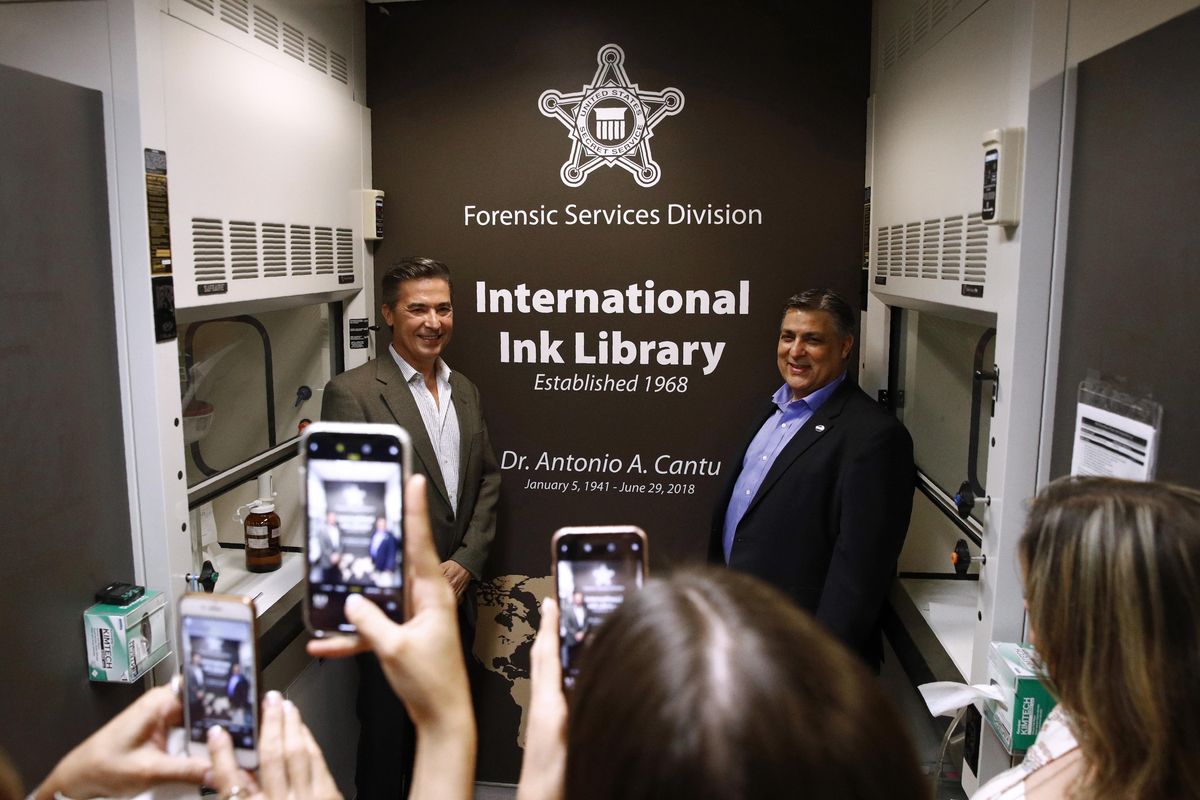

The ink library at the lab contains more than 15,000 samples of pen, marker and printer inks dating back to the 1920s. The collection is the result of one man, Antonio Cantu, a renowned investigator and former chief chemist at the Secret Service who started picking up samples in the 1960s. Cantu died unexpectedly last year, and the Secret Service recently dedicated the lab in his honor.

The library handles threat letters – the Secret Service protects not only the president but also other high-profile officials – and phony documents, ransom letters and memorabilia.

“About 15 years ago we started hearing, `Oh, this is going to die out, everyone is using computers,’ but that’s not true. Handwriting, written documents, it’s still such a large part of an investigation,” said Scott Walters, a forensic analyst for more than two decades who worked with Cantu.

Cantu pioneered static ink dating, in which scientists determine when ink was first made available to the public. So, for example, when a query came in recently about a letter purporting to be written by Abraham Lincoln, lab scientists could perform a check to see if the ink was from the 1800s, or the 1900s. Or that baseball signed by Babe Ruth? Turned out the ink wasn’t available when the Sultan of Swat was playing ball.

The lab is one of several under the Secret Service’s questioned documents branch, which is also responsible for handwriting analysis and document authentication, and handles as many as 500 cases a year. The branch works on Secret Service investigations, plus counterfeiting probes and fraud and helps law enforcement agencies around the nation and worldwide.

It handles an array of cases. In one, a New York City crossing guard had forged a dozen racist and offensive letters to police officers and a reporter. As it turns out, the guard was trying to frame a chiropractor as part of a bizarre feud, court documents showed. In another, a former studio assistant to artist Jasper Johns forged documents saying that pieces were authentic Johns’ works that the artist had given to him and he had the right to sell them. But they were really stolen.

Others cases were larger, like the 2002 Washington, D.C., sniper shootings that killed 10 people and critically wounded three. The shooters left tarot cards, including one Death card in which “Call me God” was written on the front and back. Cantu and his team analyzed the samples and helped crack the case.

Walters remembers analyzing documents from the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. “I could smell the fuel from the airplane,” he said.

Another colleague, Kathleen Storer, who recently retired, recalled analyzing a threatening letter that led to the prosecution of a man who would testify only with a paper bag over his head.

“That always sticks out in my mind,” she said. “He really didn’t want anyone to know he wrote the letter. We saw a lot of really unusual things.”

After Cantu died, Storer went through more than 16 boxes of books that he had acquired, with titles like “The Story of Papermaking,” “What Wood is That?” and “Pulp and Paper Manufacturing.” She created a small collection housed in the questioned documents division.

Both the ink library and book collection were named for Cantu. She said Cantu’s contribution to the field was invaluable – people would come to the Secret Service just to work for him. The 77-year-old was kind and patient, his friends and family said, and extremely humble. He loved teaching others, and investigating was his passion.

“He was so unassuming, you would never know he was so renowned in our field,” Storer said. “He was a gentleman, pure and simple, and I believe his intellect was greater than Albert Einstein, truly.”

His older brother said the family had no idea how renowned he was. Cantu was that good at keeping a low profile.

“Seeing this, it only makes us prouder,” his brother Vidal said at the dedication ceremony.

Lab director Kelli Lewis said they are constantly amassing new ink, as well as printer ink samples, taking clues from each new case and developing techniques to confront modern criminals.

“As the digitization of the world moves forward … people are printing currency on their home computers,” she said. “We’ve had to evolve with the library and so we’re looking at ink jet as well as writing samples from pens and markers.”