Tiny, beloved Spokane County school district has one 105-year-old school, 36 students and a superintendent pushing 90

Glenn Frizzell, the 87-year-old part-time superintendent of Great Northern School District visits the 5-6 classroom, Thursday, Jan. 24, 2019. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

The tiny hallway inside Great Northern School overflows with juxtapositions.

A charging station packed with iPads rests on a floor that predates World War I, while the man in charge checks in on students young enough to be his great-grandchildren.

The hall also fills with pride on a chilly Thursday morning as part-time Superintendent Glenn Frizzell, age 87, takes in the scene.

“The beauty of this place is that you can stand in one spot and see every kid in the school,” Frizzell said with a smile.

He’s right. A few feet away, the student body was hard at work – all 36 of them in three classrooms.

It’s the closest thing to a one-room schoolhouse in Spokane County, a 105-year-old building located on land donated in 1894 by the Great Northern Railway.

Think “Little House on the West Plains,” but with 21st century technology and forward-thinking leadership.

Glenn Frizzell, the 87-year-old part-time superintendent of Great Northern School District, visits the K-1 classroom, Thursday, Jan. 24, 2019. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Great Northern is old-fashioned in the best sense, where school musical performances and barbecues draw hundreds from the local community, where bonds pass with record approval rates and where the board of directors is almost unchanged since Frizzell took over in 1994.

“The Perfect School,” they call it in a district handbook, which is filled with testimonials about the less-is-more quality of education at the tiny public school.

Writes parent Linda Torretta: “The teachers at Great Northern instill a love of learning in our children through unconditional support, encouragement and acceptance of each individual’s learning style and temperament.”

Or as Frizzell says, “The kids come first.”

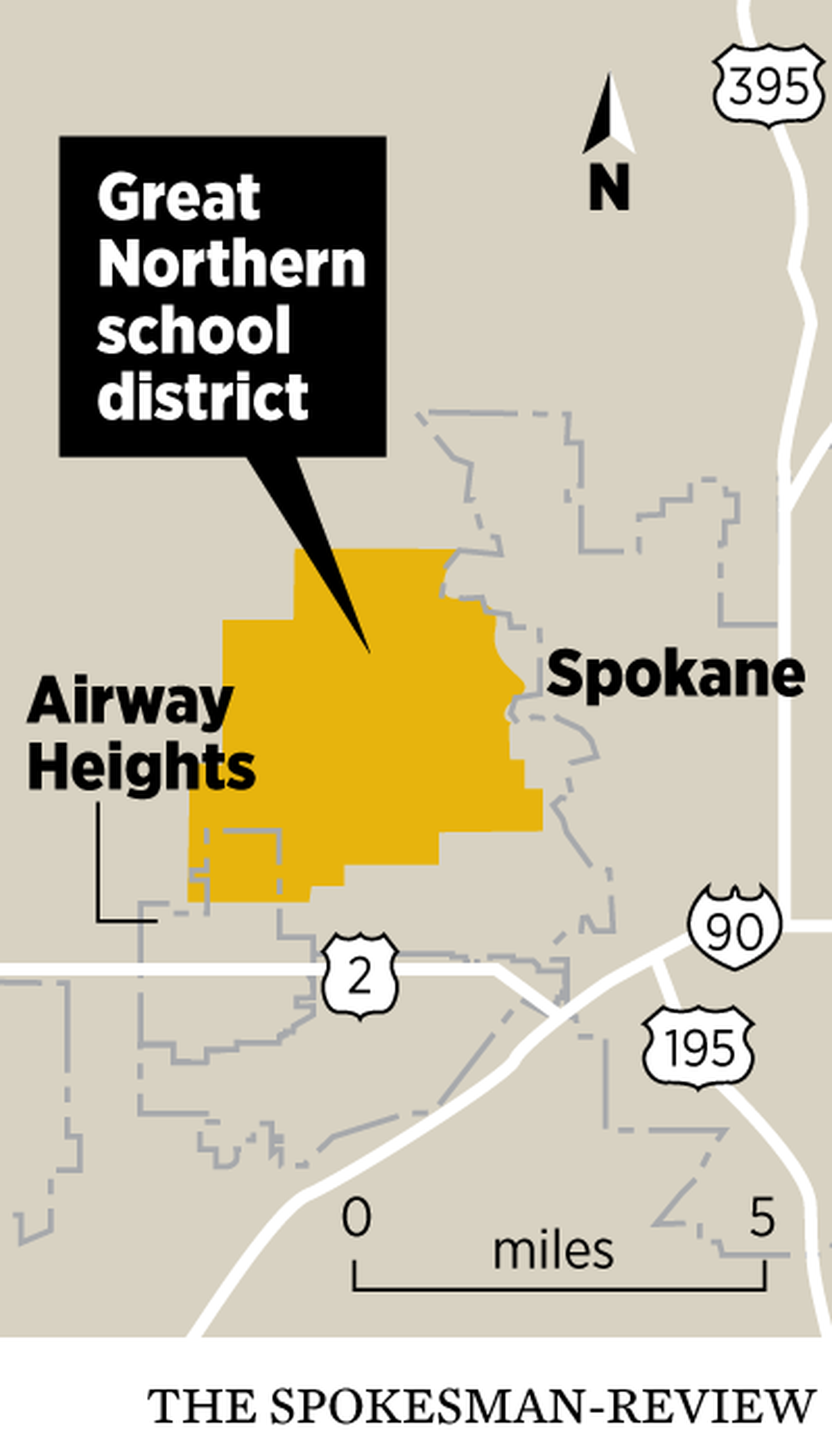

The building and the district – they are housed in the same building – are only 6 miles northwest of downtown Spokane, a gem hidden in the hills.

“How in the heck did you hear about us?” said Frizzell, a Portland native and Marine Corps veteran. He has worked in education for more than 60 years as a principal or superintendent in The Dalles, Oregon, and in the Washington towns of Stevenson, Wahkiakum, Dayton and Fife.

In 1987, Frizzell moved from Fife to Spokane, where he spent six years as an assistant superintendent with duties as varied as labor negotiations and helping start the Express Program.

Retirement, when it came in 1993, “lasted about six weeks,” said Frizzell, who with several others formed a business that helped short-staffed smaller school districts handle negotiations, investigations and headhunting.

“We could provide a service, and it paid for an elk-hunting trip or a salmon-fishing trip,” Frizzell said.

He also worked as an interim superintendent in several districts.

“It’s hard to hit a moving target,” Frizzell said.

In 1994, he found a new home as a part-time superintendent at Great Northern and another one-building in the Steptoe School District.

“I’d like to say I lead the staff, but they lead me,” said Frizzell, who often defers to secretary Jodi Finley.

“He used to scare me, and I don’t scare easily,” said Finley, who has a daughter in fourth grade at Great Northern.

“But he’s a lot of fun and he keeps me laughing,” Finley said. “He reminds me of my grandpa.”

However, Frizzell has no plans to retire anytime soon, and why would he?

“It’s a good reason to get up in the morning,” said Frizzell, who knows every detail about the school’s operation.

As a choice school, Great Northern accepts students from outside the district, many whose parents attended the school themselves and want the same experience for their children.

Employing what educators call the “portfolio” approach, students are grouped less by age than ability.

“We’ll move the kids between classrooms,” Frizzell said, “to challenge them or to help them. We move them around; a teacher says ‘How about me taking “Mary” for three weeks?’ ”

The payoff comes in Mary Johnston’s class, where overachieving second-graders sit with third-graders and some fourth-graders.

“We don’t have grades, we have skill levels,” Johnston said. “A lot of them are working above what most schools call ‘grade level.’ ”

“We have the freedom to choose our own curriculum, as long as they meet the (state) standards,” Johnston said.

Johnston has barely a dozen students, all of whom are engaged in the lesson, and even the shyest aren’t afraid to speak up.

Or to sing.

“Even in music class kids will get up and sing solos without thinking about it,” Johnston said.

Across the hall, Jodi Francis teaches kindergarten through second grade, while Eileen Nave works with fourth-, fifth- and sixth-graders.

Nave also serves as principal, one of several multitaskers at Great Northern. Johnston fills in as special education and Title I coordinator and homeless liaison, Finley doubles as a physical education teacher, and Steve Bahme serves as transportation director and paraeducator.

However, Great Northern offers more than the basics. Cindy Baumann teaches technology, Donna McMath handles music lessons and Karen Liere teaches art.

“None of this would work without them,” Frizzell said.

It isn’t perfect. The old school lacks access for the handicapped, and Finley runs a space heater full time in her chilly basement office.

Warmth comes from the people inside, which means the hardest thing about attending Great Northern is saying goodbye. Most graduates move on to large middle schools in Spokane, Cheney or Airway Heights.

When Finley’s older daughter reached sixth grade, the family talked about the choices: Northwood Middle School in Mead, where each grade has 200 students, or Assumption Catholic School.

“We gave her the option, and she chose Assumption,” Finley said.