This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: The 100-mile rule runs contrary to reasonable searches

In 1967, a Mexican citizen with a legal work permit was pulled over by Border Patrol agents on a California state highway.

The agents searched the car of the man, Condrado Almeida-Sanchez, and found marijuana. They had no warrant, and no reasonable suspicion of a crime. They were conducting random, roving patrols under a then-20-year-old federal policy that allowed warrantless stops and searches “within a reasonable distance” of the border.

This distance was defined, neatly, as 100 miles; Almeida-Sanchez was within 26 air miles of the Mexican border on an east-west highway that did not connect to the border.

The Supreme Court would later call the rationale underlying the 100-mile border zone “an extravagant license to search” that exceeded the Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure. In a 5-4 decision, justices threw out Almeida-Sanchez’s conviction on federal drug charges in 1973.

Does that case bear on the routine, random, warrantless bus searches now being conducted regularly by Border Patrol agents on buses at the city-owned Intermodal Center in downtown Spokane? Does it relate to the case of the Portland comedian, a Libyan asylee, who was hauled off a bus and questioned for 20 minutes, and then made his experience go viral on Twitter over the weekend?

Councilman Breean Beggs believes it does, and has cited that case in his arguments that Mayor David Condon should be enforcing a new city law requiring federal agents to present a warrant for searches on the bus station property. Condon argues that federal law exceeds the city’s authority, and thus he will not try to enforce it.

Legal experts argue about Almeida-Sanchez to this day. The fact that the nation’s immigration system has undergone significant changes in the past 40-plus years means it doesn’t operate as a neat precedent. The constitutional implications of the random searches may be a matter above the city government’s pay grade.

But it’s noteworthy that a large part of the Border Patrol’s discredited argument for stopping and searching Almeida-Sanchez – the extravagant license to search of which the Supreme Court was so dismissive – is the same one the mayor cites: the 100-mile border zone, in which agents can detain, interrogate and search people in ways that would be unconstitutional in the rest of the country.

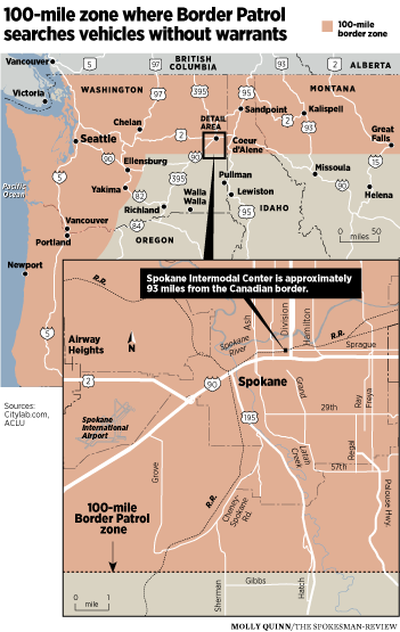

Civil libertarians see this 100-mile border zone as a constitutional mulligan zone for border agents. The Border Patrol argues that the zone, and particular points of travel within like bus stations, is the “functional equivalent” of the border.

Under this argument, Spokane’s bus station, which is 93 air miles from the Canadian border and which is a stop on east-west routes, is the functional equivalent of the border.

Thus federal agents board buses and perform “show-us-your-papers checks” that are exactly the kind of fishing expedition the Fourth Amendment seems designed to prevent. They impinge on the constitutional rights of everyone on every bus.

The experiences of the Portland comedian, Mohanad Elshieky, highlight the logical weakness of the 100-mile zone. As noted, Spokane is barely within this zone at all. Elshieky was riding a bus from Pullman, which is at least 70 miles away from the 100-mile zone, to Portland.

He was actually within Spokane’s little piece of the zone for a tiny, tiny fraction of his trip, and wasn’t traveling to or from a border. Not even close.

Was Elshieky traveling within the functional equivalent of the border? Is that where we live in Spokane – within the border? Does the Constitution touch us more lightly here, since we’re barely inside this arbitrary zone?

Obviously, a decisive answer requires something more than a somewhat related 1973 Supreme Court ruling and a debate among local elected officials. A case testing the constitutionality of the 100-mile zone and Spokane’s bus station might do it – Elshieky’s experiences could well form such a basis – but no such case seems to be on the horizon.

There is little more crucially American than the principle that we live in a country where the police are constrained from detaining, interrogating and searching you without a reason. Random, warrantless bus searches far from any border just do not square with this principle.

In that sense, the words of former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, who wrote the decision in the Almeida-Sanchez case and who expressed such a dim view of the 100-mile zone, still seem especially pertinent.

“It is not enough to argue, as does the Government, that the problem of deterring unlawful entry by aliens across long expanses of national boundaries is a serious one. The needs of law enforcement stand in constant tension with the Constitution’s protections of the individual against certain exercises of official power. It is precisely the predictability of these pressures that counsels a resolute loyalty to constitutional safeguards. It is well to recall the words of Mr. Justice (Robert) Jackson, soon after his return from the Nuremberg Trials:

“ ‘These (Fourth Amendment rights), I protest, are not mere second-class rights, but belong in the catalog of indispensable freedoms. Among deprivations of rights, none is so effective in cowing a population, crushing the spirit of the individual and putting terror in every heart. Uncontrolled search and seizure is one of the first and most effective weapons in the arsenal of every arbitrary government.’ ”