Sole surviving member of the South Selkirk caribou herd captured, Gray Ghosts are no more in Lower 48

Canadian wildlife officials pose with a sedated caribou. Canadian officials moved the sole surviving cow from the South Selkirk caribou herd, along with two caribou from the South Purcell herd, farther north to a 20-acre maternal pen near Revelstoke, B.C. (British Columbia Ministry of Forestry)

The sole surviving member of the South Selkirk caribou herd was captured by Canadian officials Monday.

The capture marks the end of the only herd that still occasionally crossed back and forth between Canada and the Lower 48 states.

“You know it’s sad. We’re still in mourning over the whole situation,” said Bart George, a wildlife biologist for the Kalispel Tribe of Indians. “The Selkirks lost some of their magic.”

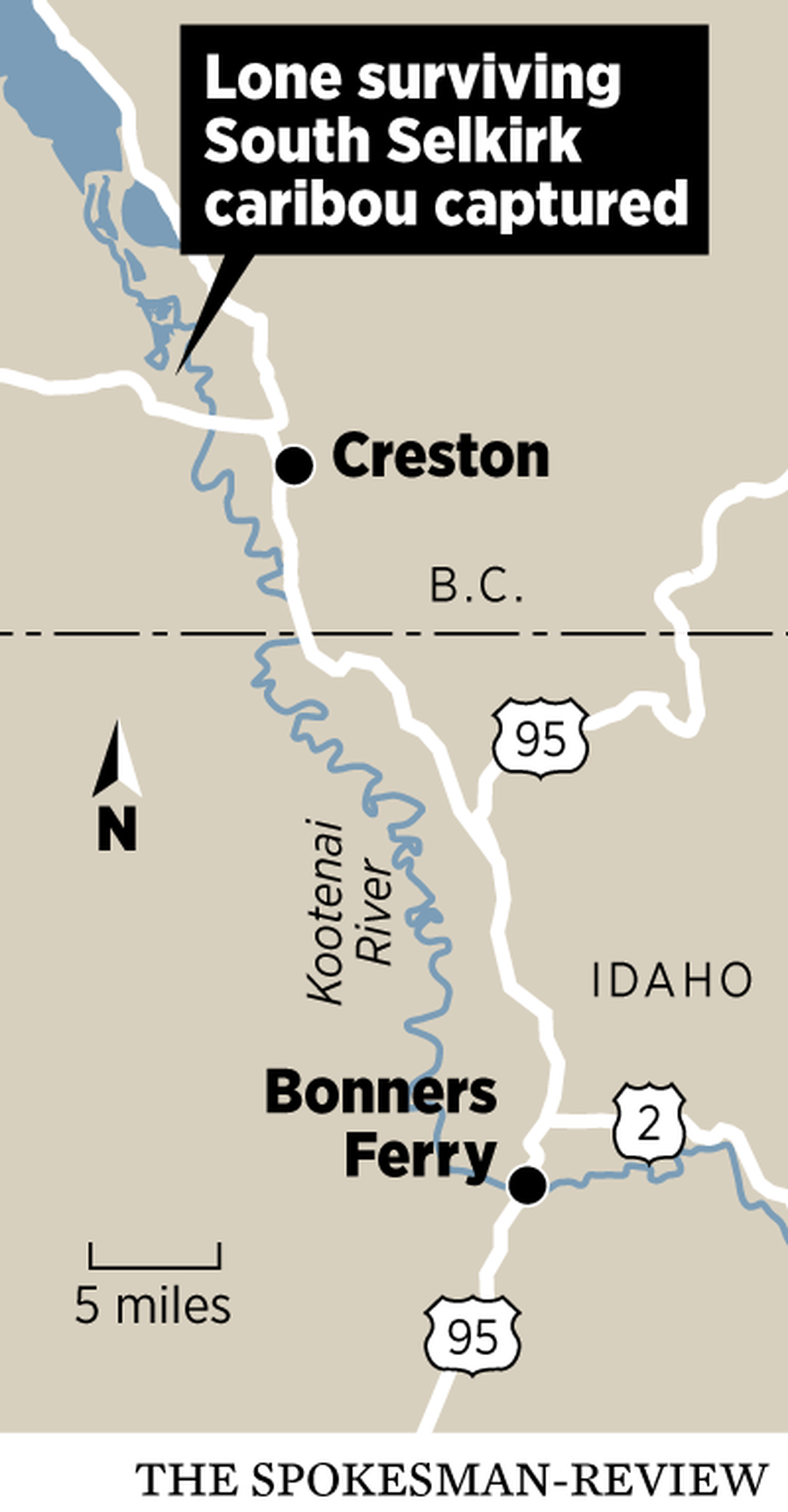

The female caribou was captured roughly 6 miles northwest of the town of Creston, B.C., in the Shaw drainage. Canadian officials moved the animal, alongside two caribou from the South Purcell herd, farther north to a 20-acre maternal pen near Revelstoke, B.C., said Leo Degroot, a wildlife biologist in British Columbia who has worked with caribou for 15 years.

The survivors will remain in the pen while they gain weight, he said. Eventually, they will be introduced into the adjacent Columbia North caribou herd.

“This is sort of a stopping point to see how they are doing,” Degroot said.

Two male caribou from the South Purcell herd were not captured because they remained under cover. Biologists capture caribou by shooting nets over them from helicopters. Degroot said he isn’t sure what will happen to those two males; biologists may capture them and move them to Revelstoke or they may leave them in the Purcell Mountains.

“They were standing under trees and wouldn’t come out,” he said.

Declining for decades

The species has been in decline for decades. In the spring, aerial surveys found only three animals left in the South Selkirk herd, all female. In 2017, there were about a dozen of the endangered animals.

Of the three caribou found in the spring, one was killed by a cougar and the second’s collar malfunctioned.

The Purcell herd also saw a precipitous decline during the same time period.

That’s despite multiple efforts over the years to revive the struggling species, including an expensive multiagency and multinational effort to transplant caribou into the Idaho and Washington Selkirk Mountains in the 1990s and in 2012.

Habitat degradation from old-growth logging, climate change and increased predation has decimated the species.

Mountain caribou, unlike tundra caribou, use their wide feet to walk on top of deep snowpack. That allows them to reach lichen growing high on old-growth trees. The South Selkirk herd ranged through the high country along the crest of the Selkirks near the international border. The remaining 14 or so herds are all in Canada. It’s estimated that fewer than 1,400 mountain caribou are left in North America. At one point, scientists believe caribou roamed as far south as the Salmon River in Idaho.

“We’re hopeful for the future but pretty disappointed with the whole situation,” George said. “The caribou didn’t have many allies.”

One of the animals’ few allies in the United States was the Kalispel Tribe. In 2017, the tribe helped organize a maternal pen project aimed at capturing pregnant cows and letting them calve in the security of a 19-acre enclosure. The tribe raised roughly $225,000 toward that effort, but the caribou population declined before they could implement anything. Then in November, Canadian officials announced their plans to move the surviving members of the South Selkirk herd farther north.

What’s next?

George said the Kalispel Tribe will remain involved in caribou recovery, although he’s not sure exactly in what capacity.

Canadian officials plan to implement a captive breeding project somewhere in British Columbia, with plans to eventually release caribou back into the Selkirk and Purcell ranges, Degroot said. George hopes the project is based in the Selkirks so tribal involvement is easier.

Some money from the maternal pen project could be used for the Canadian effort, George said. The hoped-for captive rearing project is still a year or two from realization, Degroot said. But if it happens, animals reared in captivity would be released into the Selkirk and Purcell ranges.

As for the three caribou transported to the Revelstoke pen, they will be introduced into the local caribou herd. A member of the adjacent population might be put into the pen, giving the animals a chance to get to know each other.

“Caribou are like cattle, deer or elk or whatever,” Degroot said. “They are very social animals and have a pecking order.”

Then all the animals would be released with the hope that the resident caribou would show newcomers the way.

With the removal of the elusive ungulates, some worry the Canadian government will eliminate rules that prohibit logging, snowmobiling and other activities in the caribou range.

“Our concern is that some of those restrictions will be lifted and in the future the entire habitat protection could be lifted,” said Candace Batycki, a program director at the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. “There are a lot of pressures to reopen that landscape to logging again.”

Already, Batycki said, snowmobiling permits are being issued for areas where caribou traditionally roamed.

“These are not unfounded fears,” she said.

Degroot confirmed that snowmobiling permits can now be issued for the Selkirks, although none has been yet. The intent behind the snowmobiling ban was to protect caribou from disturbance. Now that there are no caribou, the government has no reason to keep snowmobiles out, he said.

But he said the overall habitat protections – particularly the logging ban – will not be lifted.

“The plan right now is that habitat protections will remain in place,” he said. “Because, of course, if you start logging again that’s a long-term decision. Those habitat protections, forestrywise, will remain in place.”

A moment for Grace

There is a glimmer of hope, Degroot said.

In July, Canadian officials released about 20 cow caribou and their calves from the 20-acre pen near Revelstoke. Shortly after being released, one of the cows was killed by wolves.

Somehow, her month-old calf survived. The calf made her way back to the maternal pen where she’d been raised. Biologists spotted the newborn on trail cameras and let the baby back into the pen where she’s lived since, safe from predators but also the only caribou around.

“She was probably thinking that this is pretty lonely,” Degroot said.

On Tuesday, she got unexpected company when the three caribou from the Selkirks and Purcells were put in the pen. The calf, which is now 7 months old, “looked pretty excited,” Degroot said.

Normally, biologists don’t name the caribou they study, instead referring to them in the cold precise language of serial numbers.

But this lone calf was different. They named her Grace.

A few hours after the survivors of the Selkirk and Purcell herds were dropped off, Grace was rubbing noses with the new animals and following one of the cows around.