Getting There: The curious case of Benjamin Burr

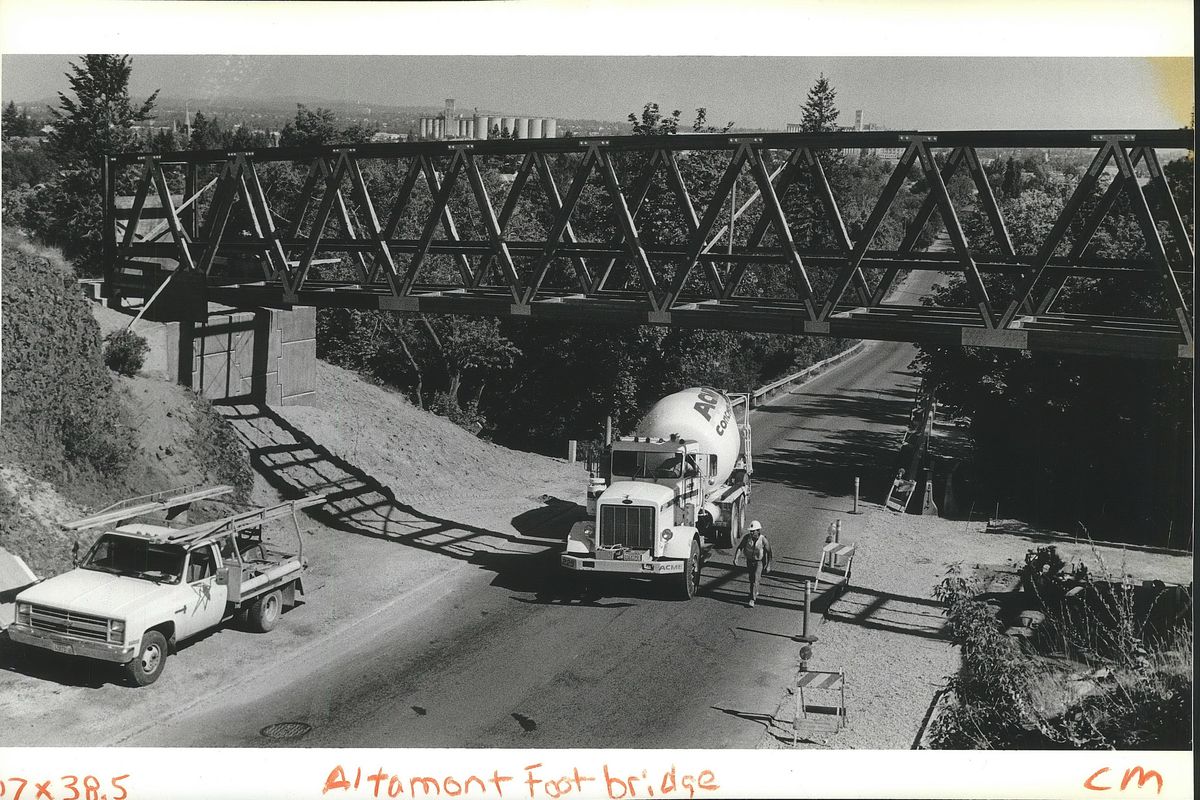

Below the Hamilton overpass, on the far end of the University District, an intersection of bicycle and pedestrian routes is taking shape.

While the area has been largely forgotten, or at least advisedly avoidable, in recent decades, it’s becoming a non-motorized crossroads, where the Centennial and Ben Burr trails meet, where the bikeways of Martin Luther King Jr. Way traverse, and where the new bicycle and pedestrian bridge takes to the air, spanning the railroad tracks with curvy, cable-supported splendor.

In all, this crossroads is a knot of routes coming from the East Central, Logan, Rockwood and Lincoln Heights neighborhoods, and downtown, too.

We should call it Ben Burr Crossing.

Critics have skewered the unimaginative name of the University District Gateway Bridge. And let’s be honest, “Centennial Trail” does nothing to describe the 61 miles of paved trail that follows the Spokane River’s path from Nine Mile Falls northwest of Spokane to Coeur d’Alene.

Then there’s Ben Burr, that mysterious name that’s attached to a trail, a boulevard and a road, not to mention a very quaint park.

But who was Ben Burr?

A Spokane & Inland Empire Railway Co. electric interurban train is pictured in 1912 on Main Street, just west of Post Street. Parts of a line that connected downtown Spokane to Colfax, Moscow and other Palouse points have been turned into roads or trails and named for Ben Burr. (Spokesman-Review archives)

Put simply, Burr was into transportation. As chief engineer for the Great Northern Railroad in Spokane for decades, his life was defined by it, up until his last moments, when he ran a red light in his car at Post Street and Second Avenue in 1965.

Perhaps more interesting, though, is what his name is attached to: parts of an old electric railway route that connected Spokane to Colfax, Moscow and other points on the Palouse.

First, about Burr.

Burr was chief civil engineer for the Spokane division of the Great Northern, where he spent his entire career before retiring in 1953 after 48 years of service.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of railroads in Spokane history, especially the Great Northern. Without that industry, the city wouldn’t exist. Without the Great Northern, Hillyard most definitely wouldn’t exist, as it was that company’s creator, James J. Hill, who directed the rail lines to run through his “yard.”

Not to mention the fact that in 1892, the Great Northern built a depot on Havermale Island in the city center. Not much is left of it, except the clock tower that essentially symbolizes Spokane.

More broadly, the railroads that ran into and through Spokane made it the hub of a growing, industrialized Inland Northwest, spurring the city’s expansion. To this day, trains rumble through on a near constant basis. In the depths of any given night, the sounds of the city have quieted, but the trains continue to move.

Burr first moved here in 1905, in the midst of this early growth. Born in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, in 1886, Burr was not yet 20 when he came to Spokane as a chainman for the Great Northern. Over the next decade, he became a construction engineer and surveyor during the building of numerous rail lines through Eastern Washington, North Idaho and western Montana.

After serving as an Army officer in France during World War I, and working for Great Northern in Havre, Montana, Burr was named Spokane’s district engineer in 1929, where he remained until he finished his career 24 years later.

If all this sounds like enough to get things named after Burr, it wasn’t. Instead, it was his work after retirement.

Before that, though, a word about the Spokane and Inland Empire Railroad Co.

In 1903, an Idaho lumberman named Frederick Blackwell opened the region’s first “interurban” line, connecting Spokane to Coeur d’Alene by electric train.

For decades, the city had been served by electric streetcars, but getting between all the cities and towns in the region proved difficult. With Blackwell’s new venture, the trip between Spokane and Coeur d’Alene was suddenly quick and easy.

Seeing the success of the interurban line, J.P. Graves partnered with Blackwell the following year and built another interurban electric line into the Palouse, and, together, the men and new lines formed the Spokane and Inland Empire Railroad Co.

This second line left downtown Spokane and crossed toward Gonzaga University before heading south. Following the contours of the land and population centers, the line wiggled this way and that before it came to Spring Valley Junction, just northeast of Rosalia. There, it split into two lines: one ended in Colfax, the other in Moscow.

But with cars and pavement on the horizon, the interurban lines weren’t long for this world. In 1929, the company merged with the Great Northern, and the interurban system was largely abandoned.

That just so happened to be the year Burr returned to the Great Northern, and with that the fate of the old interurban rights-of-way was decided. Decades later, in his retirement, Burr would work to get this old line into public hands, as road or trail. The three paths named for him – Ben Burr trail, boulevard and road – all run along the old Palouse interurban line.

The first of these named after Burr was Ben Burr Boulevard, a curved and short bit of road in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood that crosses Freya Street between 14th and 15th avenues. Though he said he was “quite thunderstruck” when the half-mile road was named for him by the Spokane City Council, a June 1955 article in The Spokesman-Review described his central role in persuading his former employer to sell the abandoned road to the city.

Not far from the road’s western terminus, where it turns into Thor Street, is the eastern end of the Ben Burr Trail – probably the best known of the Spokane sites named for Burr. Again, Burr was instrumental in getting the Great Northern to transfer the land to the city, this time to its parks department.

The final part named for Burr, the 1.5-mile Ben Burr Road, is also for autos, but it supplies a great bicycle route for those daring enough to surmount Tower Mountain.

A fourth stretch of the old interurban line is a paved path that runs between 57th and 44th avenues near the Palouse Highway. In the mid-200s, Spokane County protected some wetlands and built the pathway at the same time. The official title: The Ben Burr Pathway and Wetland Enhancement Project.

Putting aside any grousing about the tragedy of losing fully electric transportation between the city centers of the Inland Northwest, it is easy to wish that the old Palouse line had been preserved and paved as a multi-use trail. A recent bicycle expedition of the line by this intrepid columnist proved impossible. Where the line wasn’t saved by Burr, it was turned into houses, backyards and other private property.

So while the route of interurbans are mostly lost to time, some stretches will always be remembered. Thanks to Ben Burr.

Arizonans attack autonomous vehicles

The people of Chandler, Arizona, have had enough Google testing its self-driving cars in their town.

That’s the takeaway from a recent article by the Arizona Republic, which cataloged “at least 21 interactions documented by Chandler police during the past two years where people have harassed the autonomous vehicles and their human test drivers.”

The reporting, which was later taken up by the New York Times, reads almost like a science fiction novel where the unsuspecting citizenry suddenly realizes their town is being taken over by aliens.

One man “slipped out of a park around noon one day in October, zeroing in on his target, which was idling at a nearby intersection — a self-driving van operated by Waymo, the driverless-car company spun out of Google,” the New York Times wrote. “He carried out his attack with an unidentified sharp object, swiftly slashing one of the tires. The suspect, identified as a white man in his 20s, then melted into the neighborhood on foot.”

In August, a Waymo test driver saw “a bearded man in shorts aiming a handgun at him as he passed the man’s driveway” and called the cops, who charged the man with aggravated assault and disorderly conduct, and confiscated his .22-caliber Harrington and Richardson Sportsman revolver.

In June, a driver of a Chrysler PT Cruiser wove between lanes of traffic while taunting a Waymo van, but the company declined to press charges.

Lastly, in August, Charles Pinkham, 37, stood in the street in front of a Waymo vehicle, blocking its foward motion. Police approached him.

“Pinkham was heavily intoxicated, and his demeanor varied from calm to belligerent and agitated during my contact with him,” Officer Richard Rimbach wrote in his report. “He stated he was sick and tired of the Waymo vehicles driving in his neighborhood, and apparently thought the best idea to resolve this was to stand in front of these vehicles.”

Say goodbye to Seattle’s Alaskan Way Viaduct

On Jan. 11, motorists of Seattle will finally and forever bid adieu to the Alaskan Way Viaduct, the double-decker elevated freeway that cuts through the heart of downtown Seattle along the city’s waterfront.

It’s being replaced by an underground tunnel, but that won’t open until three weeks after the viaduct closes.

According to the Washington State Department of Transportation, the tunnel is “a direct, 2-mile trip underneath downtown Seattle. The tunnel entrances and exits, near Seattle’s Space Needle to the north and the stadiums to the south, work differently than the entrances and exits on the viaduct.”

The viaduct, which was built between 1949 and 1959, is a victim of its age – and location in the Cascadia subduction zone. Engineers say the elevated road would collapse in the event of a major earthquake.

Anyone worried about what will take the place of the viaduct shouldn’t be worried, obviously. But take heart in the events following the 1989 earthquake in California’s Bay Area. It severely damaged the double-decker, elevated Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco. The “blight by the bay,” as the San Francisco Chronicle called it, had to be demolished.

The unobstructed view of the bay is much nicer now.

WSDOT wants artists

The Washington State Department of Transportation is launching an artist-in-residence program, and applications are due today.

Washington is the first state to house an artist in a statewide agency, and let’s all rejoice that it’s the transportation agency.

Many organizations have contributed to the program. ArtPlace America is providing a $125,000 grant for the program, including a $40,000 stipend for the selected artist and $25,000 for a final project the artist and staff develop. Transportation for America will administer both the funds and the overall program, including providing staff and consulting assistance.

According to WSDOT, the residency will be a year long, and the artist will take four months to cycle through “WSDOT’s core divisions to gain knowledge on the agency’s operations, priorities and challenges. The artist will then propose projects to address WSDOT’s overarching goals while improving community engagement, supporting alternatives to single occupancy vehicle transport and enhancing safety and equity.”

The remaining eight months will be devoted to whatever project the artist decides to do.

For more information, visit smartgrowthamerica.org/program/arts-culture/wsdot-air.

Water work blocks McClellan

McClellan Street near Ninth Avenue will see some restrictions following two water line leaks.

Though the leaks are patched, the city has to go and replace the asphalt it laid temporarily with a concrete patch.

As the city notes, concrete is better at handling winter weather at the bottom of this hill.

As such, the northbound curb lane near the intersection of Ninth and McClellan will be closed from Monday, Jan. 7, to Wednesday, Jan. 9. After that, the northbound left lane in the same area will be closed from Thursday, Jan. 10, to Monday, Jan. 14.

This article was changed on Jan. 8, 2019. An earlier version of this article incorrectly said a path between between 57th and 44th avenues near the Palouse Highway wasn’t named for Ben Burr. In fact, it’s called the Ben Burr Pathway and Wetland Enhancement Project.