His family says he stopped using heroin. Then he relapsed in the Grant County Jail.

Derek Batton sat outside his sister’s house near Soap Lake, Washington, smoking cigarettes and talking on the phone with his fiancee about bail bonds.

A police officer was watching over Batton and his brother-in-law, waiting for sheriff’s deputies to sort out a domestic spat that had resulted in a 911 call. It was still hot on this Friday night in August, and the officer didn’t find it necessary to make a cooperative man wait in the back of a patrol car.

Batton knew he was going to jail, though it had nothing to do with this latest mess. The 34-year-old had some active warrants out of Lincoln and Kittitas counties stemming from charges of driving under the influence and driving with a suspended license. He worried the consequences this time would be especially severe; a judge had previously suspended part of a prison sentence on the condition he stay out of trouble and get treated for his heroin addiction.

Batton told his fiancee “I love you” and ended the call so the officer could put him in handcuffs. He showed no sign of recent drug use and said he could pee in a cup right then to prove it. The officer put Batton in the front seat of his patrol car for the 20-minute ride to the Grant County Jail in Ephrata. On the way, Batton joked that the facility was full and so he’d have to be let go.

The jail, however, was the last place Batton ever saw. Two days after he was booked, a corrections deputy went to deliver cleaning supplies to Dorm E, the holding area where Batton was being held with seven other inmates. Batton lay still in his cot, and another inmate remarked that he was not doing well. The deputy touched Batton’s foot to get his attention, but it was cold. He had died of an opioid overdose.

Now another man faces a charge of controlled substance homicide for allegedly smuggling drugs into the jail and doling them out to his cellmates in Dorm E, including Batton.

Grant County sheriff’s detectives say Jordan D. Tebow, 35, dispensed some kind of opioid, Suboxone strips (used for treating opioid addiction) and Seroquel (an antipsychotic medication), which he had allegedly hidden in his mouth or rectum to get through the booking process.

Cellmates consistently pointed to Tebow when asked by detectives about the source of the narcotics, according to recorded interviews and more than 100 pages of records that The Spokesman-Review obtained through a public records request. Tebow also faces charges of drug possession and delivery, and a count of intimidating a witness.

Yet Batton’s family is also frustrated that no one prevented his death. After snorting what is believed to be heroin on the evening of Aug. 11, Batton lay down and snored heavily through much of the night – a common sign of an overdose. One inmate told investigators that a corrections deputy walked by and remarked, “Wow, I wish I could sleep like that.”

The snoring finally stopped around 3 or 4 a.m., inmates told investigators. Batton didn’t wake up when someone turned on the lights shortly afterward, or when it was time for breakfast. It was almost 11 a.m. when officials realized he was dead. Deputies at the jail are equipped with naloxone, but by then it was too late to administer the life-saving, overdose-reversing drug.

Batton’s fiancee, Tiffany Hagadorn, said he relapsed and went to prison shortly after they met in 2016, but she believes he had been clean ever since. He would have celebrated two years without heroin this Jan. 26, she said. They had planned to get married in June.

Hagadorn said she was not surprised that Batton relapsed again in jail. Home life had been stressful. He was juggling court dates, check-ins with his probation officer, a job at a tire store and his newfound role as a stepfather to her four young children. The last thing Batton needed was to be locked up with a guy slinging free dope.

“You know, like, ‘Everything is falling apart, (things) aren’t going correctly, there’s dope sitting right here in front of me, I’m back in jail, let’s get high,’ ” Hagadorn said. “I can totally see where his mind was set.”

She does not want Batton’s final days of confinement to be the image that everyone remembers when they think about him. He deserves better than that, she said.

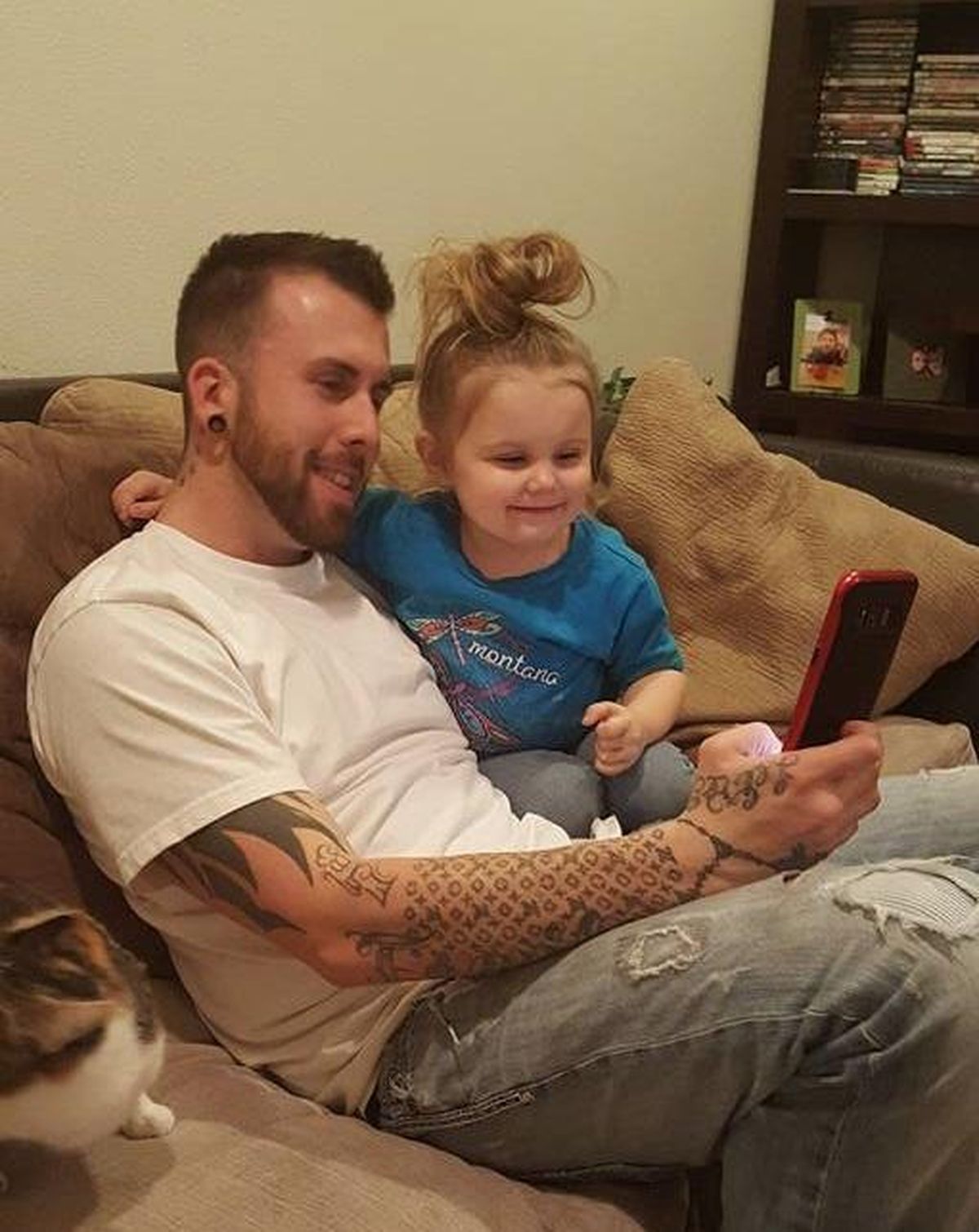

“I don’t want him going out with people saying, ‘Oh, that’s typical. We knew it was going to happen sooner or later.’ Because he was changing his life,” Hagadorn said. “I’m terrified that people are going to just see him as that junkie because that’s not who he was. He was a father who stepped up for four kids that weren’t his.”

Even before Batton’s death, Grant County officials were working to stem the flow of contraband into the jail. Several inmates were hospitalized following overdoses last year.

After Batton’s death in September, the county commissioners approved $371,000 to purchase an X-ray scanner for the booking area to detect items hidden in body cavities, as well as another scanner to check inmates’ mail.

Kyle Foreman, a spokesman for the Grant County Sheriff’s Office, said some arrestees are well aware that jail staff need probable cause to justify invasive cavity searches, and so it had been difficult to seize contraband without the aid of technology.

“A lot of people seem to think that just because you go to jail you automatically get a cavity search, and that’s just not the case,” he said.

Tebow – the man accused of smuggling the drugs that killed Batton – was arrested Aug. 11 on warrants for forgery, second-degree theft and driving with a suspended license. When he arrived around lunchtime in Dorm E, Batton had already been there for a night – sober, by all accounts.

Dorm E is a large “pre-classification” area where inmates wait to be assigned permanent cells. It has beige-painted cinderblock walls, two round wooden tables bolted into the concrete floor, and a shared restroom area with a metal toilet and urinal. Behind an unlocked door and five shatter-proof glass windows, inmates can reach a small “patio” area surrounded by high concrete walls. Sunlight streams down through a metal grate covering the top.

According to investigative records, a surveillance camera captured Batton snorting something off the ground of the patio on the evening of Aug. 11, accompanied by Tebow. One inmate said they both appeared high when they reentered the room and lay down on their cots.

The same inmate said that Tebow later threatened him, telling him not to tell deputies about the drugs or Batton’s condition. Another recalled Tebow saying he had “served him up,” meaning he had given drugs to Batton.

A few hours after Batton was pronounced dead, a corrections deputy found a small white packet for the Suboxone strips near a cellmate’s cot in Dorm E. Tebow had also been found in possession of drugs, the records state, even though he and his living cellmates had been moved to another dorm.

In an interview on Aug. 13, Tebow told detectives it was Batton who smuggled the drugs into jail. Tebow claimed he had stolen the Seroquel tablets, which he called “sleeping pills,” from Batton while he lay motionless in his cot.

The charges against Tebow were filed last month in Grant County Superior Court. Chris Bugbee, the Spokane attorney representing him, said he couldn’t go into much detail about the case, but he noted how many inmates were housed in Dorm E and that several were found to have used the drugs.

“There is quite a number of people over there who could have been responsible for that controlled substance,” Bugbee said.

Batton grew up in North Bend, Washington, and went to high school in nearby Renton. He was a car guy, and worked at a garage near his house in Moses Lake, mostly doing oil changes and brake replacements.

Whenever he had some money to spare, Batton poured it into customizing his pickup truck, a white GMC with big black rims. He also “spoiled the hell” out of the children, taking them out to get ice cream or to the local BMX track, said Hagadorn, his fiancee.

“He was the best thing that ever happened to my kids,” she said.

The couple went through ups and downs. He spent a night in jail after a particularly bad fight last May, though she said she never wanted to press charges. Neither she nor Batton’s mother, Barb Anderson, believes he intended to overdose that night in jail.

“He loved life too much,” Anderson said.

“Maybe he relapsed a few times, but he was really trying hard,” she said. “And I have to give him credit for that because some people don’t ever stop.”