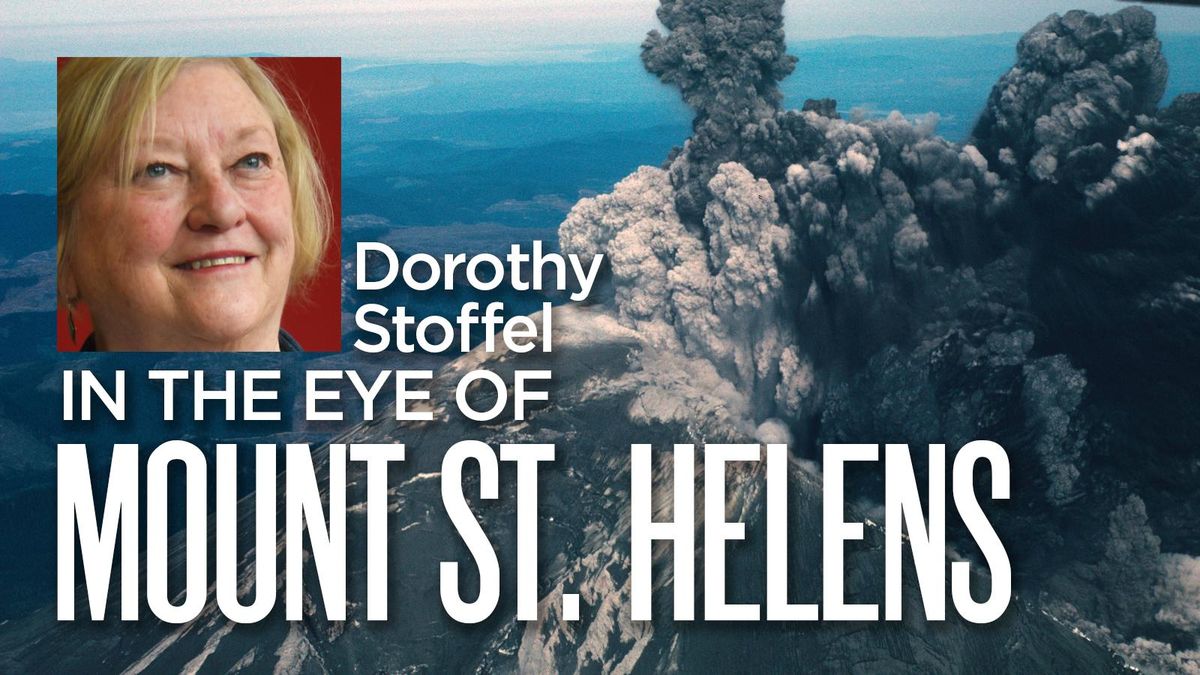

In the eye of Mount St. Helens: Spokane couple was flying above volcano’s eruption on May 18, 1980

Spokane resident Dorothy Stoffel’s 31st birthday present almost killed her. On the morning of May 18, 1980, with the encouragement of her husband, Keith, who rationalized the expense as an early birthday gift, Dorothy hired a small plane and a pilot to take the couple for a tour over Mount St. Helens.

No one predicted that the Stoffels would be flying directly over the site of the most disastrous volcanic eruption in U.S. history. When Mount St. Helens blew, it spewed 540 million tons of ash over 11 states and killed 57 people. And two Spokane residents had front row seats.

The Stoffels’ story will be part of an exhibition that opened Saturday at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture marking the 40th anniversary of the Mount St. Helens eruption. “Mount St. Helens Critical Memory 40 Years Later” arrives just in time to entertain and educate families and friends looking for engaging conversation starters over the holidays. Maybe even the children will pause to learn about the science of volcanoes in their own backyards.

The museum is asking residents who recall the eruption to attend and share their personal tales and mementos from that devastating day. The MAC’s new curator of history, Freya Liggett, has assembled artifacts, film, photography, recordings, firsthand accounts and virtual experiences to examine how the 1980 eruption has advanced our understanding of volcanoes more than any other eruption in history.

She plans to continue to update the exhibit by incorporating new stories and items brought in by Spokane residents who visit the exhibit, as well as from others in the region with tales to tell. Those wishing to share their memories also can add to the interactive archives online on the exhibition’s webpage.

Many longtime Spokane residents vividly recall the sudden plunge into darkness when the volcano’s massive ash cloud descended on the town. Back then there was no warning when the ash blotted out the sun throughout central and Eastern Washington. Some even feared it was the start of World War III. The choking volcanic dust smothered crops and transportation routes. Few could conceive that a natural event occurring 250 miles away would disrupt everyday life in Spokane for weeks.

Dorothy Stoffel had a bird’s-eye view for the earth-shattering event that rocked Spokane’s world 40 years ago. She is now retired and living in a cozy 1908 craftsman on Spokane’s South Hill. She likes to quilt, do jigsaw puzzles, attend the symphony and visit the MAC with friends. She just finished a two-day filming with National Geographic, which plans to air a show next year to mark the upcoming 40th anniversary of the eruption.

With light-blue eyes and a warm, ready laugh, Stoffel lights up when the conversation turns to her lifelong passion – science. “It’s important to me that people understand how different our continental Cascade volcanoes are from Hawaiian volcanoes,” she said with an exasperated smile. “People equate the two, but lava flows from Hawaiian volcanoes are usually extremely slow and a lot less dangerous.”

Stoffel knows firsthand how the 10 active volcanoes lying within 300 miles of Portland still possess the potential to destroy large swaths of the Northwest region. While her own career turned to wastewater cleanup efforts in the years after the eruption, she has shared her story with other scientists and journalists countless times to help them more accurately predict when an eruption might occur. Her up-close observations have been credited with changing opinions and saving lives.

Stoffel readily admits her experience above the eruption changed her.

“I don’t take life for granted,” said Stoffel, who has two sons and has since divorced. “There are very few women who are 70 who say they don’t mind getting older. I count these last 40 years as a bonus.”

On that fateful spring day in 1980, the Stoffels, both geologists, were visiting Yakima so that Keith, who worked for Washington’s Geological Survey, could give a lecture on the volcano’s recent reawakening. Dorothy, who had taught Geology 101 at Tacoma Community College before taking a job just weeks before at a Spokane engineering firm, couldn’t resist the chance to observe the reactivated volcano up close.

For nearly two months, a series of earthquakes had rumbled underneath Mount St. Helens, attracting scientists like the Stoffels. There had even been an explosion of ash that had blown a 250-foot hole in the mountain. There also was a pronounced bulge on the north side as if the mountain was pregnant.

An evacuated danger zone (which was later criticized as being woefully small) had been designated to keep the public safe. But as scientists, the Stoffels were able to get special permission to fly into the red zone. They were reassured by a U.S. Geological Survey scientist who gave permission to them to fly that “nothing is going on at the mountain today,” Dorothy Stoffel recalled.

It was a sunny and clear spring Sunday as the Stoffels’ hired, single-engine Cessna reached the volcano about 7:50 a.m. After 45 minutes of circling the mountain and taking photos through the windows, the couple and their pilot, Bruce Judson, decided it was safe to fly across the crater itself.

Dorothy Stoffel’s initial nervousness about flying for the first time in a small plane had abated by then. She even recalled feeling a twinge of regret.

“We made two passes directly over the south crater wall, and what really struck me was how serene everything was, and, surprisingly, I had this sense of disappointment,” Stoffel said. “I thought, ‘Oh, there was all this amazing activity for weeks, and now we’ve missed it all. The mountain has become dormant again.’ ”

That’s how peaceful it was that morning. Right before hell broke loose at 8:32 a.m. The first thing Dorothy Stoffel noticed was that the mountain appeared to be “weeping” on one side as ice and snow melted just on the bulge area. “I turned to Keith and said, ‘Hmmm, look at that. That must mean the heat source is getting near the surface,’ ” she said.

“So as we are flying, finally preparing to head back to Yakima, we are directly above the north side above the apex of the bulge, when, all of a sudden looking at the south side of the mountain, we saw a glacier falling into the crater,” Stoffel said. “I got excited, I thought ‘Oh, finally, a little activity!’ ”

The “activity” was a magnitude5 earthquake shaking the mountain, eventually triggering the sequence of events leading to the eruption. The earthquake caused a debris landslide.

“The whole north half of the mountain that we were flying just 500 feet above began churning, and a milelong fracture shot across the mountain,” Stoffel said. “Faster than our minds could absorb, the north half of the mountain just became like fluid and slid away.”

Stoffel then witnessed and photographed the largest landslide in recorded history. That removal of debris from the mountain took the pressure off the volcano’s structure, causing a horizontal blast of ash, rocks and steam. The deadly mix would measure 30 miles in diameter and burn everything in its path with 1,000-degree heat.

“When I saw the initial blast coming up out of where the mountain detached and growing right beneath our feet, I was convinced that this was it,” Stoffel said. “I did think of my mother, and I thought ‘I’m going to disappear, and she’s not going to know what happened to me. She didn’t know I was flying from Yakima. I’ll just be gone.’ ”

With no time to spare, the pilot took a nosedive to gain speed and try to outrun the explosion. Within seconds, the blast ripped off the top 1,300 feet of the volcano, producing a mushroom cloud that erupted 65,000 feet into the air.

“We could actually see into the crater at that point, what is now that huge amphitheater with walls as tall as the Grand Canyon, and we saw that morphology change just within moments,” Stoffel said.

Grasping the need to escape the 600 mph blast, the pilot flew south to Portland instead of northeast, back to Yakima. His split-second decisions saved all three passengers’ lives. When the pilot finally cut the engine on the tarmac, Stoffel jumped out of the plane and started running.

“I begin to recognize that Keith and Bruce are running with me. … We are all nonverbal, just running,” Stoffel said, chuckling. “We get to the terminal, and then we realize we’ve left my purse and our cameras on the plane. We looked out on the tarmac, and there is our little plane with the doors wide open.”

To learn more about the rest of Dorothy Stoffel’s story and others’ local perspectives, or to add to your own memories, visit the MAC at 2316 W. First Ave., open Tuesdays through Sundays from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Individuals can also submit memories online, at https:// mshcriticalmemory.org/.

“The ‘Mount St. Helens Critical Memory’ exhibit will be a hands-on, interactive experience, so people’s personal stories can be part of the narrative of the exhibit,” Liggett said. “This weekend we will be opening up our crowdsourcing site where you will be able to access our portal through the museum’s webpage on the exhibit and where you can upload pictures, stories, memories.”

This localized exhibit of the community’s recollections will run concurrently with another volcano-centric exhibition upcoming at the MAC: “Pompeii: The Immortal City,” which opens Feb. 7. That show will bring to life the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.