Washington, Idaho colleges bracing for ‘enrollment cliff’ in 2025

For colleges and universities across the United States, the Great Recession was a punch in the gut. Among other challenges, the financial crisis resulted in steep declines in state funding, forcing public schools to drive up tuition.

Now many schools are bracing to be hit again.

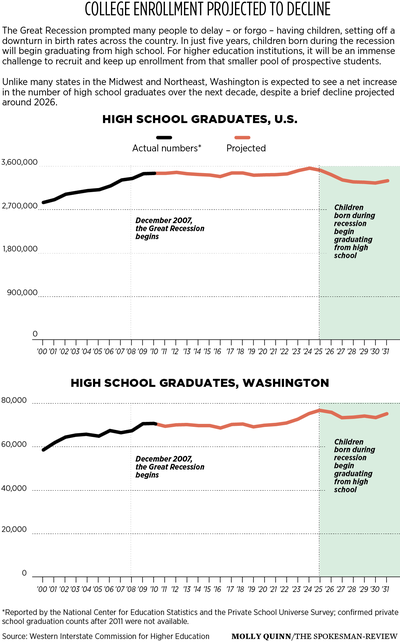

That’s because the recession didn’t just cost people their homes and jobs. It also prompted many to delay – or forgo – having children, setting off a downturn in birth rates across the country.

In just five years, children born during the recession will begin graduating from high school. For higher-education institutions, it will be an immense challenge to recruit and keep up enrollment from that smaller pool of prospective students.

“The Enrollment Cliff of 2025. It has one of those ominous titles,” said Greg Stevens, chief strategy officer for the Community Colleges of Spokane.

Of course, the total number of recent high school graduates is only one factor in college enrollment. Schools also must consider the economy, demand for various academic programs, immigration and interstate migration trends, and support systems that keep students from dropping out.

“A lot of things impact whether high school students – no matter how many of them there are each year – are going to go on to higher education or not,” Stevens said.

In some regions, college administrators are preparing for harsh realities. Some schools – particularly small liberal arts colleges in the Midwest and Northeast – foresee budget cuts, layoffs and the elimination of academic and extracurricular programs. Some might be forced to close.

“There is no argument: demographic change is reshaping the population of the United States in ways that raise challenges for higher education,” Nathan Grawe, an economics professor at Carleton College in Minnesota, wrote in his 2018 book, “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education.”

To address those challenges, schools must look beyond the demographic groups that have traditionally attended college and focus on attracting students of color, low-income students and those pursuing higher education as older adults, said Mamie Voight, vice president of policy research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy in Washington, D.C.

“The white, upper-income, college-going population is kind of tapped out, and so any additional enrollment growth should be coming from a more broad array of students,” Voight said.

Schools in the Inland Northwest – including some that already are struggling to balance their budgets – are adjusting their recruitment strategies accordingly.

The University of Idaho, for example, hopes to draw in more older adults, including those who never attended college, those seeking to enhance their job skills and those looking to switch careers.

Eastern Washington University is focusing its recruiting efforts on Hispanic and Latino students, who are underrepresented at many institutions even though they belong to one of the fastest-growing segments of the U.S. population.

And Gonzaga University has decided to stop recruiting in the Midwest and boost its marketing efforts in states like Utah, Arizona and Washington, which are expected to produce relatively high numbers of high school graduates in the coming years.

“We’re keeping an eye on those areas where growth might occur in the next decade,” said Julie McCulloh, Gonzaga’s associate provost for enrollment management. “We’re trying to be very aware of the changing demographic and business requirements.”

Phil Weiler, a spokesman for Washington State University, noted that Washington receives many transplants from other states and is expected to see a net increase in the number of high school graduates over the next decade. That’s despite a brief decline projected around 2026.

Weiler said in an email that “we will see increased competition for Washington students from out-of-state schools, but our in-state pipeline looks much better than many other states.”

Dean Kahler, UI’s vice provost for strategic enrollment management, struck a similarly optimistic note, though he also anticipates heightened competition among schools in neighboring states.

“We’re certainly going to be very sensitive to this because we recruit in more than just Idaho,” Kahler said. “But there’s a lot of states that are going to be hit a lot harder than our state is.”

Births signal enrollment decline

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the annual number of live births in the country plummeted from a peak of 4.32 million in 2007, the year the recession hit, to 3.93 million in 2013 – a decline of about 9%.

After rising slightly, birth rates recently took another downturn. About 3.79 million babies were born in 2018 – the lowest number in 32 years, according to the CDC.

To plan for the future, many colleges and universities rely on high school graduation projections from the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, a consortium of public college systems in 15 states.

In its most recent “Knocking at the College Door” report, WICHE used data from the National Center for Education Statistics and a survey of private schools to create state-by-state high school graduation forecasts.

“By 2030,” the report states, “the annual number of public high school graduates is expected to decline by about 120,000 compared with 2013.”

That 4% decrease is primarily the result of the decline in birth rates, according to the report.

Over the next decade, WICHE projects that New Hampshire will see the steepest decline in high school graduates, losing about 17.8%. California is expected to lose 8% during that same period, while Oregon will lose 2.5% and Arizona will lose 10.3%.

Washington, meanwhile, will see a 7.4% increase in high school graduates, while Idaho will gain 5.1%, according to WICHE.

Weiler, the WSU spokesman, also pointed to forecasts from Washington’s Office of Financial Management that show the state will gain more than 60,000 people ages 17 to 22 through 2030.

Those forecasts, however, don’t capture the likelihood that high school graduates will attend college.

Using studies from the Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics, Grawe, the economist at Carleton College, predicted that states like Arizona and New Mexico will see the biggest increases in college attendance, while the biggest decreases will be felt along the East Coast.

Grawe’s model, which he dubbed the Higher Education Demand Index, indicates that elite and top-ranked schools will be somewhat insulated from the enrollment cliff, while two-year and regional colleges will be most affected by population declines.

That doesn’t necessarily spell doom for schools in the Inland Northwest, however. In an email, Grawe said many community and regional colleges “have so penetrated the market that the demand for these higher ed markets follow that of the population.”

Colleges facing budget shortfalls

Several schools in the region already have struggled to balance their budgets in recent years. The root causes are varied.

EWU, which has struggled to meet enrollment targets, is undergoing a major reorganization to eliminate a budget shortfall of more than $3.5 million. Some tenured faculty members have taken buyouts, and administrators are working on a plan to merge EWU’s seven colleges into four.

The reorganization has ruffled some employees, including faculty members who oppose making the EWU library a subunit of one of the colleges. “We cannot support a plan that will yield little cost savings while greatly harming our future ability to serve the students, faculty and staff of Eastern Washington University,” library faculty said in a recent letter to administrators.

Declining enrollment is sometimes attributed to a strong economy: When jobs are readily available, people might choose to work instead of going back to school.

But EWU also struggles to retain students. Among degree-seeking students who began their studies at EWU in fall 2012, only 44% graduated within six years, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. The national average for public four-year universities is 60%.

WSU, meanwhile, recently announced it’s back in the black after eliminating a $30 million deficit in its main operating budget, although the school’s athletics department continues to overspend. Among other belt-tightening measures, each university department was ordered to trim its budget by 2.5%.

Before Kirk Schulz took over as president in 2016, WSU had nearly depleted a reserve fund that once topped $120 million, investing heavily in projects like the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine in Spokane and a branch campus in Everett.

And across the border in Moscow, UI is offering buyouts and voluntary employee furloughs to address a budget shortfall that’s projected to reach $22 million by 2022.

Waning enrollment and tuition revenue are part of the problem, while other factors are beyond UI’s control. Idaho Gov. Brad Little recently ordered most state agencies to trim their budgets by 1%, and the state Board of Education directed universities to earmark a larger share of their reserves for employee pensions.

UI spokeswoman Jodi Walker said the university needs more money from the state to stay afloat.

“Our support from the Legislature certainly has decreased over the years,” Walker said. “It has bounced back a little bit from the recession, but it’s certainly not back to where it was before.”

Nationally, state disinvestment is the biggest financial problem for public colleges and universities, said Voight, with the Institute for Higher Education Policy.

Twenty years ago, Voight said, states covered more than two-thirds of the cost of public higher education, while student tuition covered the rest.

“Now, using 2018 data, we see that it’s almost a 50-50 split,” she said. “That is really leading to a lot of the challenges we see in terms of affordability for students, as well as pressures on institutions to try to make ends meet as they try to avoid raising tuition on students.”

Washington lawmakers have taken steps to close the gap. In 2015, Republicans led an effort to cap tuition rates and “backfill” university coffers with state money. And last spring, Democrats pushed through a major expansion of the State Need Grant that covers the full cost of tuition for students near the poverty line.

Adjusted for inflation, Washington’s spending fell $1,388 per student between 2008 and 2017, a 15% decline, according to a study from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. In Idaho, state spending fell $2,012 per student, or 18.6%, the study found.

Private colleges don’t get operating funds from the state, though they do have large endowments and can raise tuition at will.

Greg Orwig, vice president of admissions and financial aid at Whitworth University, said enrollment at the school has been stable in recent years. In fall 2018, the school had 2,370 undergraduates and 406 graduate students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

As the WICHE report forecasts, Orwig anticipates about four more years of high school graduation growth before the enrollment cliff.

“I would say we are financially as healthy as we’ve ever been,” Orwig said. “But … because we remain a largely tuition-driven institution, that strength and stability is vulnerable to the larger demographic and economic trends.”

Strategies and solutions

In fall 2018, about 16% of EWU’s undergraduate students were Hispanic or Latino, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Within a few years, President Mary Cullinan hopes to increase that representation to at least 25% – a threshold that would qualify EWU for a federal designation as a Hispanic-serving institution.

“If you become an HSI, you are eligible for tremendous amounts of federal support grants,” Cullinan said in an interview last month. “It could even double the amount of grant money that we get.”

To meet that goal, Cullinan said, EWU hopes to draw in transfer students from Yakima Valley College and Columbia Basin College in Pasco, where the student bodies are 55% and 39% Hispanic, respectively.

College attendance rates among Hispanics have soared in recent decades, as has their representation on college campuses. Systemic disparities persist, however, leading Hispanic students to graduate at lower rates than white students.

Cullinan said the HSI designation would enable EWU to better serve Hispanic students who are the first in their families to attend college.

Jim Perez, a former college administrator who’s working on the initiative as a consultant for EWU, added that any HSI grant funds would benefit the whole university.

“That money will be designated for the entire student population, not just for Hispanic students,” Perez said.

“Quite frankly, Eastern, like some of the other colleges, are struggling to maintain their enrollment goals,” he said. “So we see this as an opportunity to achieve multiple goals with one initiative.”

To reach its enrollment goals, UI recently rejoined the Western Undergraduate Exchange, a scholarship program run by WICHE that offsets out-of-state tuition costs for students in participating states, said Kahler, the vice provost. That means fewer out-of-state students are paying full tuition, yet fewer are driven away by a high sticker price.

“If we were able to bring in all of our non-residents at the non-resident price tag, yeah, that would help our budget tremendously,” Kahler said. “But the reality is that price point is a super sensitive thing for our consumers now, and they just are going to schools where the price point is more attractive.”

UI administrators also are looking beyond the typical pool of recent high school graduates and considering ways to serve older adults. That coincides with a broader push in higher education to offer practical, skill-based certificates alongside two- and four-year degrees.

A few credit hours in computer coding, for example, might be useful to mid-career adults seeking to update their job skills or polish their résumés, Kahler said.

“I think higher education is really diversifying in the portfolio that we’re offering,” he said.