WSU Nursing College at 50: From humble beginnings to 21st century care

They filed two-by-two into the auditorium of historic downtown Riverside Place in Spokane on Thursday evening, joining the ranks of a club that’s a half century in the making.

Some of the graduates of Washington State University’s College of Nursing were drawn to the field by parents or grandparents who were nurses themselves. Others, like Riley Joyce, had a chance encounter with a nurse that sparked a desire to enter the field.

“I was in the hospital for almost four weeks,” said Joyce, who at 15 had complications from surgery and formed a bond with her night-shift nurse during her unexpected stay. “You’re so young, and you’re so embarrassed. She was just so calm about everything.”

The nursing students walking the stage at this fall’s commencement for the school do so on the 50th anniversary of its first class. Initially a partnership between four area colleges, the program has grown from a class of 37 to nearly 650 undergraduates statewide and many more graduate students who will push the profession into the future..

That group now includes Molly Henderson, another fall 2019 graduate who said WSU’s reputation would serve her well trying to find employment in an in-demand field.

“They’re really well known within the hospitals, as well,” Henderson said. “They have a really good relationships with the nurses and the staff because they’ve been here for so long.”

WSU nursing college began in a historic Spokane building with a first-of-its-kind agreement between multiple schools hoping to prepare nurses for a segment of health care primed for change.

Opening in the Carnegie Library on the western edge of downtown Spokane in 1969, the school moved to its $34.6 million headquarters in Spokane’s University District a decade ago, with other campuses in the Tri-Cities, Vancouver, Yakima and Walla Walla. Much of the job of training students to become nurses has remained the same, with candidates finishing their first two years of undergraduate coursework before applying for a spot at the regional instruction center for their junior and senior years.

“We do different things in the classroom now, in terms of helping the students learn better so they can pass the national licensing exam at the end of their four years,” said Mel Haberman, who was a student in the nursing college’s first class and now serves as its interim dean.

But the general process of pairing students with mentors and training in the community hasn’t changed, he said. What has changed is the technology available to aid instruction.

Some of the procedures once taught in clinics and hospitals throughout the Inland Northwest are now part of a simulation program, using highly sophisticated mannequins in controlled settings to mimic patient experiences that are rare. The school also is looking to adapt its curriculum to challenge the traditional role of the nurse as a responder to health crises, instead of a partner who can prevent problems before a hospital visit.

Nursing students at Whitworth in 1972. (WSU COLLEGE OF NURSING / Courtesy)

The new kids on the block

Haberman was sitting in the offices of Director Hilda Roberts and facing deployment to Vietnam when he first heard about WSU’s bachelor’s program in nursing.

“I went to all of the recruiters in town, and saw that the best they could do for me was to be a combat medic, which I didn’t want to be, since they were the ones killed the most in Vietnam, along with the radiomen,” Haberman said. “I started looking on campus, and heard there was a nursing program.”

As luck would have it, he found out in Roberts’ office on top of the university’s athletic building in Pullman, the deadline for applying for the new program was that same day. Haberman applied, and now, more than 50 years later, he’s the interim dean of the college and a distinguished professor in geriatrics, with a career spent focusing on care for cancer survivors.

Haberman was one in a first class of 37, which included five men. The enrollment allowed him to be in the Army Nurse Program, which required him to serve three years in the branch’s Nurse Corps.

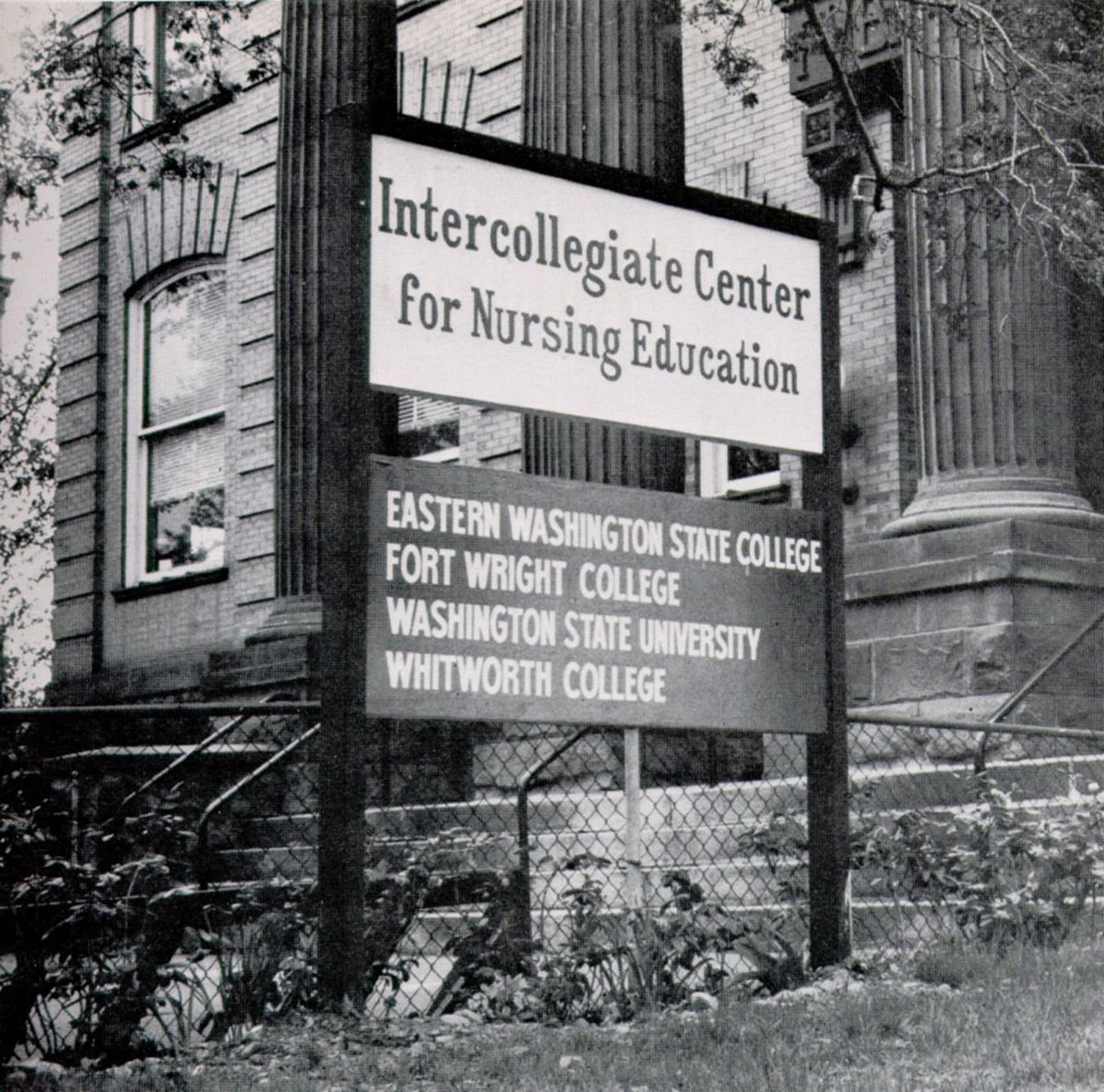

He was stationed in El Paso, Texas, once he’d completed his coursework at what was then known as the Intercollegiate Center for Nursing Education.

It was called that because WSU had partnered with Eastern Washington State College, Whitworth College and Fort Wright College to establish the training center. The colleges were responding to national studies in the mid-1960s indicating the number of nurses with bachelor’s degrees was well behind what would be necessary for instruction of new nurses by the end of the decade.

That prompted the first push for nurses to attain academic degrees beyond the certifications offered at diploma schools in area hospitals, with members of the American Nursing Association in 1965 calling for a minimum bachelor’s degree for all practicing, professional nurses.

“In the nursing field changes have been in the wind for many years but gained impetus in 1965 when the American Nurses’ Association issued a position paper recommending nursing degrees be granted by institutions of higher learning,” Lillian DeYoung, the college’s coordinator of curriculum, told The Spokesman-Review in 1972.

Whitworth, WSU and Gonzaga University had previously established bachelor’s degree programs for nurses, but those programs had been discontinued for various reasons, including funding concerns. That left just the diploma programs run by area hospitals.

Haberman said he remembered performing clinic hours with nurses at Sacred Heart Medical Center in the early 1970s when it was announced the hospital would no longer offer a diploma program.

“The majority of nurses had been graduated from that program,” Haberman said. “So there was some, I think, indirect frustration. We were sort of like, the new kids on the block, and it was awkward to be there the night they announced the program was closing.”

Students still perform those clinical hours, and end their studies with a practicum in which they are paired with a professional nurse for a month ahead of graduation. Chantelle Williams completed her practicum in labor and delivery at Providence Holy Family Hospital in Spokane, a concentration she’d like to enter after her graduation this fall.

“We just basically do their job, while they sit back and watch us and monitor us,” said Williams, who said she’ll be the first in her family to receive a bachelor’s degree and the family’s first nurse. The Kent, Washington, native transferred to WSU after completing her prerequisite courses at San Francisco State University.

There were so few students in the first class that all prospective nurses progressed through the curriculum together. But the program quickly grew, numbering 200 students by 1973, when Sacred Heart’s diploma program graduated its final class. The budget grew from just $44,735 in the first year to $1.5 million a decade later.

The school grew too big for the old library and its gray walls and fireplaces. In 1980, the Magnuson building opened near Spokane Falls Community College and would house the training program for the next 29 years.

Haberman taught for a year at the new building, then left for posts in Western Washington. He returned in 1999, after obtaining master’s and doctorate degrees from the University of Washington, and was named interim dean earlier this year.

It’s not a post he thought he’d occupy all those years ago, sitting in Roberts’ office.

“I sort of followed the wave of advanced education for nurses,” Haberman said.

That wave has been breaking in different ways over the past 10 to 15 years, as the college has moved into a new headquarters on downtown Spokane’s eastern border, while new technology and growing numbers of students have pushed much of the instruction back into the classroom.

‘The door is closed, and they’re in here working as a nurse’

Kevin Stevens’ second-floor laboratory is a corridor of medical devices, hospital beds and lifelike limbs.

But it’s the room at the end of the hallway that is the piece de resistance of her lab.

“When she’s on, you’ll see her blinking,” said Stevens, director of the college’s simulation program, hitting the “on” switch on a $75,000 high-fidelity mannequin wearing a silver-toned wig and spectacles. “You’ll see her chest rise and fall, just like she’s breathing. She’s got heart and lung sounds, just like you and I have them.”

Jesse Tinsley

Heaven forbid one of Stevens’ students refer to the lifelike body in the hospital bed before them as “a dummy.” This highly complicated medical device, attached to a computer controlling behaviors that can include sweating, bleeding and crying out in pain, is now a player in the proving ground for upperclassmen hoping to earn their nursing certification.

Stevens arrived at WSU by way of Fairchild Air Force Base in 2010, and brought with her a dedication to teaching nursing through simulation. Students enter an exam room that mirrors those at any regional hospital and are assigned a series of tasks they must complete, with Stevens or one of her assistants providing real-time feedback.

The method requires buy-in from the students, something Stevens said has grown with time, and also nationwide research that showed up to half of a nurse’s instruction can be achieved through simulation without a hit to test scores.

“The door is closed, and they’re in here working as a nurse,” she said.

The benefits of simulation, which would have been impossible with the technology available when the school opened its doors in the 1960s, is that instructors have control over the types of scenarios students face. They can present nursing candidates with conditions they would be unlikely to see completing clinic hours in area health centers and hospitals, Stevens said, or that new health regulations would prevent them from performing before completing their training.

“It’s focused learning,” Stevens said. “We know that every student that graduates out of our program will have had an opportunity to participate in at least two code scenarios.”

“Code scenarios” is health care-speak for cardiac arrest.

Cassidy Gurich, who can now add “B.S.N.” to the end of her name after graduating this fall, said that simulation exercise prepared her for clinical work when she did see a patient whose heart stopped.

“I learned the more serious you took it, as like a real situation, the more you could learn from it,” said Gurich, whose training helped prepare her to select the proper medicine for her heart attack patient.

“I would have been freaking out, if I didn’t know what to do,” she said.

The other benefit to performing hundreds of hours of simulation on a campus is that the school doesn’t have to go looking for additional clinical partners, which can be hard to find in far-flung areas of Eastern Washington and with high demand from other learning institutions, said Haberman, the interim dean.

“The clinical placements are saturated, because we have so many nursing schools,” he said. “And the online classes that we have, out of Washington state, are enrolling students and all fighting for the same clinical spaces.”

Even so, WSU’s nursing college has students in more than 600 locations performing on-the-job training, he said. The number of potential locations for nursing students at the college totals 2,500, many of them in rural centers that reflect the ongoing commitment to provide care in underserved areas. That commitment was made in the early days of the school.

“I hope the new training will encourage many to go to areas where few health personnel are available but are badly needed,” DeYoung, the school’s curriculum coordinator, told The Spokesman-Review in 1972.

Simulation doesn’t just instruct the technical skills required to become a nurse, Stevens said. Faculty can speak to a student through a microphone and run through sophisticated scripts to deal with a number of health issues, both physical and emotional.

It’s this type of training that will push the nursing profession forward, said Lisa Day, associate dean for academic affairs at the college.

What’s old is new again

For generations, nursing instruction has been focused on preparing students to work in hospitals and deal with the fallout of health crises, Day insists.

“These programs have been sort of stuck in an old way of training by loading up content,” she said. “Putting tubes in, taking tubes out – that’s what we’ve been focusing on.”

The University of California, San Francisco-educated administrator said it’s time to do something new. Or perhaps even older.

“If you look at the further back history of nursing, this is sort of where nursing began, is in public health,” she said. “Really trying to create environments that are healthy for people to live in.”

Instead of placing aspiring nurses in assisted care facilities and hospitals, where they’re dealing with patients who are already experiencing health problems, Day envisions a future in which nursing students instead visit regional health centers and health fairs, interacting with healthy people before they’re at-risk of admission.

“It’s not that we’re saying there’s no place for RNs in hospital environments, because there definitely is and there definitely will continue to be,” Day said. “I think that part of what’s going to shift this focus of health care, is when we shift the focus of our education to help these new nurses to see the possibilities they have outside of hospital-based rescue.”

The idea actually hearkens back to the work of Florence Nightingale, the 19th century British social reformer credited with professionalizing the industry for women in her care for soldiers. After the death of a lower-class laborer in a London workhouse in 1864, Nightingale wrote a report to Parliament calling for changes to the treatment of illness among the city’s working poor, including the creation of a taxpayer-funded medical relief fund for workers.

Day sees the education of modern nurses following in those footsteps, preparing graduates to push for public policy changes and take an active role alongside doctors in developing treatment and prevention plans with patients seeking primary care. That will require a shift, as well, in public perceptions of what nurses do, she said.

“We hear, all the time, that nursing is the most trusted profession,” Day said. “I wonder what that really means, that we’re the most trusted profession. If you read most of what’s published in the popular press, it refers to doctors, MDs.”

Some of that work is already occurring. Taylor Bye, a 2019 graduate of the school, said his clinical experience included work with the Spokane Fire Department and their Community Assistance Response, or CARES, Team. That group visits frequent 911 callers who are experiencing chronic medical conditions and have no insurance to cover traditional care.

“It was a really good experience,” said Bye. “Those are more about preventing emergencies. It’s like, you’re trying to limit as many medical emergencies as you can.”

Day pointed to other nursing schools, including regional players like Seattle University and the University of Washington, as already adopting this type of instruction early in the curriculum. That includes education on things like motivational interviewing, which allows nurses to work with patients in determining potential health problems, rather than simply putting on a blood pressure cuff and writing down vital-sign observations.

This curriculum reform is intended to continue to push the WSU nursing college’s instruction into the next 50 years, just as the decision in the 1960s to provide an in-demand academic degree for the profession spurred the creation of the school in the first place.

“I don’t recall any discussion that they thought this program was going to fail,” said Haberman, reflecting on his early years when the faculty numbered fewer than a dozen and accreditation wasn’t a certainty. “It wasn’t an experiment.”

Fifty years on, the legacy created from that initial program allows students like Gurich, who will also be the first nurse in her family after idolizing one who cared for her ailing grandfather, to pass that care on to a new generation of patients.

“Honestly, it’s been such a long journey, and I never thought I’d actually be a nurse,” she said. “It’s a dream come true.”