Research solves WWII mystery: Nephew’s book, ‘Not Forgotten,’ puts family’s questions to rest

Dave Reynolds never met his uncle, U.S. Army Cpl. Lester LaVerne (Verne) Zornes, but he’s never forgotten him.

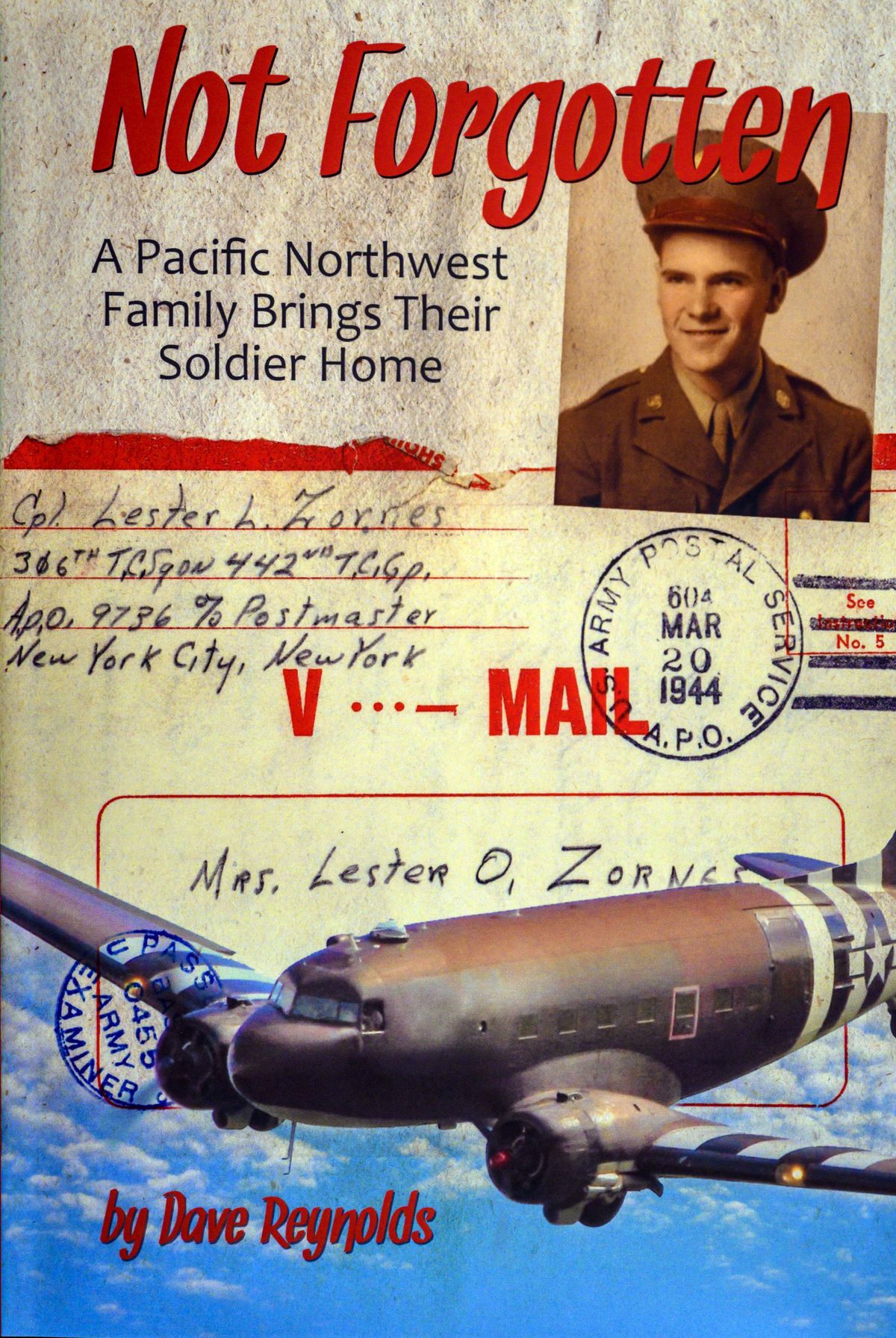

Now, thanks to Reynolds’ self-published book, “Not Forgotten: A Pacific Northwest Family Brings Their Soldier Home,” the rest of the world can get to know the 19-year-old Lewis and Clark High School graduate who died while serving in the Army Air Force during World War ll.

“I’d seen his photo on the wall at Grandma’s house above everything else, but nobody ever talked about him,” Reynolds said.

When he asked his mother about her oldest brother, she told him Verne was killed by friendly fire somewhere in Africa. When he asked his grandmother, she told him her son had been shot down by air pirates. And when Reynolds got in touch with an old friend of Verne’s, the friend told him his uncle’s plane had been engulfed in a sudden sandstorm and crashed.

The stories intrigued Reynolds and prompted him to search for answers to what really happened to his uncle.

He started asking questions in 1992, and the questions revealed that decades after her son’s death, his grandmother’s anger still burned white hot.

“It wasn’t right of the government to take my precious son, the greatest gift God ever gave a mother,” she said.

Other family members often smiled when remembering Verne.

“Everyone I talked to described him as a wonderful guy who loved to make people laugh,” Reynolds said. “It made me wish I could have known him.”

Records he received from the National Personnel Records Center show that Verne is buried in the North Africa American Cemetery in Tunisia.

“Why wasn’t he laid to rest in Spokane?” Reynolds wondered. “Why didn’t they ship his remains home? And how did he really die?”

The answer to the first question was revealed in correspondence between his grandparents and the military. It turns out the government had repeatedly offered to send Cpl. Zornes’ remains home, but his grandparents hadn’t accepted the offers.

“I think my grandparents were so devastated after he died, they didn’t know what to do. And maybe there was a certain amount of denial,’ Reynolds said.

Indeed. When his widowed grandmother, Minnie Zornes, moved from the home Verne had grown up in, she kept her white pages listing in her husband’s name.

“In case Verne comes home and tries to find us,” she said.

The records also revealed that none of the stories Reynolds had been told about his uncle’s death were true.

Reports from World War ll aviation crashes have been declassified and Reynolds was able to get a copy of the crash investigation, which included photos and eye-witness testimony from survivors. He learned his uncle, a radio operator, had died on March 22, 1944, in a plane crash that investigators deemed accidental.

“It was simply an accident — something I think would have been very hard for my grandmother to accept,” he said.

Over the years, Reynolds continued to piece together bits and pieces of his uncle’s life and untimely death. After his mother and grandmother died, he inherited a trunk filled with family photos and memorabilia.

When he discovered the cemetery in Tunisia would place flowers at his uncle’s grave and send a photo, he asked them to do so. He had an additional request.

“I asked them to place the words ‘You are not forgotten’ at the grave,” he said.

He was amazed when he received the photo and saw the date it had been taken — Nov. 30, 2013, exactly 70 years since the last time Verne’s family saw him.

They could have had his remains shipped home, but Verne had been moved several times in Africa, and his surviving sister and brother felt it was best to let him rest in peace.

In the course of his research, Reynolds found that though his uncle’s name had been omitted from the memorial at Lewis and Clark High School, he did have a flag that is flown every Memorial Day at Fairmount Memorial Park.

He decided to have a marker placed beneath the flag. On the 70th anniversary of Zornes’ death, a memorial service was held at Fairmount, including a joint honor guard ceremony from the Air Force and Army.

After the service, as he returned items to the trunk he’d inherited, Reynolds discovered an amazing treasure. Beneath the photos and other memorabilia lay a stash of his uncle’s letters concealed in paper bags.

“Sixty-six letters, a postcard and a government issued Mother’s Day card,” he said. “They’d been there all this time.”

He included the letters in “Not Forgotten: A Pacific Northwest Family Brings Their Soldier Home,” which he published in July.

“I didn’t set out to write a book,” Reynolds said. “I just wanted answers for myself and for my family.”

But Verne’s surviving brother and sister encouraged him to publish the story.

“They can finally talk about Verne. It’s offered some closure for them, and my uncle’s wife said that it could help other people.”

When asked what he thinks his grandmother’s reaction to the book might be, Reynolds smiled.

“I think she would be proud to know that people are finally getting to know her precious son,” he said. “He didn’t come home, but he’s not forgotten.”