Getting There: The how of ‘the Y’

The Division Y was paved and open to traffic in September 1932, the year this photo was taken. (Ferris Archives/Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture)

The Y.

Name any other intersection in Spokane that can be so easily known. Two syllables, four letters. Say it and the mind conjures many things: The end of the city. Endless traffic. Fast food. Vast parking lots serving big-box stores. The Bigfoot Pub & Eatery.

And now, beautiful new pavement.

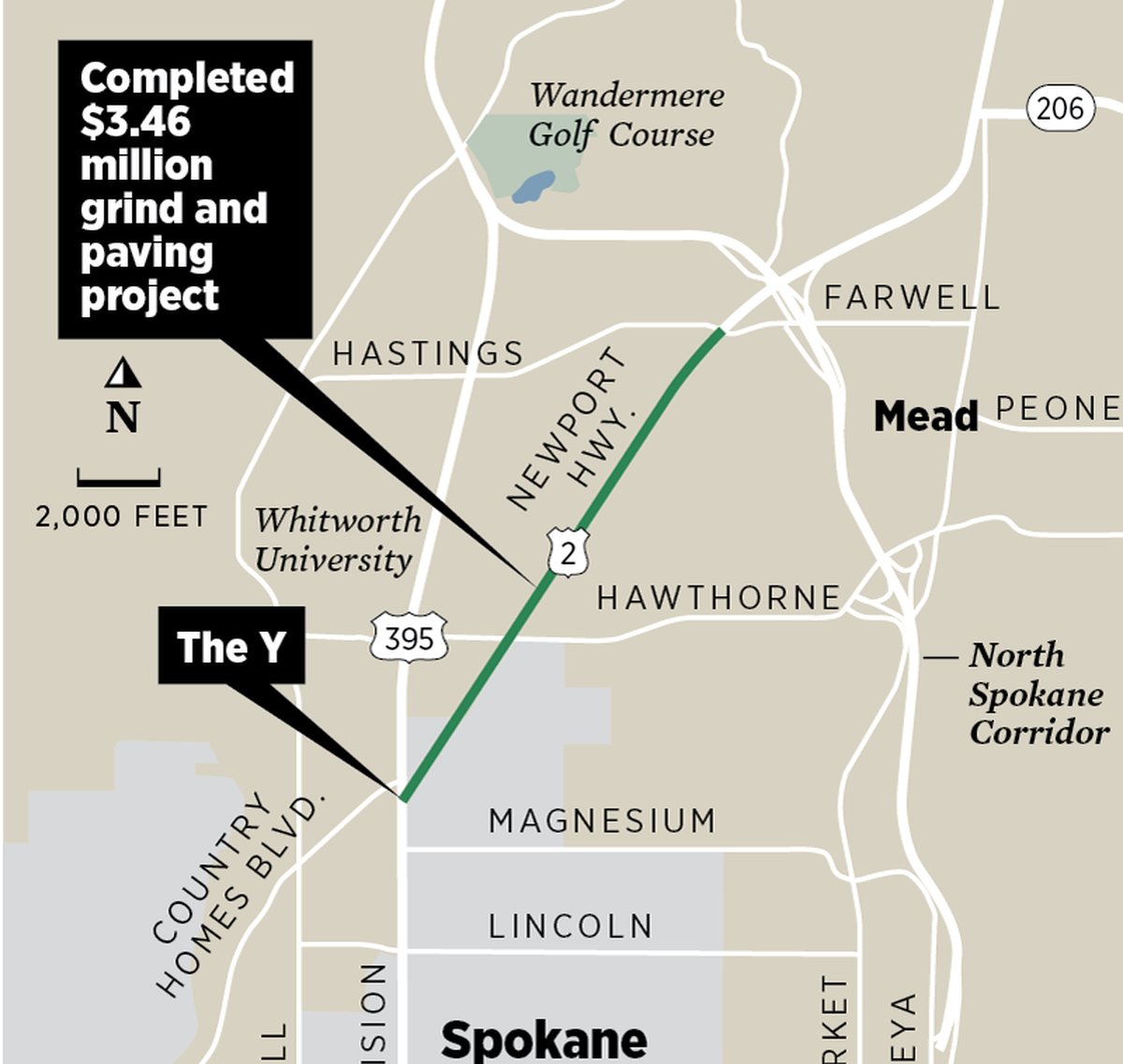

The Washington State Department of Transportation recently rehabilitated part of the Wye, as the state agency calls it. Work crews remade about 2.7 miles of its northeasterly arm, what’s officially called U.S. Highway 2 and occasionally called the North Newport Highway. The $3.46 million project ground down the old, broken and nasty surface and replaced it with new hot mix asphalt.

It’s the new pavement that will please motorists, but it’s anyone’s guess how many times the busy road has been repaved. Lots, considering the road saw an average of 24,000 vehicles a day in 2018. Underneath those onion-like layers of asphalt, however, is the first pavement. When it was laid, when the Y was first paved, is a chapter in the annals of American highway building.

But first, the story of the Pend Oreille Highway, the northeasterly arm of the Y.

The highway was designated as a state route in 1915 by the Legislature, which described it as “the most feasible route through the town of Mead to Newport in Pend Oreille county.” Lawmakers put aside some money to survey and construct the route.

Though not quite aligned the way we know it, the Y was born. The new state route intersected with the old Cottonwood Road, not much more than a primitive wagon road built by an army of volunteer laborers seeking to connect Spokane to Chewelah, “a distance of about 60 miles through the timber.”

At this point, the roads weren’t much more than rough routes to Spokane’s hinterlands, but the Y appeared on maps. A 1918 map of the U.S. – produced by the American Automobile Association held by the Library of Congress – clearly shows the Y. So does a Rand McNally and Co. map from 1920, also in the Library of Congress.

But the roads, though official and surveyed, remained primitive.

Then something happened that changed the country, a momentous event that most people probably take for granted: . The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921.

In his book about America’s superhighways, “The Big Roads,” Earl Swift describes the act as “the foundation for modern highway building in the United States; it remains the single most important piece of legislation in the creation of a national network – far more so than the later interstate highway bill, which would not have been possible, or necessary, without it.”

In short, the act created the nation-spanning system of roads we have today, and did this in part by saying that every county seat in the nation had to be connected by a network of well-paved roads. The person who led the charge for the bill – a road engineer from Iowa named Thomas MacDonald – is responsible for American highways as we know them. At the time, he led the federal Bureau of Public Roads, which later became the Federal Highway Administration.

The demand to connect every county outpost led to the paving of many roads, and that includes the roads of the Y, which connected the Pend Oreille County seat of Newport to Spokane County’s seat.

Another aspect of the bill that helped the Y come alive with pavement was its insistence that locals largely got to decide where roads went. The existence of the Spokane Regional Transportation Council is a direct descendant of the 1921 act, which said that states were the source of highway plans, while the federal government oversaw design, construction and maintenance standards.

We can credit MacDonald for laying the groundwork of the modern highway system, but he was simply reacting to a vast change in American transportation, as Swift details in his book.

In 1900, there were 8,000 cars in use in the entire country. By 1910, there were about 500,000. Six years later, there were 3.4 million. By 1920, almost eight in 10 of the world’s cars were operated by Americans. Government and its deliberative mechanisms were left behind by this widespread adoption of new technology, and they knew it. As the number of American drivers exploded, a U.S. State Department survey judged the country’s road conditions to be “far worse than any other major nation except Russia and China,” Swift wrote.

With the highway act, that would change, and Spokane was ready.

The route to Newport had been decided in 1915, but legislators continued to tinker. In 1923 – as federal officials waited for state highway officials to deliver their state maps before they could sew them together in a national system – state lawmakers gave the road a name.

“A primary state highway, to be known as State Road No. 6 or the Pend O’Reille Highway, is established as follows: Beginning at Spokane; thence by the most feasible route in a northeasterly direction to Newport in Pend O’Reille County; thence in a northerly direction through Metaline Falls to the international boundary line,” the legislative report read that year.

Boosters began to crow about the road’s attributes. The Spokesman-Review reprinted an entire speech given by “S. H. Anschell, Pend Oreille county land developer” that he gave to the “publicity-tourist bureau of the Chamber of Commerce” at the Davenport Hotel in August 1925.

Anschell described the highway as a “scenic route which can not be equaled anywhere.” He pressed them to act, as the hordes of motoring tourists were coming. “The tourist travel is increasing every year and it is now up to you to take advantage of this opportunity,” he said.

The following year, in 1926, the federal government printed a map it had been working on since the passage of the 1921 highway act, called simply the “United States System of Highways.”

To today’s eyes, it’s not that impressive. It’s just a nationwide road map, something every one of us probably saw as children. But in its time, when the word “road” loosely defined just about any path, it was revolutionary. And there, easily seen, is the Y. It’s a big Y, too, its tail starting in Colfax, splitting in Spokane, its arms stretching north toward Bonners Ferry, Idaho, and Grand Forks, British Columbia.

Years passed, however, and the intersection remained unpaved, but work crews inched closer and closer. In 1929, the Y’s tail, Division Street, was paved from the city core to Garland Avenue. North of there, it wasn’t. On Oct. 18, 1930, the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported that Division was finally paved with “two and three-fourths miles of concrete cement paving.” The pavement got closer to the Y, but stopped at Wellesley and went no farther north.

Two more years passed, and on Sept. 28, 1932, the paper reported on more concrete. This time the pavement went “north to connections with the Pend Oreille and Inland Empire highways.”

The Y, for the first time, was paved, and traffic began traveling on it on Sept. 29, 1932. Historic photos show its initial state: slabs of concrete, no painted lines, no sidewalks, no signals, no stores or billboards or traffic. Nothing. Just an acute angle of roads in the middle of sparse, undeveloped forest. And that’s how the area’s road boosters wanted it to stay.

The day after the roads opened, Frank Guilbert, the head of both the Inland Automobile Association and Eastern Washington Highway Association, said the Pend Oreille Highway should be kept free from development and billboards and be made a “model road way.” Everyone agreed, Guilbert said, and noted that the city’s sign companies pledged their cooperation to maintain the highway’s simple, natural beauty.

“No better spirit could be shown than that expressed by these firms in putting the plans for beautification of the highway ahead of their own interests,” he was quoted saying in the paper. “When this highway is developed into a beauty spot, it should be an encouragement to increase development of tree-planting along highways.”

Such vision is laughable now, considering how the Y has developed. The road builders came, and development followed. The trees are gone, and the road’s name has changed, but the Y remains.

In the city

A single lane closure of Spokane Falls Boulevard between Post and Monroe streets continues to hit commutes in downtown Spokane. It is anticipated to continue through August 23 from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. Main Avenue from Lincoln Street to Spokane Falls Boulevard, and Monroe from Main to Spokane Falls Boulevard will be closed to traffic. The work is related to construction of a large sewer and stormwater tank and public plaza.

Work on the first phase of the South Gorge Trail starts Monday. Clarke Avenue between Spruce Street and Riverside Avenue will be closed. This $3.5 million project includes construction of a 10-foot off-street trail, and pavement reconstruction on Clarke.

Basic chip-seal maintenance in the city’s neighborhoods will affect three locations. Crews will be working in the area bound by Lincoln Road to Vicksburg Avenue and Nevada Street to Antietam Drive; the area bound by Central to Rowan Avenue and Ash to Belt Street; and in the area bound by Ray to Regal Street and 33rd to 36th avenues.

Thirty-third Avenue remains closed from Bernard to Lamonte. The $1.3 million grind and overlay project will reconstruct the road’s pavement and replace sewer and water mains.

Erie Street remains closed from Trent to Denver. The $2.1 million project is building a stormwater facility and includes bio-infiltration swales and related drainage structures.

Five Mile Road remains closed between Lincoln and Strong roads. Cars are not permitted. The $2.7 million project is completely restoring the street’s pavement, and includes the installation of ADA ramps at intersections and crosswalks, replacement of an 18-inch steel water main, stormwater improvements including swales and trees, installation of pedestrian lighting at Five Mile and Strong Road and the installation of a roundabout at the intersection of Five Mile and Strong roads.