Summer Stories: ‘Many Crowns’ by S.M. Hulse

In the final month of her final summer working at Dairy Palace, Debbie Baker’s boss asked her to be the Dairy Princess in the end-of-summer parade. After three-and-a-half years of wearing a black-and-white cowhide-patterned paper crown while dispensing cone after cone of soft-serve every afternoon, it was finally her turn to wear a glittering tiara. After three years of following Sadie Johnson’s horse down the six-block parade route, pitchfork in hand, it was Debbie’s turn to ride and not worry about what her horse left in the road.

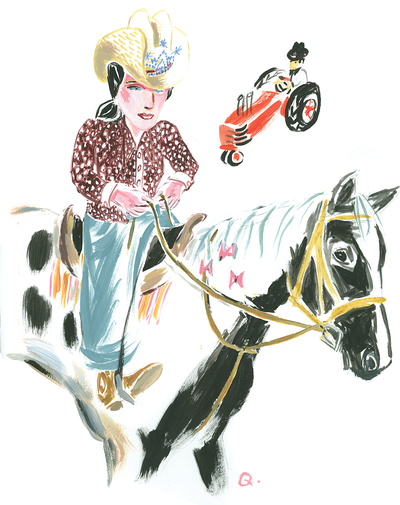

The request wasn’t a surprise – Sadie, a year older than Debbie, left for college last fall, and the other two Dairy Palace employees were boys – but Debbie grinned and thanked Mr. Shaw. Like most everyone in Tallwheat, Montana, her family attended the parade every year, and one of Debbie’s earliest memories was of she and her brother pushing their way to the front of the crowded sidewalk, competing to see who could catch the most candy thrown from the floats. The excitement of the Fourth of July had long worn off by the time the parade rolled around in late August, and folks poured in from the surrounding towns, eager for one last celebration before the weather turned crisp. They lined the short parade route and cheered enthusiastically for each of the parade entries, but never louder than for the Dairy Princess, who was always positioned right behind the leading banner and ahead of the mayor’s tractor. She smiled benevolently, waved elegantly, and handed out coupons for a free children’s cone with any purchase.

“That horse of yours is perfect,” Mr. Shaw told her. “Looks like a Holstein.”

Debbie assumed he meant that Domino, a piebald Paint, had the same coat pattern, not that his sturdy conformation resembled that of a cow. “We’ll make Dairy Palace proud,” Debbie said.

“I don’t doubt that,” Mr. Shaw said. “You’re my best employee.”

Suddenly Debbie glanced down at her skirt. She’d made it from her favorite pair of jeans and some scraps of calico. Her boots peeked from beneath the hem. “Um, Mr. Shaw?” She straightened the paper crown on her head. “It’s OK if I wear my split skirt in the parade, right?”

Sadie Johnson had always worn jeans. Debbie used to wear them, too, but six months ago her mother had decided that she and Debbie should only wear skirts or dresses. “The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man,” she’d quoted, “for all that do so are abomination unto the Lord thy God.” Debbie wasn’t sure about that, but she hadn’t minded much; she wore skirts to school and work most of the time anyway. But she’d always donned jeans to ride Domino, and she’d despaired until it occurred to her to suggest a split skirt to her mother. “Men don’t wear them,” she’d pointed out. “And Dale Evans had one.” Debbie was too young to remember much about “The Roy Rogers Show,” but her mother had always made time for it. Roy and Dale were good Christians. Now Debbie had two split skirts for riding.

“That’s fine, Debbie,” Mr. Shaw said. There was something troubled about the turn at the corner of his mouth, and Debbie wondered if he was remembering how earlier this summer he’d had to ask her mother to stop proselytizing in the Dairy Palace parking lot. “It’ll look right elegant, I’m sure.”

Debbie had Wednesday off, because she and her family had started attending midweek services a few months ago. Afterward, at dinner, her mother said she’d heard from one of the other women that Sadie Johnson had dropped out of college. She’d followed a boyfriend to California, where her parents had recently discovered her in an overcrowded house, doing drugs and what Debbie’s mother would only refer to as “other things.” Sadie’s parents tried to get her to come home with them, but she was 19 and they couldn’t make her.

Debbie’s mother was wearing a bandanna over her hair, the way she did when she cleaned house, but she usually only did that on Mondays. She’d worn one yesterday, too.

Debbie was sorry to hear about Sadie. She had been jealous of her for getting to be Dairy Princess so many times, yes, but Sadie had been nice to Debbie at work, and even loaned her a Glen Campbell record once.

“It’s a worrisome time,” Debbie’s mother said. “Especially for a girl on her own. It makes me wonder about Debbie going to Bozeman this fall. But you remember Sadie’s family hardly showed up at church last year. And I heard—”

“Don’t the Bible have something to say about gossip?” her father asked.

On the weekends Debbie rode the fence line with her father. He sold the last of the cattle in the spring, saying he wanted to concentrate on the feed store, but he kept up the pasture like it still housed Herefords. Debbie still hadn’t told her parents about the parade. Hadn’t told them that she wanted to double major, either, that she’d already written to the university about adding agriculture to her business studies, but she and her father never spoke on their rides. She just rode beside him and held Ace’s reins when her father dismounted to make an adjustment to the fence or pick up a piece of baling wire. Debbie understood the gesture for what it was. Ace ground-tied, so her father didn’t need her along to hold the horse.

Her mother was still wearing the bandanna a week later. While she was busy in the kitchen one morning, Debbie lifted the ribbon marking a page in her mother’s Bible. 1 Corinthians 11. But every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoreth her head. Most of the other women at their church wore skirts or dresses, but none covered their heads, certainly not with anything other than a hat, and only during services. Debbie even thought their pastor had said this was one of those culturally specific verses, that it was for the ancient church and not today.

“What are you going to do if she tells you to cover your head, too?” Debbie’s friend Anne asked.

“I don’t know.” They were whispering in an aisle of the five-and-dime downtown. Debbie held a bottle of bluing shampoo for Domino – so his whites would be bright for the parade – and a can of hairspray for herself. She handed them to Anne so she could study the lipsticks. She tried a few on the inside of her wrist, like she’d read about in magazines, and chose a pink a shade brighter than she was comfortable with. “Do you think the paper cow crown at Dairy Palace will count as a head covering?”

A week before the parade, and two weeks before Debbie was scheduled to leave for college, the Manson murders were plastered across the news. The way it dominated the talk Debbie overheard in the streets, and the way people wanted to discuss it while she handed them their cones and sundaes – Hard to believe a thing like that is possible, and, Can you even imagine? –reminded her of the way the moon landing colored conversations a few weeks ago, but that had been wonder. This was horror.

Maybe it was a desire to banish that shock and dread that made Debbie’s mother hand her a pink bandanna that evening. She had embroidered white flowers around the edge. Debbie had imagined arguing with her mother if this moment came, maybe putting forth the theory that long hair was a woman’s covering. But the little flowers were so perfect, so carefully stitched. And her mother’s hand was trembling. So Debbie thanked her and tied the bandanna over her hair.

And maybe it was a similar desire to change the mood in the house, to crowd out dismay with happier things, that led Debbie to finally tell her parents about being the Dairy Princess. “I’m going to wear my red paisley shirt and put red ribbons in Domino’s mane.”

Her mother stared across the dinner table. Her father looked at his plate of turkey.

“The Bible says women should ‘adorn themselves in modest apparel…not with broidered hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array’,” her mother said.

“I’ll wear my split skirt.” Debbie touched the bandanna on her head. “And my cowboy hat. The tiara goes over it, like a hatband. And the lipstick is just for show, like an actor wearing makeup in a play.”

Her mother’s eyes widened. “When did you buy lipstick?”

“It’s just the summer parade. It’s for fun.”

“Have you any idea how often evil gets a foothold because of things people think are for fun?” Her mother swept a hand over the table, just missing the gravy boat. “Look at the news, Debbie! Look at what’s happening in this world!” She put her napkin beside her plate. “In fact, I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to go to college this year. It’s too dangerous.”

Debbie gasped. “I leave in two weeks.”

“It’s better for you to stay home. You can keep working at Dairy Palace. Or help your father at the feed store.”

“I’m going to college so I can help Dad,” Debbie insisted. “I’m going to study agriculture as well as business. So we can make the feed store even better. So we can get more cattle.”

“That’s no program of study for a woman, Debbie. And just look at what happened to Sadie Johnson—”

“I’m not Sadie, Mom! I’m Debbie. I’m not going to go looking for trouble. And if it finds me anyway, it won’t be because you or I didn’t follow enough rules. That’s not how God works.”

“Deborah Rachel Baker, you listen to—”

“Davy didn’t die because you weren’t a good enough Christian, Mom. He died because his helicopter got shot down.”

Silence.

Debbie wanted to say her brother’s name again. She hadn’t heard it since the day in January when they got the news. Her mother sat opposite, looking at the uneaten meal on her plate. Debbie waited for her to yell, or cry, but her lips stayed closed, steady.

“I skipped church that Sunday,” her mother said at last. “And the soldiers came to the door the next day.”

“It wasn’t because you skipped church, Mom. It wasn’t anything you did. It just … was.”

More silence.

After a minute her father picked up his fork. “Davy always loved that parade,” he said.

The parade was everything Debbie had hoped it would be. The sidewalks were crowded, and people clapped and cheered as she rode by. She’d skipped the lipstick, but Domino arched his neck as if to show off his braided ribbons, and the tiara on Debbie’s hat sparkled in the sun.

Her father stood in front of his feed store. His arms were crossed, but he lifted two fingers in a small wave as she and Domino passed. Her mother was at home. She wasn’t ready to come to the parade. Wasn’t ready for Debbie to leave for college next week. But this morning she’d curled Debbie’s hair. “You’re the most beautiful Dairy Princess this town has ever seen,” her mother told her. “And I was one once, you know.”

Debbie guided Domino along the parade route. She smiled. She waved. She handed out coupons for a free kid’s cone with any purchase.