More than a viral sensation, the Salmon Cannon could bring the species back to the Upper Columbia after 90 years

Over the weekend, a 2014 video of a salmon being shot through a thin, flexible tube went viral.

Memes appeared imagining what the fish were thinking and feeling as they passed through the Salmon Cannon, as the salmon-propelling tube is known. On “The Late Show,” Stephen Colbert wondered if the tube’s inventors considered naming the device the Bass Blaster. The New Yorker wrote, non-ironically, about the “nihilistic euphoria of the fish tube.”

But, as internet hot flashes do, the excitement died down and the hordes dissipated, leaving a far more interesting – and important – story behind.

The Salmon Cannon, born in the apple fields of Eastern Washington, is a key component of the Colville Confederated Tribes’ plans to reintroduce salmon to the Upper Columbia River and, eventually, the Spokane River.

Swim, slide and glide

The Salmon Cannon is made by Seattle-based Whooshh Innovations.

The principal is simple: The tube, which is a proprietary plastic mix and very smooth on the inside, molds to the body of each fish that swims into it. Misters, placed on the outside of the tube, further lubricate the interior with water and allow the fish to breath. Then, an air blower pressurizes the space from below, pushing the salmon up at speeds that can reach 20 mph, much like a pneumatic bank tube.

“From the fish’s perspective, it’s swim in, slide and glide,” said Vincent Bryan III, CEO of Whooshh Innovations.

The system doesn’t hurt the fish and causes them little to no stress, according to multiple studies. In fact, some research indicates that the system saves the salmon so much energy that they are more likely to survive the long swim back to their spawning grounds.

The delicacy of the entire mechanized operation is a reflection of the invention’s birth in the apple industry.

While Bryan grew up in the Seattle area, his family owns orchard land in Eastern Washington. After graduating from law school at Seattle University, Bryan worked in international law and eventually found a job with Adobe in Seattle. But by 2004, he was growing tired of the work and took a sabbatical. During that time, he got more involved in the family business and, spurred partially by immigration-related labor shortages, started to wonder if there were a more “efficient” and mechanized way to pick apples.

To find out, he quit Adobe and started a company that invented machinery that could quickly and gently pick apples from trees. He got millions in seed money from an agriculture manufacturing company and made progress on his apple-picking technology.

But in 2011, he got distracted from his original mission after seeing a helicopter and being told it was carrying salmon over an otherwise impassable dam.

That, he thought at the time, must be expensive. And inefficient.

He’d grown up fishing and had always “been passionate about fish,” so he looked at some of equipment he’d designed to transport apples and, in particular, at a tube filled with cushioning material and thought, Why not fish?

To test his suspicion that the technology might translate, he went to a fish market in Seattle, bought live tilapia and fed them into a tube originally designed for apples.

“The tilapia seemed happy,” he said.

Like that, Whooshh Innovations was born.

What about dams?

Bryan saw that the technology could help solve one of the thornier barriers to restoring salmon in the Columbia River and to boosting other struggling salmon populations: dams.

Dams, even those with fish ladders, decimate salmon populations, as the fish make long upstream journeys to the spawning beds in which they were born in order to reproduce.

Dams without ladders, like Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee, are 100% deadly. Since 1930, when Grand Coulee was built, the salmon runs – once an annual bounty relied upon by native peoples – disappeared almost overnight.

The Salmon Cannon hopes to offer fish a detour, by transporting them up and over the dam through a tube.

But, as some pointed out after the technology’s surge of online popularity over the weekend, the technology only addresses a single symptom of larger problems facing the species.

“Salmon cannons have their purpose to get over some dams that don’t have fish ladders,” said Sam Mace, the Inland Northwest director of Save Our Wild Salmon in an email. “But they aren’t a solution on dams like the lower Snake, that have fish ladders and where the larger problem is the smolts having to get downstream, dealing both with the dams themselves and the hot water conditions, slow migration, and predator problems created by reservoirs.”

But the Snake River and the main stem of the Columbia are different systems with different challenges.

As Mace points out, “Smolts die in the Columbia reservoirs too, but the conditions are better. The temps don’t get as high on the Columbia. With the Snake running through such hot desert country, temps get over 80 degrees at Ice Harbor frequently.”

Bryan doesn’t believe that wholesale dam removal is a viable path forward, because “we also need the clean energy that those dams produce.” But he doesn’t dismiss the other problems caused by dams. Instead, he said, the technology developed by Whooshh could help address those problems, namely predation and heat stress.

Which, oddly, brings us back to apples.

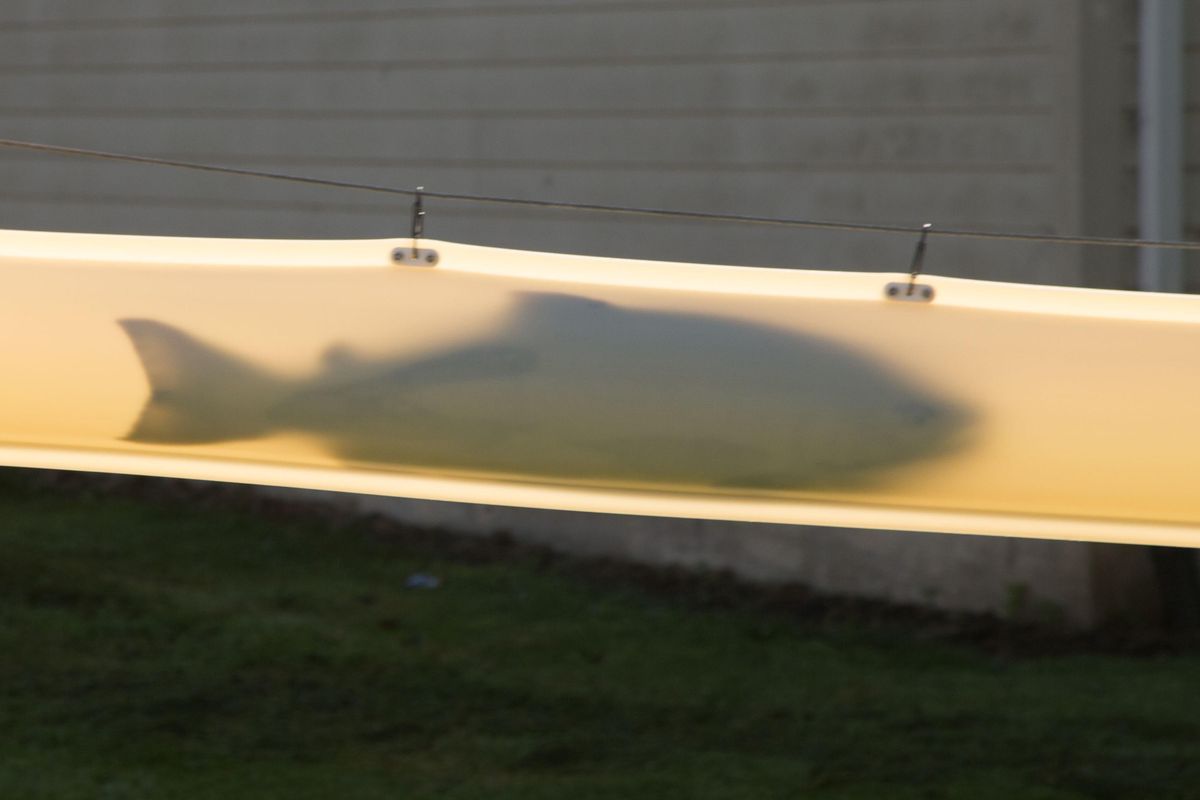

Chinnok in a tube. (Whooshh Innovations / Courtesy)

Salmon of my eye?

If you buy an apple at the store, chances are it was sorted and packaged by a robot. In packing plants in Eastern Washington, apples pass under complicated scanning equipment that sort the fruit based on size, color and condition.

Whooshh’s salmon technology can do the same. But with live fish.

The fish first swim into a large enclosed box. While inside, they briefly pass through a pocket of air. While in that air pocket, photos are taken. A computer then determines what type of fish it is, whether it has any visible wounds and how big it is.

“The computer is making a decision before it gets to the tube,” Bryan said.

If, for instance, a predatory and invasive Northern Pike swims into the machine, it could be diverted to a “grinder,” Bryan said. Or, if a hatchery-raised salmon appeared, it could be diverted back downstream. Those decisions would be up to the fishery managers, Bryan said.

He believes this could reduce the predator population in reservoirs, giving salmon some respite.

As for heat stress, preliminary studies have shown that fish using the salmon cannon are able to travel faster and farther upstream before the summer heat makes portions of the Columbia impassable.

And Bryan said he has some ideas on how to help smolts trying to return to the ocean, although he isn’t ready to talk about them.

“Our whole goal has been fish passage,” he said.

The tribes

Last week, before the Salmon Cannon went viral, the Colville Confederated Tribes released 30 salmon into the Columbia River above Chief Joseph Dam. That’s the first time salmon have been in that stretch of river since the dam was built.

Now, a Whooshh Salmon Cannon is on a barge at Brewster, Washington, waiting for final approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to travel upstream to Chief Joseph to conduct live-river tests. There is already one installed at the Cle Elum hatchery, transporting fish from the hatchery to Cle Elum Lake.

If approved by the Corps of Engineers, the system could become an important tool in the Colville Tribes’ effort to restore salmon to their native waters in the Upper Columbia.

The Whooshh system costs between $2 and $4 million, depending on where its installed.

“This could serve as another viable way that we can move fish,” said John Sirois, a fisheries coordinator for the Upper Columbia United Tribes. “We’re all about having another avenue to help the fish and help the salmon.”

There are plenty of legal and biological questions to be addressed before Salmon Cannons become a regular sight at Columbia River dams. But the innovation has momentum. And Bryan, the founder and CEO, is passionate.

A logical and linear thinker, he spends most of a two-hour interview talking about the science and physics behind his work. But, toward the end, another deeper motivation appears to surface.

As a baby, Bryan was very sick, was even on death’s door, he’s told. And so, his aunt, a nun, had her entire convent pray for her baby nephew. He survived.

“I’m still here for some reason,” he said. “Maybe it’s for the fish.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the city in which Whooshh Innovations is based. It’s based in Seattle.