Woodstock at 50: Local festival attendees remember peace, love and mud on anniversary

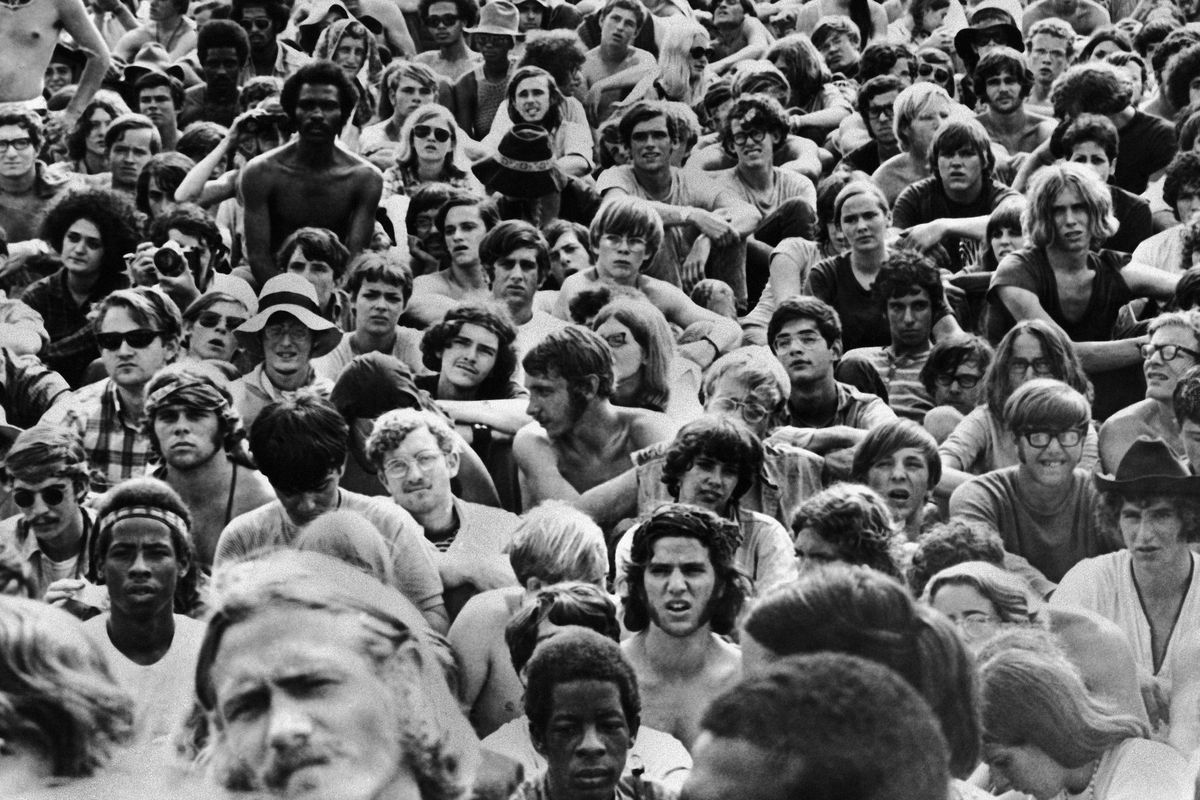

They came by the car- and van-load to the small dairy farm in upstate New York 50 years ago this week, thousands of them in search of either good music, a good time or a little of both.

The national media at the time knew little of what to make of the “long-haired, blue-jeaned and bell-bottomed” throng that jammed the highways leading to the town of Bethel, about 100 miles north of New York City, in the words of one account published in the Aug. 16, 1969, edition of The Spokesman-Review. The early stories of Woodstock focused mainly on the human suffering of the event, with reporters asking about deaths, dirt and drugs.

“This isn’t a music festival,” one security guard is quoted as saying in a story a day later. “It’s a drug convention.”

The drugs were there, say locals who attended the three-day festival whose 50th anniversary is being celebrated later this week without the massive, follow-up concert that original organizers had envisioned. But what also blossomed in that alfalfa field 50 years ago has taken on an almost mythological significance as a distinct moment in history that belonged to the young.

‘They just underestimated everything’

Bill Burke’s mother promised his father, half a world away fighting in Vietnam, that the family would not be attending the peace and love festival in upstate New York.

“Once a month, the husband or the spouse that was in Vietnam got a chance to call home,” said Burke, known in Spokane for pioneering the Pig Out in the Park festival of grub and grooves. “On the day we’re getting ready to go up to Woodstock, I get a call from my dad.”

“My dad goes, ‘Oh no, you can’t go,’ ” remembered Burke, 18 at the time. “ ‘We’ve heard about that. You can’t go.’ ”

But the family, then living in New Jersey, piled in its 1968 Pontiac Firebird anyway and started making the drive to Bethel. Like many, according to accounts that ran in The Spokesman-Review and newspapers nationwide, the Burkes got caught in a traffic jam 25 miles from Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm.

Burke’s mom and younger sister turned around, intimidated by the massive crowd that would swell to an estimated 500,000 concertgoers by the end of Aug. 17, 1969. But the brothers bummed rides into town, leaving in the Pontiac a quartet of three-day, $18 tickets ($125 in 2019 dollars) Burke had purchased through his job at Philadelphia’s Electric Factory music venue.

“That’s why I still have them,” said Burke, whose stepmother later found the tickets in pristine condition (they now reside in a safe-deposit box the festival promoter owns). “Because my mother took them home.”

The crowds had already overwhelmed ticket-takers, so the brothers had no trouble sauntering up to the stage for the early Sunday morning performance by Jefferson Airplane, which followed a 5 a.m. set by the Who (lead singer Roger Daltrey would later write in his memoir about the anxiety of waiting to play for half a million people and calling it “chaos”). A frizzy-haired, white-clad Grace Slick took the stage, promising “morning maniac music.”

Despite the legendary psychedelic performance on display and a break in the soggy weather, Burke remembers only the crush of the people and the muck.

“It was miserable,” he said. “If my conscience, or my memory, serves me right, it was terrible. It was horribly dirty. It was very crowded. You couldn’t find a clean place to go to the bathroom to save your life.”

The main mistake of the organizers, Burke would learn later in establishing the Labor Day feasting fest in Riverfront Park, was their inability to anticipate how big the crowd would be.

“They just underestimated everything, and it’s an interesting problem to have,” Burke said. “It’s not the best problem to have. It’s better than overestimating, but they underestimated everything. I think they underestimated the will of the generation to get out and be seen.”

The brothers hitched back to their home in New Jersey, outside Philadelphia. It wasn’t until later, he said, that the family let their dad, a U.S. Air Force colonel, know they’d defied his orders and gone to Woodstock.

“We didn’t talk about it. It didn’t come up until, maybe, five years after he came back from Vietnam,” Burke said, chuckling. “There was really no need to talk about it.”

‘Then the rains came, and someone slipped me some acid’

Bob Damato had just graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when he and a few buddies decided to make the drive to Bethel.

“There were four of us,” Damato, who now lives in Nine Mile Falls, said. “And we did not know what we were getting for, nor did anyone else, really.”

The friends drove a 1957 Plymouth “with fins on it” to the concert they’d seen promoted on flyers in Harvard Square, Damato said. They’d planned to buy tickets when they arrived, but found out – like Burke – they weren’t necessary.

“Then the rains came, and someone slipped me some acid,” said Damato, who was 22 in August 1969. “I lost one of my sneakers in the mud. And basically didn’t have a good time, and we didn’t realize we were making history.”

So sure was Damato that what was being pitched as a three-day “Aquarian Exposition” in White Lake, New York, wouldn’t be memorable that he didn’t bring the camera he used to document what he called the “hippie movement” in and around Boston.

“Back in the ’60s, I was the kid that always had a camera around my neck, everywhere,” he said. “I had a little Leica, with a wide-angle lens.

“I did not bring it to Woodstock. And I’m kind of glad I didn’t, because it wouldn’t have made it home.”

Damato said he remembered some of the acts, but his group was toward the back of the crowd that was hundreds of thousands of people strong. Among the performances he remembers are Joe Cocker with the Grease Band, who took the stage Sunday afternoon a few hours after Jefferson Airplane. Cocker arrived at the venue via helicopter because of the traffic and performed as his final song a version of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends,” which is included in the 1970 documentary about the festival.

Like Burke, Damato said he was glad to be in Bethel for the concert and a part of history. After coasting back to Boston on fumes following the concert, he never saw two of his buddies from the road trip again. And knowing what he knows now, he might not have made the drive.

“Some people had a good time,” Damato said. “I was one of the guys who didn’t.”

‘But I tell you, it made for great hallucinations’

Eilee Weiser kept most of her mementos from her five-day sojourn upstate in August 1969.

Original Woodstock brochures that featured a map first to Wallkill, then White Lake after local authorities at the prior site shot down the location due to portable toilet issues. Prints developed from her Instamatic camera, glued to pages of a photo album, show friends frolicking in the mud and camping at their site near the main stage. Dried daisies are pressed into the book, which Weiser said were dropped from a helicopter above the crowd after a rainstorm.

“It was more than just music,” said Weiser, who was about to enter her final semester and graduate early from high school in the Rockaway area of Queens when she went to Woodstock. “It was all these people. It was a community of people, and meeting people with a like mind. And knowing that there’s others like us, out there.”

Weiser saved up wages from her dollar-an-hour job at a New York City five-and-dime store to attend the festival, which she found out about in the pages of the Village Voice newspaper. She traveled to Bethel a couple of days early to stake out a good campsite, with only the promise of a friend who’d attended a couple of Cub Scout meetings that he knew how to pitch a tent.

But her friends weren’t the only ones who had that idea.

“We bypassed the turnoff to the festival, because we saw all these cars,” Weiser said. “We said, ‘Oh, there must be a farm thing going on, it could not possibly be people going to the festival because we’re early.’ ”

Thousands of people had already lined up to stake their claim near Fillipinni Pond, an area behind the stage that was protected by trees and later became a destination spot for skinny-dipping. The group found a good spot to raise a moldy, canvas tent that they’d dug up from someone’s garage. It smelled terrible, Weiser said.

“But I tell you, it made for great hallucinations,” she added, laughing.

For breakfast, she ate from big pots of brown rice and granola that were being distributed by members of the Hog Farm, a commune in New Mexico brought in by the festival’s sponsors. It was the first time Weiser, who’d grown up in Georgia and western Pennsylvania before moving to New York City, had eaten that type of food.

“It was fabulous, this stuff tasted so good,” Weiser said. “It was like, this is real food. I’d never had that type of rice before. All I ever had was this instant stuff, in a box.”

Their sole source of information about the outside world those three days came from the stage, Weiser said. Arlo Guthrie, the famed folk singer and son of Woody Guthrie, appeared just before midnight Saturday and read from the New York Times that an estimated 300,000 were camping out “in a sea of mud,” before launching into “Coming Into Los Angeles,” a song inspired by his own discovery of drugs in his briefcase on a flight home from London.

Weiser stayed all the way through Jimi Hendrix’s final performance Monday morning, featuring a hair-raising rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” before his “Hey Joe” closed the festival. Her home on Spokane’s South Hill has become a shrine to the spirit she said the festival embodied. Peace sign sculptures are affixed to the front of her garage and hang in her backyard garden; another peace sign has been cut into the grass in her front yard, a symbol she seeded ahead of the 40th anniversary of Woodstock that has remained in the decade since after neighbors requested she keep it.

“Can you imagine that many people together, and no fights?” Weiser said. “No anger?”

Legends made of mundane things

Out of the mud rose cultural significance.

That’s the point of Spokesman-Review staff writer Christopher Bogan, who on Aug. 17, 1979, penned a 10-year retrospective of Woodstock with the subtitle, “It was not the beginning of an era, but a euphoric end.”

“Legends are not usually made of such mundane things as mud,” Bogan wrote. “But then Woodstock remains very real for me.”

Separating the real Woodstock from the mythological has been difficult for subsequent generations, said Steve Beda, an assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon in Eugene. Beda’s research focuses on American social movements in the 20th century, including much of the activism that took place both before Woodstock and after.

“If you look at the news accounts in 1969, people were actually kind of miserable at the show,” Beda said. “Then, remembering it later, people sort of discount the misery, which is not uncommon in any historical account.”

Beda uses the music of Woodstock to teach students about what he says is a transition in political activism in the 1960s to the post-Vietnam and Watergate era. There’s a shift from the optimism of the early years to a pessimism that’s a reaction to things such as the deadly Tet Offensive, the divisive Democratic National Convention in 1968 and President Richard Nixon’s election to office, he said.

“It’s seen as a bookend of the optimism of the 1960s and a new era of social movement activism,” Beda said.

Consider two “protest” songs that feature in the Woodstock documentary. In the first, Country Joe and the Fish implore the crowd to sing along to “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixing-to-Die Rag,” a rallying cry against the war in Vietnam that’s sung with a traditional folksy melody. Compare that to Hendrix’s performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” a solitary, almost violent rebuke of the traditional anthem that is played without audience participation and includes guitar distortions mimicking gunfire and bombs.

“It’s not unorthodox. I thought it was beautiful,” Hendrix told Dick Cavett on his nighttime talk show a month later, referring to his rendition of the song.

Both of the protest perspectives were on display at Woodstock, Beda argues, casting some doubt on the idea that the festival was the simple expression of peace and love that it’s come to be understood as by people trying to make sense of its historical significance.

“People forget some of that violence, and that hardship, that was at Woodstock,” Beda said.

What about a new Woodstock?

Despite that complicated history, there’s been no shortage of efforts to recapture the spirit of Woodstock in a new festival. But those who were there doubt such a cultural moment could occur again, in a society that may be just as politically fractured as the United States in the late 1960s but unable to rally around a particular ethos or genre of music, nor organize properly to create an experience that modern festivalgoers would expect.

“Should it happen? Wouldn’t it be great if we lived in a world where it could happen?” Burke asked. He said he believed the reason a 50th anniversary concert ran into such speed bumps is the fear of too many people showing up and overwhelming sanitation and safety measures.

That was the case in 1999, when promoters brought a wide variety of musical performers to Rome, New York, about 100 miles from the Yasgur farm. After several days of reported lack of water and sanitation, concertgoers set large fires and looted ATM machines during the final performances of the weekend.

Damato said he didn’t believe all the stars could align once more to make another Woodstock.

“It’s not going to happen again,” he said. “This was just a string of coincidences, and things that fell into place,” he said. “It was something that could only happen in that era.”

It hasn’t stopped at least one of the original organizers from trying. Michael Lang, a co-creator of the original festival and involved in planning for subsequent anniversary celebrations in 1994 and the 1999 ill-fated event, announced early in 2019 plans to hold a Woodstock 50. Those who’ve seen the seminal documentary will recognize Lang as the curly haired, motorcycle-riding organizer seen with a Cheshire cat grin as he’s asked about the potential financial losses of the event.

After several venue changes and delays in ticket sales for Woodstock 50, organizers released all of the musical acts from their contracts at the end of July. Performers originally scheduled to appear included veterans of the 1969 event, including John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival, Santana, Dead and Company (known then as the Grateful Dead) and Canned Heat. The slate had also included modern superstars of multiple genres, including Jay-Z, the Black Keys and Halsey.

On July 31, Lang announced the anniversary show was officially canceled. There will be no repeat of the dawning of the Age of Aquarius in 2019.

That makes sense, Weiser said. Woodstock is an artifact of a political spirit and like-mindedness that doesn’t exist anymore, she said.

“You can’t replicate what happened,” Weiser said. “And I wasn’t going to go. I have my memories of being there. Why try to create something as a memory? My memory is as sharp as when I was there, because I was so impressed with all these beautiful people and the kindness.”