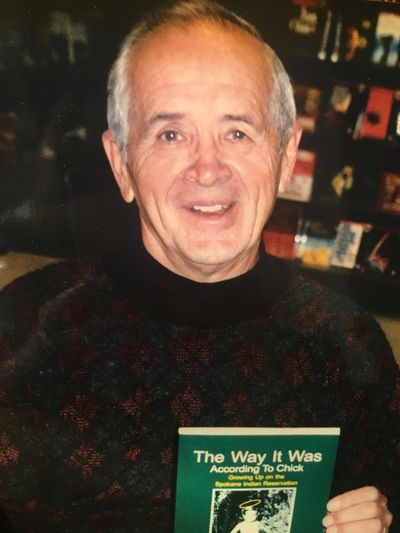

Friends, relatives remember Bob Wynecoop, author of tales about growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation

Bob “Chick” Wynecoop was a good Christian, but he never liked praying publicly, so much so that as a child he found a loophole. At summer Bible school, classmates were taking turns leading the class in prayer. When Chick’s turn came around, he asked everyone to join him in silent prayer. Once he figured enough time had passed, he said, “Amen.”

This was one of his wife’s favorite Chick tales, although Lois acknowledged there are many to choose from.

His book, “The Way It Was According To Chick,” is a collection of stories of his childhood on the Spokane Indian Reservation, told with mischievous humor reminiscent of a Mark Twain tall tale.

Chick Wynecoop, a member of the Spokane Tribe, died in Minnesota on Nov. 24, at the age of 83 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. On July 27, his ashes were buried in a Smokey Bear cookie jar at the Presbyterian Cemetery in Wellpinit, an appropriate selection given his long career working for the U.S. Forest Service. The plot overlooks a log cabin on his family’s ranch.

The cabin was where he began his life – and his book, which begins, in David Copperfield fashion, with his birth.

“The local Indian Health doctor who assisted with the delivery was slightly inebriated when he arrived at the folks’ small log home on the Spokane Indian Reservation in the foothills of eastern Washington State,” Chick wrote. “Accounts of his less-than-sober state must have been true because he failed to register my birth, which caused me a few problems later in life.”

Chick’s plan wasn’t to publish a book. He wanted his daughter, Kerry Coolis, and son, Keith Wynecoop, to have a record of his childhood. So, in what Tina Wynecoop, his sister-in-law, described in the introduction as the “winter” of Chick’s life – after his retirement from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Minnesota – Chick decided it was time to put pen to paper.

As with the pattern of the stories of his childhood, one thing led to another. Tina suggested he show his stories to Suzanne Bamonte, owner of Tornado Creek Publications and wife of the late Tony Bamonte, the Pend Oreille County sheriff known for exposing corrupt law enforcement. Suzanne said she and Tony became interested in Chick’s stories because of his natural talent as a storyteller.

“I just remember editing and proofreading the book, I would just end up laughing out loud at some of his stories,” Suzanne Bamonte said. “It was always this joke of who in the family would tell the story first.”

Chick’s book was published in 2003. He wasn’t the only person in his family to write. His brother David Wynecoop’s book, “Children of the Sun: A History of the Spokane Indians,” was published in 1969, and his brother Arnold “Judge” Wynecoop published “The Shooting Star: Growing Up on the Spokane Indian Reservation” in 2010.

“They were just the history of what I did through my life,” Judge said. “You wonder what your parents did, so that’s what I was doing.”

The Wynecoop family has long been prominent on the Spokane Indian Reservation. In 1979, Clair Wynecoop, Chick’s father, posthumously received the first and eponymous Clair Wynecoop Memorial Award for promoting and preserving Native American history and heritage. The award was presented by the Pacific Northwest Indian Center Board of Trustees. Clair was long the director of Midnite Mines, a former uranium mine in the Selkirk Mountains. He received the award a decade following his death, and it was accepted by his widow, Phoebe Wynecoop.

Like his father, Chick was active in giving back as an adult, building houses for Habitat for Humanity and volunteering at Mary’s Place, a transitional home for the homeless in Minneapolis, Lois said.

During his childhood, Chick and his six brothers tried to be good, but trouble often found them regardless. Envious of their father’s ability to blow smoke rings and roll his own cigarette one-handed, they decided to try smoking, experimenting with oat straw in their barn.

“It was like trying to smoke a flame-thrower,” Chick wrote. “Since the straw was hollow, the burning smoke came right up the hollow core when you sucked on it.”

In a few cases, he and his older brothers were clearly at fault – for example, convincing their younger cousins to pee on the cattle’s electric fencing or stick their tongues to the frozen water pump, in the style of A Christmas Story.

“With the usual taunt, ‘Come on, it won’t hurt,’ we eventually got some sucker to bite,” Chick wrote.

Accounts of how he received his nickname differ: Clair claimed the name derived from a famous wrestler, Bob Robert Chick, but Chick and Judge contended his ribcage looked like a chicken’s. Either way, it stuck.

Lois said hearing Chick’s stories, she was amazed Chick and his brothers had survived childhood. Lois always called him Bob – it was how he’d introduced himself – except when they became separated in the grocery store because, chances were, there would only be one Chick.

Lois and Chick met in 1968 after Bob had broken up with a girl who worked at First National Bank in Helena and, a few days later, noticed Lois working there. He asked his ex-girlfriend if Lois – the girl in the purple dress – would be interested in dating him.

“I said, ‘Is he a nice guy?’” Lois said. “She said, ‘Yeah. he’s really nice guy. But it never would have worked for us, because I’m Catholic and Bob wanted to marry a Protestant, and I smoke and he doesn’t want to marry a smoker, and I want a whole bunch of kids and he only wants two.’ I was perfect for him, because I fit all of the requirements.”

After a five-month, long-distance courtship that began after Chick was transferred by the Forest Service to Orofino, Idaho, the two wed. Working for the Forest Service had been Chick’s dream since high school.

“He saw a promotional in-color picture early. It was kind of like a Disney production, where they showed the life of a forest person that showed beautiful streams, forests and animals, and that was his career,” Judge said. “He absolutely stuck with it, I could not believe it, but he did not vary.”

It would follow that Chick was an outdoorsman, and along with four of his Forest Service buddies from Orofino, he backpacked regularly. The group achieved a mythology of sorts for their 100-mile or so hike through Bob Marshall Wilderness in 1975, and their 2017 reunion was reported by the Missoulian newspaper. At this point, Chick’s struggle with Parkinson’s prevented him from making the trip.

One backpacking trip Chick took with the same group had always haunted him, Lois said. In 1995, Lois’s nephew, Jeremy Moors, went missing during a backpacking trip in Montana. The men searched for him relentlessly, but Moors was never found.

“They went up there looking for him, and it was quite a quest and very amazing that they all stayed so dedicated to it,” Lois said. “It was such a tragedy for all of them.”

The memory of Chick that Judge holds closest is huckleberry-picking, and Tina often tagged along.

“Lois would always call it ‘doing a Judge,’ because we’d be gone 18 hours,” Tina said. “We weren’t camping, but we were out in the mountains for a long day.”

Tina remembered being caught in a hail storm on the mountain with Chick and Judge. They couldn’t find shelter, and the hail was coming down hard, but Chick “had his wonderful old wore-out straw hat on, and he didn’t suffer at all.”

“Blue fingers are the marks of a good huckleberry picker, and blue lips and teeth always show a good huckleberry eater,” Chick wrote. “Once you eat them, you never forget their strong, very distinctive flavor. To me, they make the best jam.”