First black starting QB reflects on changes in game, society

Marlin Briscoe didn’t want to be pigeonholed simply because of stereotypes against black men. He was a star quarterback in college, and he believed he had the talent, intelligence and leadership skills to be one in the pros.

Fifty years ago, during an era of massive social upheaval in the United States, just getting a chance to prove it took a risky ultimatum.

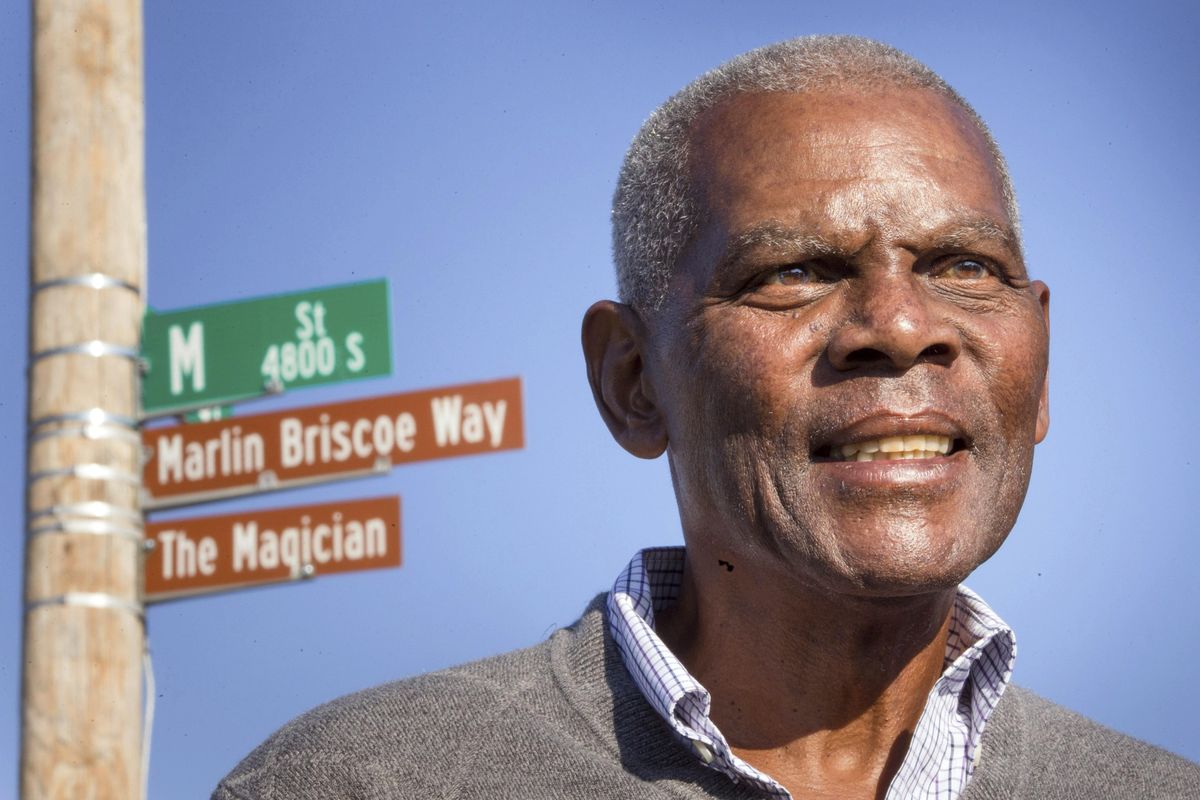

Briscoe refused to switch positions after being drafted as a cornerback by the Denver Broncos, telling his team that he’d return home to become a teacher if he couldn’t get a tryout at quarterback. Denver agreed to an audition, and that season the 5-foot-10 dynamo nicknamed “The Magician” became the first black quarterback to start a game in the American Football League.

“It’s just so many different historic things that happened in the year 1968, it was unfathomable,” Briscoe, now 73, told The Associated Press. “It just seemed poetic justice, so to speak, that the color barrier be broken that year at that position. For some reason, I was ordained to be the litmus test for that. I think I did a good job.”

Briscoe’s groundbreaking accomplishments were somewhat lost in the shuffle during one of the most transformative years in U.S. history. Civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated in 1968. Civil rights riots broke out across the country and there were numerous protests of the Vietnam War. And less than two weeks after Briscoe’s first start, U.S. track and field stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised black-gloved fists on the medal stand at the Olympics to protest America’s social injustices.

But Briscoe’s legacy resonates among his contemporaries 50 years later, hitting on race as well as the pressures athletes face in pro sports. The Pro Football Hall of Fame calls Briscoe the first African-American starting quarterback in modern pro football history. Carolina’s Cam Newton and Seattle’s Russell Wilson have both considered Briscoe’s past as they contend for championships. Doug Williams, the first black quarterback to win a Super Bowl, counts Briscoe as one of his most important inspirational figures.

“I know the little bit that I had to go through, so I can imagine what he had to go through,” said Williams, who won the 1988 Super Bowl with Washington. “People were a little more accepted when I came through than when he came through.”

Getting on the field

Though Briscoe starred at Omaha University and eventually landed in the College Football Hall of Fame, he was drafted By Denver as a cornerback in the 14th round. Briscoe started last among eight quarterbacks during his tryout.

Helped by injuries and erratic play, Briscoe eventually stepped in for the Broncos as a reserve on Sept. 29, 1968, and nearly led a comeback against the Boston Patriots. He earned the next start against the Cincinnati Bengals, making him the first black quarterback to start a game in the AFL.

Briscoe started five games that season and was runner-up for AFL rookie of the year, attracting strong crowds and energizing a franchise that had yet to establish a winning tradition.

Despite his breakout season – he passed for 1,589 yards and 14 touchdowns and ran for 308 yards and three scores – Denver didn’t give him a chance to compete for the quarterback job in 1969. He said he was never given a reason why, so he asked to be released.

“The more I’ve known him and been around him and talked to him, you’ve got to give him respect for what he did during that time and what happened to him after that time,” Williams said. “That’s the part that gets me. But that’s the time he was in.”

Paying it forward

As a senior at Grambling, James Harris kept up with Briscoe’s 1968 season by going to the library to look up his statistics.

As fate would have it, Buffalo drafted Harris as a quarterback in 1969, putting him on the same team as Briscoe. It was Harris who became the AFL’s first black quarterback to open the season as a starter, and he said his roommate Briscoe was a critical mentor.

“We used to talk a lot about the dos and don’ts and things that he had been through. He was telling me the things I needed to be prepared for,” Harris said. “I felt that Marlin was the only person on the team that understood what I was going through.”

That included death threats, Briscoe said. “We had the race card on our careers because we were the first,” he said.

Harris blossomed at QB. In 1974, he played for the Los Angeles Rams and became the first black quarterback to win an NFL playoff game. He also was Pro Bowl MVP that year.

Briscoe said more work needs to be done both in the league and society. He has noticed that Colin Kaepernick has not been given a contract since his decision to kneel during “The Star Spangled Banner” to protest racial and social inequality. He believes President Donald Trump, an outspoken critic of Kaepernick, also bears some responsibility for some fans making racial comments toward black players, like a Texas superintendent who resigned last week after criticizing Houston Texans QB Deshaun Watson by saying black QBs can’t be trusted.

After all these years, Briscoe still sees shades of his old struggles.

“I grew up in the `50s and the `60s, when all that stuff was rampant, but you knew where you stood,” Briscoe said. “Today, you thought that all those attitudes were non-existent or filtered away to some degree, but with the Trump-isms, his philosophy has brought out of the woodwork that old-time thought process. That’s scary. It really is. It’s a scary situation.”