For Washington State’s Patrick Nunn and San Jose State’s Leki Nunn, a long journey comes full-circle Saturday night

PULLMAN – At Trinta Park in San Mateo, California, Vika Sinipata would station herself in the middle of the two baseball diamonds, planting a lawn chair behind one home run fence but not too far from the other.

Some afternoons, both boys would go long – Patrick on one field and Leki on the other. Suffice it to say, the single mom of two had a baseball collection even Cooperstown might envy by the time her sons finally decided to give up the sport.

“I used to get home run balls that were given to me as I’m sitting in the middle,” Sinipata said, “because both boys would hit home runs in between the two parks.”

Sinipata’s been having flashbacks like this all week.

Her sons are separated by 13 months, so they often played for the same Little League or Pop Warner organizations, but in different age brackets. Occasionally, those brackets aligned just perfectly so they could be teammates. Once, while one was a high school senior and the other a junior, they co-anchored Junipero Serra’s run to the state football championship game.

But never have Patrick and Leki Nunn been adversaries. Their mother is still warming up to that concept – and she’d better do so quickly.

Why’s that? Because Patrick is a backup freshman nickel safety at Washington State and Leki is a rotational freshman slot receiver at San Jose State. And because the Cougars host the Spartans at 8 p.m. Saturday in a nonconference game at Martin Stadium.

Although Patrick didn’t play in WSU’s season opener at Wyoming last week and Leki’s field time was limited when the Spartans debuted against UC Davis, it’s not totally impractical to envision a scenario in which both are playing in Saturday’s game – especially if the heavily favored Cougars establish a big lead, and Patrick Nunn replaces starting nickel Hunter Dale in the second half.

“I’ve been thinking about that,” Leki said Wednesday in a phone interview. “What routes I’m going to hit him with or in general, blocking him. I’ve just been thinking about everything on the field as well, in between plays should I talk to him or should we just keep it competitive and not talk.

“We’ll find out.”

Sinipata isn’t ready for that scene to come to life. Patrick outgrew his older brother his freshman year at Serra and now has 5 inches and 25 pounds on Leki, according to their school bios. If Leki catches a pass over the middle, and Patrick begins to rev his engine, Sinipata may have to blindfold herself.

“As a mother it’s pretty nerve-wracking to have one on the defense and one on the offense,” she said. “I told (Pat) he’s younger so he needs to do what a younger brother does and respect an older brother and he said, ‘We’ll see about that mom.’ ”

Fortunately, Sinipata wins either way. And take it from her, a mom who single-handedly raised two college football players – and did so through considerable adversity – this success story was never a guarantee.

When football practice at Junipero Serra High was over, a handful of teammates went home to $10 million mansions scattered throughout the most affluent district of San Mateo – a Bay Area suburb just south of San Francisco. Patrick and Leki would be invited over, but they understood there was a stark difference between the life they were visiting and the one they’d return to when the hangouts were done.

For approximately two months during Patrick’s sophomore season, and Leki’s junior year, Serra’s star football players slept on motel floors.

Previously, they’d lived with their grandparents, Paul and Anna Sinipata, who’d taken in both brothers when their mother was sentenced to a two-year prison sentence – something Vika doesn’t want to detail, or dwell on, “because I’m still building up my life now.”

But she does concede those 25 months were agonizing beyond measure. She missed Leki’s freshman football season, Patrick’s first year of high school (he didn’t play freshman football after breaking his leg during a pickup basketball game) and all of the life events in between.

“I cried every day, I didn’t want to eat,” she said. “I think the second or third month, I saw I lost 30-40 pounds. I just would not eat because I was so depressed. And I was one of those moms where I was there for breakfast, I was there for practice, I was there for games. You’d never, ever not see me at my kid’s events. Never. Everything in my life was always about my kids and the boys played year-round sports, so I never took a break.”

Vika didn’t let her sons visit, but she received updates through various friends and family members. That gave her hope. Leki, she’d heard, was becoming an explosive quarterback/running back for the Padres football team – “they said that kid would not slow down” – and she took solace in knowing each day that passed was one less she’d have to spend without her sons.

“It was my kids that kept me going, kept me going every day,” Sinipata said. “That was my motivation, to be able to come back home.”

Sinipata and her ex-husband split up when the boys were young and Patrick Nunn Sr. is in custody and serving a life prison sentence, she said. He’s in communication with both and still follows their football careers, but it’s been years since Patrick and Leki have seen their father.

So, for two years, the brothers resided with their grandparents, who’d have to make some desperate financial sacrifices to afford the steep tuition at Serra, which runs higher than $21,000. Paul and Anna Sinipata pawned precious family heirlooms from their native island of Tonga just to keep the brothers together at Serra, because they thought it provided an academic and athletic safe haven for Patrick and Leki.

“They’re really our world,” Leki said of his grandparents, “and I owe it a lot to them and basically each game is a personal vendetta for me just to make them proud and see how far we’ve come and how much they’ve put into us and the good things are coming out of it.”

Shortly after Vika was released from prison, she decided it was in her family’s best interest to move elsewhere. So Vika, Patrick and Leki left in the middle of the night and checked in to a nearby motel.

They eventually moved into a second motel and then a third before finding some stability and settling into an apartment, almost two months after leaving their grandparents’ home.

“The whole process was difficult,” Leki said. “… Football was sort of that getaway from all of that.”

The core value taught at Junipero Serra High takes on more a literal meaning for Patrick and Leki Nunn.

“Brotherhood.”

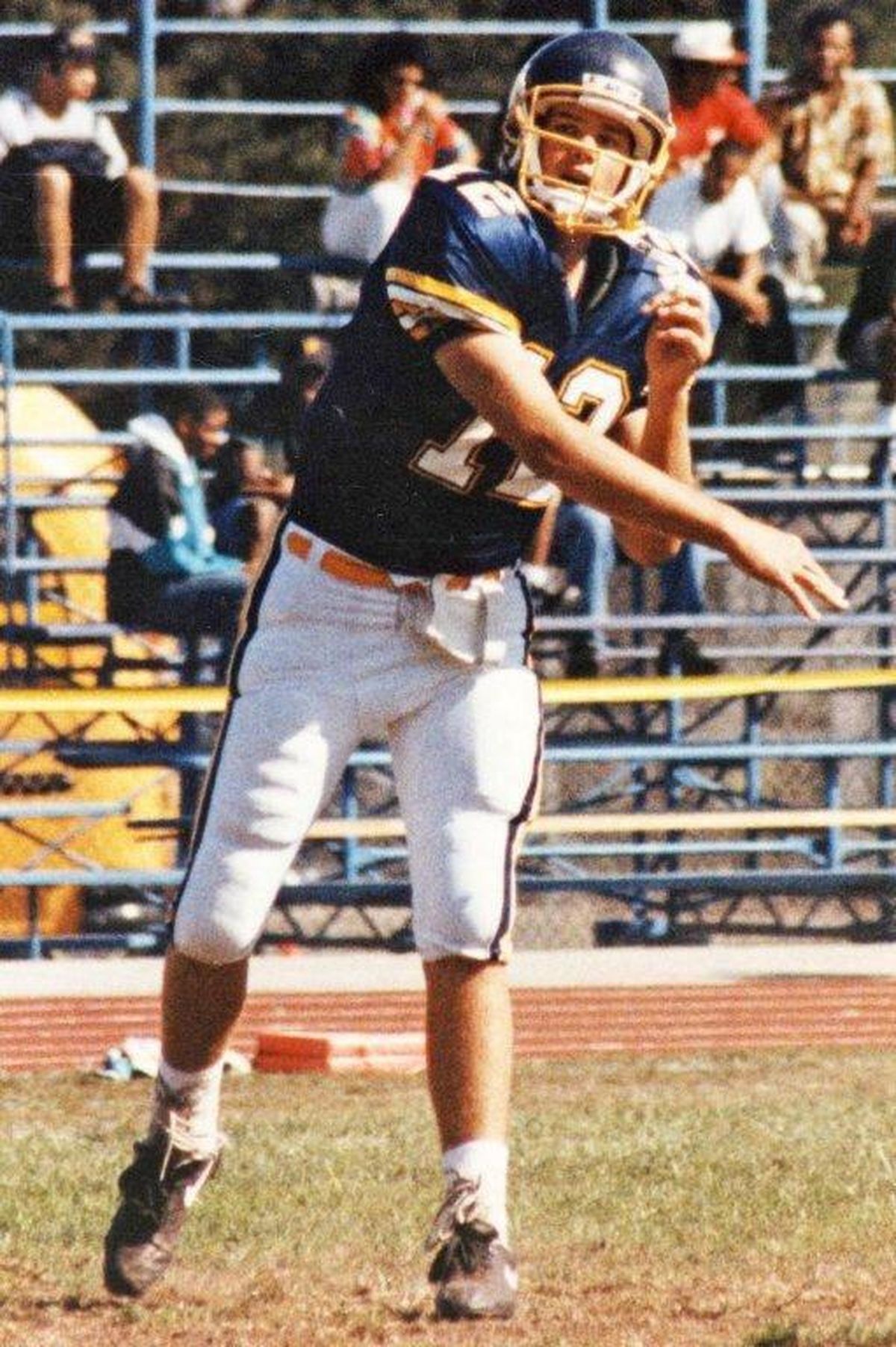

There’s often an intrinsic connection between siblings in the athletic arena. Here’s a glimpse of what that looked like for the Nunn brothers during the 2016 football season. Leki, a senior quarterback, accumulated 3,027 yards of offense – 1,972 passing and 1,055 rushing – and accounted for 27 touchdowns. Patrick, a junior receiver and his brother’s safety blanket more times than not, caught 26 passes from Leki for 415 yards and six touchdowns.

“Obviously, you see how tall he is, he has length to him so usually when I get in trouble the first thing I’m looking for is his hand up and then if his hand’s up, the ball’s going up, too,” Leki said. “That was the mentality, just all about trust.”

And their mother assures, “The times when Pat didn’t get to the ball I would hear about it at home. They would go at it.”

Patrick Walsh typically knows about the talented eighth-graders that are a year away from joining his Serra football program, but the Nunn brothers arrived on his porch as a surprise package because they’d transferred from St. Timothy’s – another San Mateo-based Catholic school that doesn’t often feed students to Serra.

Years later, they’d become two of the most exemplary athletes in Serra history – not insignificant at a school that claims Tom Brady, Barry Bonds and Lynn Swann.

Walsh likes to call Leki “Steph Curry on cleats” because of his improvisation skills and ability to turn bad play calls and frantic breakdowns into breathtaking touchdowns.

“It’s just, ‘Wow,’ ” Walsh said, labeling Leki “one of the most electric quarterbacks we’ve ever had here – even this league has ever seen.”

For example, Leki’s 4,266 career passing yards are the most in school history. Brady, by many accounts the best QB to have ever played in the NFL, sits three spots lower with 3,514.

Both brothers projected as potential college baseball players, but Leki hung up his glove his freshman year when, well, he couldn’t find it. It’s no exaggeration. He misplaced his mitt before a 2013 baseball practice and rather than continue his search, or borrow a teammate’s glove, he quit on the spot.

“The best thing to ever happen to Serra High School football was freshman year, when Leki Nunn lost his glove,” Walsh told The Mercury-News.

Patrick Nunn, because of his freshman year blacktop basketball mishap, didn’t arrive on the football scene quite as quickly, and being Leki’s not quite as athletically-inclined little brother, he spent a few years in his sibling’s shadow.

One game changed that.

With Leki graduated, Patrick broke out for 61 catches, 843 yards and nine touchdowns his senior year, also rushing for two touchdowns and throwing for two. After losing in the CIF state title game a year earlier, the Patrick Nunn-led Padres returned in 2017.

Nunn hadn’t played a lick of cornerback in his life, but Walsh felt he was Serra’s best option to cover 6-8 Cajon High receiver Darren Jones, a Utah commit who’d gone by the nickname “Baby (Randy) Moss” and had caught 92 passes for nearly 2,000 yards and 27 touchdowns before the title game.

“He locked him down, it was unbelievable,” Walsh recalled. “There’s probably only one human being in the history of our school that could’ve had that sort of success against that sort of player in that type of game. So it was great to see Patrick come full circle.”

Walsh, in his first season since 2012 without one of the brothers, urges both to “go to college, get married and start over again so we can get some more Nunns over here.”

At one point, SJSU coach Brent Brennan thought he might be able to attack the Cougars with two Nunns this Saturday, admitting, “I was hoping that we’d end up with Patrick here, trying to get the 2-for-1 with the brothers.”

But Patrick, who listed offers from a handful of Mountain West schools and Cal, pledged to WSU two days after the first game of his senior season at Serra. His work ethic and unflinching attitude earned him a place on WSU’s traveling squad this season, but the Cougars still see Patrick, like many of their freshmen, as a moldable piece of clay who’s nowhere close to his ceiling.

“He’s a real rangy guy, showed out in camp some and is doing some good stuff early for us and we’ll get him more consistent,” WSU coach Mike Leach said. “And he’ll get bigger, he’s going to be a big kid – bigger than he is now.”

WSU linebacker Jahad Woods, who’s bunking with Nunn on the road this season, characterizes his younger teammate as “a quiet guy, but aggressive when he plays.”

The Spartans have been enthralled with Leki, too.

“Leki’s a kid that takes football very serious … and I think that sometimes that’s a little bit rare in today’s age,” Brennan said. “I think some kids like getting recruited but they don’t really like playing football or working at it. Leki Nunn is the opposite of that, he likes working at football, he wants to be a great player.”

Sinipata, who works in HR consulting, moved out of the apartment she and her sons had lived in and relocated to San Jose. She’s now nine minutes from the SJSU campus and Leki, and only a few minutes from San Jose International Airport, the travel hub that can get her to Patrick. This was by design, of course.

WSU often doesn’t allow freshmen defensive players to speak to the media, and Patrick wasn’t made available this week, but Leki said he only expects a quick pregame encounter with his brother before the Cougars and Spartans kick off.

“We’ll just probably meet at the 50,” he said, “chop it up and go about our ways.”

Afterward, the brothers will exchange gloves and snap photos with their mother. They may also look her way for inspiration and strength at various points of Saturday’s game.

She might be a reminder of their trying past, but even more, she’s a symbol of their boundless future.

“There are moments where I’m just dead tired on that field, where like it’s just in the back of my mind and it drives me,” Leki said. “I didn’t really find (our past) difficult, I knew I had to take care of my bro and he had to take care of me, vice versa. … And we pretty much both did that, going to D-I schools and that was our main promise. We told our mom she wouldn’t have to worry, that we’ll get scholarships and we’ll go off and play ball in college.”