Capital punishment in Spokane: A history

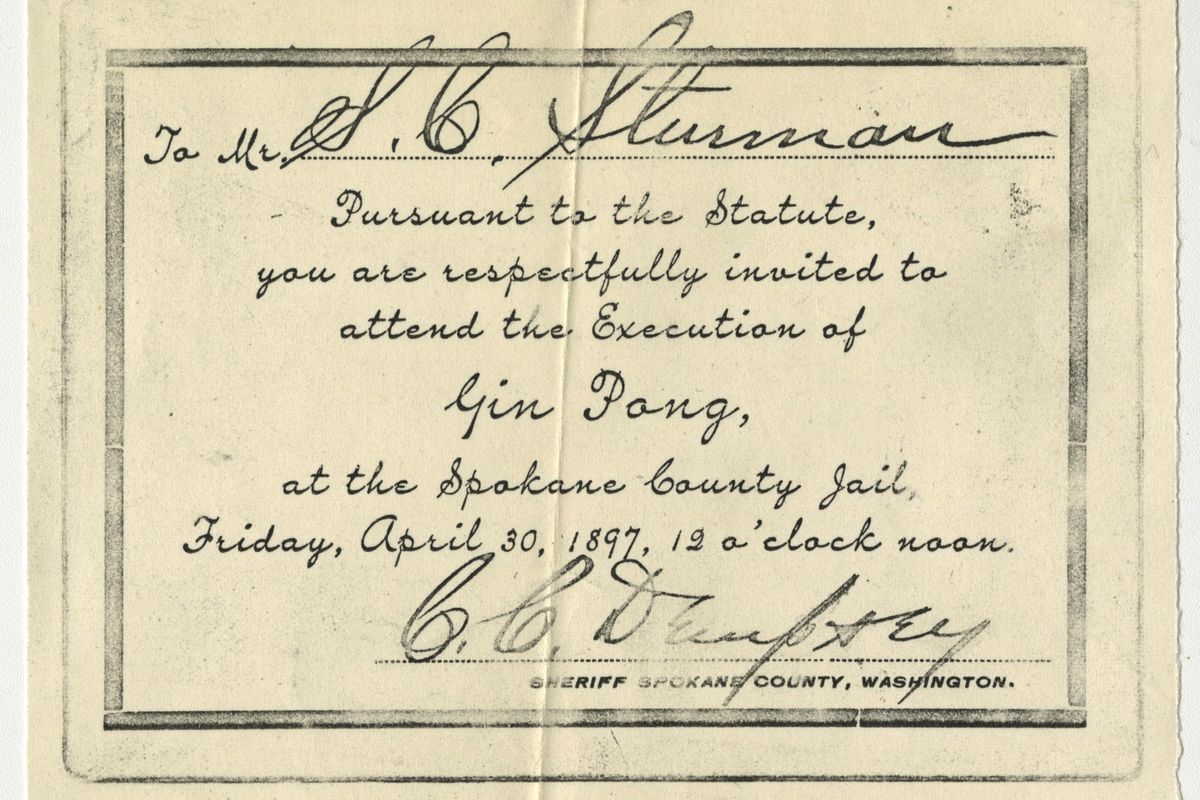

An invitation to an 1897 execution at the Spokane County Jail. (Spokesman-Review photo archives)

George Webster shot and killed Lise Aspland just west of Cheney, so he was hanged in Spokane.

In 1900, three years after the murder, the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported on Webster’s execution, the county’s “first legal hanging of a white man.”

The description of Webster as the first “white man” to be executed in Spokane is telling. Before him other men had been killed by the state, but they weren’t white.

Charles Brooks, an African-American, was convicted of murdering his white wife, and hanged in the Spokane County courtyard in 1892, the first legal execution in the county.

In 1897, invitations were sent out for the April 30 execution of Gin Pong at the Spokane County Jail. Individual names were handwritten on the invitations, noting that “you are respectfully invited to the attend the Execution.” Each was signed by the sheriff, Christopher C. Dempsey.

The Spokesman-Review described Pong as “a large Chinaman whom other Chinamen all despise and fear.” Some 4,000 people peered into Pong’s cell the day of his execution, including curious children and women “of refined appearance.”

There were many others. As the local history website Spokane Historical explains, there were “several other extracurricular executions in Spokane. Namely, those of Chief Qualchan of the Yakamas and 5-20 others who were hanged by Colonel George Wright in his campaign against the Indians in retribution for the battle at Steptoe Butte in 1858.”

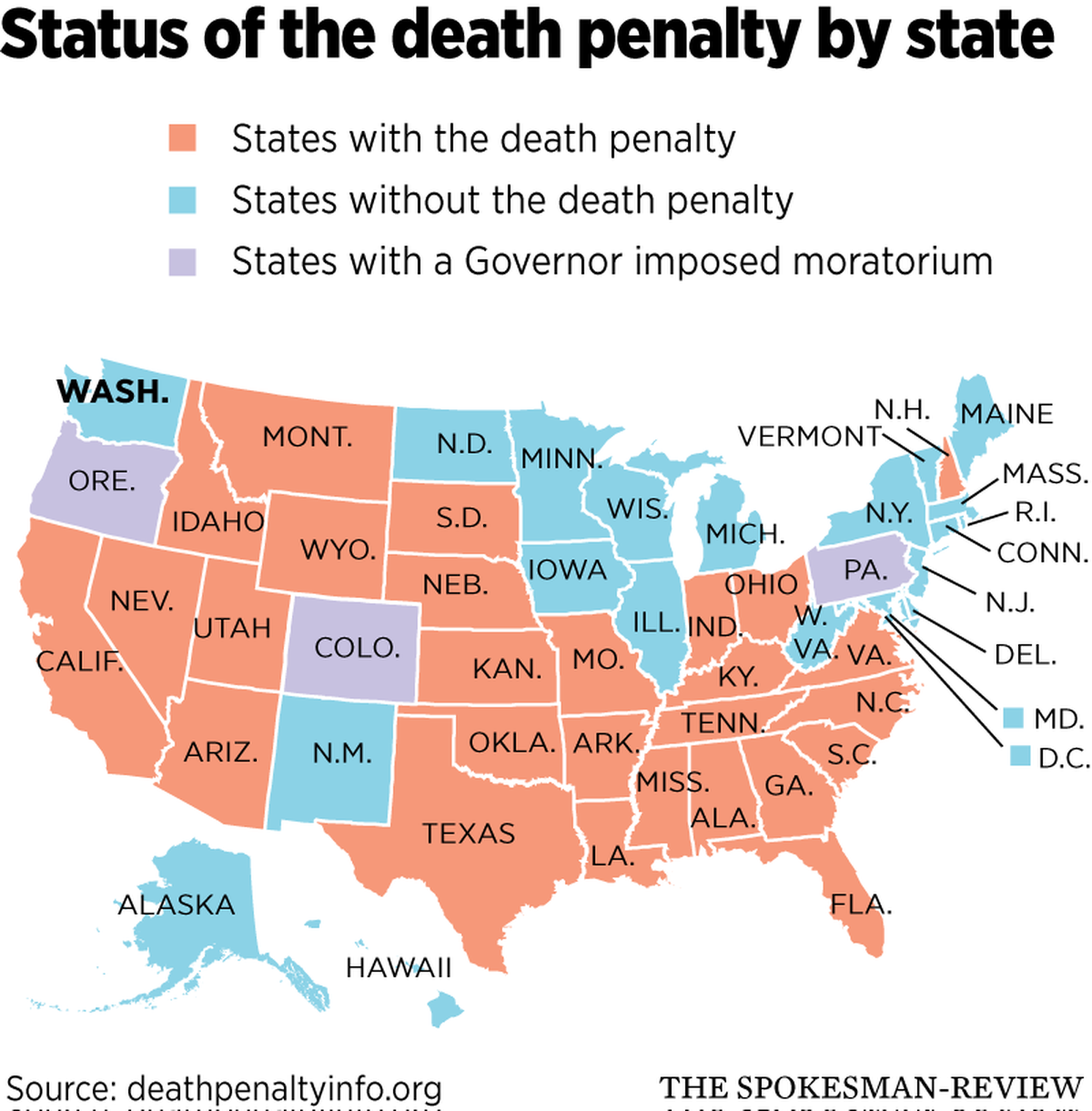

Recognizing the troubling role race plays in the nation’s criminal justice system, Washington state’s highest court struck down the death penalty on Thursday, saying it was applied arbitrarily and in a racially biased manner. If newspaper archives are any indication, race has long played a role in the most severe sentence the justice system can impose. Articles are rife with racially-charged descriptions.

The state Department of Corrections lists 78 people, all men, who have been executed since the Legislature amended the state Constitution and required all executions to take place at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Webster, Brooks and Pong are not on the list. Ten Spokane men are, including the first Spokane man to be executed: Henry Arao, who the paper called “the little Jap,” who was hanged for murder in 1905.

The paper’s slurs aside, Arao was almost surely guilty and later confessed to the crime.

“I drink some whisky and feel very much mad,” he said.

The story of Arao’s murder of his former employer, Sam Chow, offers a glimpse into the booming frontier town of Spokane, which at the time had a large Asian population.

Chow was a tailor with his own shop at 325 W. Main Ave., currently the site of a parking lot across the street from the Davenport Grand Hotel. He hired Arao, but Arao felt he was being cheated and quit to open his own shop at 204 N. Post St., the site of today’s River Park Square. Arao’s business didn’t do well, and soon he found himself in debt to his former employer.

According to his confession, Arao was up early on Dec. 29, 1904. He went to a saloon, drank whiskey and ate breakfast. He wandered to the Northern Pacific Railway depot, where Amtrak and Greyhound vehicles operate today, and made his way toward Chow’s shop and home.

At 7 a.m., Arao knocked on Chow’s door. Lucy, Chow’s wife, let him in and went to start a fire in the home’s potbelly stove. She soon heard a commotion and yelling. Arao burst from the house with a bloody knife, she said, and jumped the fence. Upstairs, she found her husband, stabbed and bleeding. He was dead by the time the authorities arrived.

On the lam, Arao walked 19 miles to Freeman, hopped a train to Fairfield and rode a wagon to Waverly, a town with a significant Japanese population where he sheltered in a shack for 12 days. Out of food and feeling time and distance had made him safe, he went into town to get food. But a well-circulated $300 reward had been placed on his head, and he was recognized and captured.

Known as a “troublemaker” in Spokane’s Asian community, Arao’s guilt was probably never in question, and it didn’t take long for a jury to sentence him to death. At 3:30 a.m. on June 30, 1905, Arao was woken and led to the gallows erected in Walla Walla just the year before. He was dead an hour later, the third person to be executed by the state and still the only person of Japanese descent.

The next official execution listed in the state’s records is that of Joseph Gauviette, a 44-year-old plumber, but The Spokesman-Review archives show others narrowly avoided the same fate. James Dalton was arrested for murder in May 1905 and was to be hanged two years later at Walla Walla, but a Senate Journal reports that his sentence was commuted to life in prison.

Charles Fillpot was arrested for murder in June 1908 and he too was to hang in Walla Walla. But again, a Senate Journal from 1911 said his sentence was commuted to imprisonment after 749 citizens of Spokane, Stevens and Douglas counties, as well as several “leading and reputable citizens of the state of Missouri,” wrote letters in his support.

Regardless, the hangings went on. In 1910, a Spokane teamster named Frank Barker, 23, was executed. Fourteen years passed before the next Spokanite was hanged. In December 1924, Tom Walton was executed for murdering “S.P. Burt and George MacDonald.”

On Sept. 12, 1930, the Associated Press reported on the hanging of Archie Moock, a 33-year-old millworker who had been convicted of killing Catherine Clark, from Boston. Clark came to town “in response to letters promising marriage” signed by an unknown man named Murphy. Instead of marriage, Clark “was killed in the woods near Spokane with a hatchet.”

Moock, who is referred to as “Much” by the state, denied his guilt through his last hours, when he “read without emotion letters from the eldest of his five children bidding him farewell” in his cell.

In December 1931, a Spokane mechanic named George Miller, 48, was executed. Seven years later, a 21-year-old “laborer” named Stanley Knapp was hanged for a downtown Spokane bank robbery that led to a murder in February 1937.

Knapp wasn’t alone in the bank robbery. With him were his brother, Leroy, and a friend, Herb Allen. The three robbed the bank, but it was Stanley Knapp who “was the actual slayer in the bank robbery,” according to a wire story that ran in the Fairbanks Daily News on June 11, 1938.

While the men were imprisoned for the failed and fatal robbery, they attempted to escape. They beat a guard named A.B. Coleman on the head with a “rap” and tried to flee, but the “heroic jailer,” though “painfully injured,” helped prevent the escape and Leroy Knapp was shot in the abdomen, “probably fatally.” Two months later, Stanley Knapp was hanged. The fate of his brother and Allen is unclear.

In November 1941, a Spokane farmer named John Bruce Anderson, 52, was executed. Two years later, a 29-year-old Spokane cook named Chester Montgomery was hanged.

The 10th, and final Spokane man to be legally executed by the state was Woodrow Wilson Clark, a 30-year-old shoemaker called “Whitey” who murdered three people in a tiny apartment on East Sprague Avenue in 1944.

The night ended with a hatchet, but it began over pitchers of beer in the Rainbow Tavern, a bar that was still slinging beers and featured strip-dancing well into the 21st century.

T.P. Dillon and his wife, Flora, owned a sign painting shop next to the tavern and lived behind the store in a small apartment. One Friday afternoon, the Dillons went to the Rainbow and stayed until closing time, which was midnight in those days. A group of revelers went to the Dillons to continue the party.

The next morning, a young employee of the Dillons stumbled into the Rainbow Tavern.

“Go next door – around the back – see if you saw what I saw. It’s a massacre at the Dillons,” he told the bartender.

The police arrived and found three bodies hacked to pieces, and a bloody hatchet outside.

Several suspects had motives, including the husband of the murdered Jane Staples, 22, who was 33 years her senior. When police located Charles Staples, he had blood on his shoes. He said it was from a nosebleed. He was employed at the Armour Meat Packing plant, but the newspaper reported that he “did not work in the killing department.” He told police he knew of at least three men his wife had slept with, but professed innocence.

And there was the employee, who found the bodies. He had quit in anger the day of the murders, and his and the bartender’s footprints were the only ones at the snowy crime scene when police arrived.

Finally, there was Whitey Clark, a drifter from Maine with a limp who frequented the bars of East Sprague. He admitted to partying with the Dillons and others, and said he fried up an early-morning breakfast of bacon and eggs for the partygoers. He said he used the hatchet to split kindling for the stove. He ate and left at 2:30 a.m., he told police.

But the coroner had determined breakfast had been eaten at 4:30 a.m. and the murders took place a half-hour later, at 5. The coroner’s findings led police to question Clark’s truthfulness. They gathered up boys who delivered The Spokesman-Review in the area and had them look at a lineup, which included Clark. They fingered him and claimed to have seen him wandering down East Sprague, his sweatshirt stained red, the morning of the murders. Then police found Clark’s bloody clothes at a friend’s house.

Confronted with his clothes, he signed a confession.

He told police he was flirting with Flora Dillon. Her husband didn’t appreciate Clark’s overtures and pulled a gun. Clark hatcheted him to death. As Flora and Jane awoke to the sound of his murderous chopping, he took his work to them as well. A fourth reveler, Frank S. Winnett, received nine skull fractures, but survived.

Clark later said his confession was forced during an all-night interrogation.

“They stood over me and showed how the bodies lay on the bed and how I had hacked them and then hacked Winnett in the chair,” Clark told jurors. “I kept denying it, but they kept telling me I was lying.”

The jury was unconvinced of his innocence.

“The jury noticed Clark’s roving eye when a pretty woman entered the courtroom,” one juror said. The jury, it was reported, believed Clark went on a murderous rampage after Dillon thwarted his attempted rape of Jane Staples. He was convicted of the Dillon murders but never tried for Staples’ death. He appeared “almost stunned” by the verdict, according to a March 20, 1944, article.

He was hanged at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla on Feb. 4, 1946.