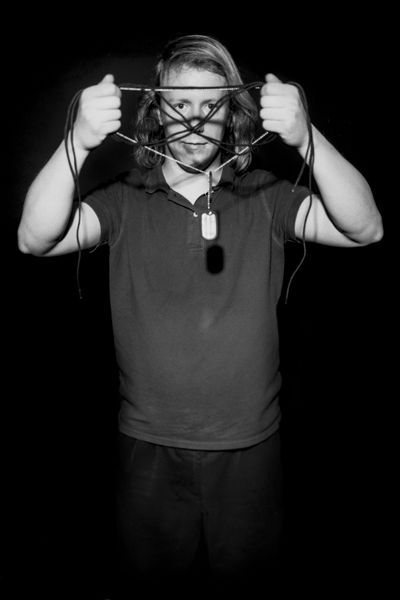

Survive: Paul

He’s standing firm, smiling gently and holding his dog tags in such a way that they almost frame his face.

He’s also holding a spare pair of shoelaces, the ones he had planned to use to end his life when he was in the service.

Both, he says, are symbols of his personal journey. His time in the U.S. Navy plays a big role in his growth as well as his struggle. In many ways, he says, he found himself in the service. He almost lost himself there, too.

Paul Ramer enlisted at 23, completed boot camp at 24 and served four years. He “felt a sense of pride being in the military.” But, he also says, “I have ambivalent feelings about my time in the service. Some of the best things happened to me and some of the worst.”

First, the good. He learned he’s smart and a fast learner, that people liked and respected him, including his superiors. He gained self-confidence and became more outgoing. “I felt like I now had a purpose in my life.”

Next, the rest. Foreign language school was intense and stressful, and he fell behind. He was angry and embarrassed, became quiet and disenchanted, kept to himself, felt isolated and ashamed. Depression crept in. So did lethargy. Somewhere along the way, he lost his religion. “The biggest thing was the sense of failure,” he says. “It’s demoralizing.”

Sometimes, he says, someone would ask him if he was OK. “I’d say, ‘I’m fine,’ but I wasn’t. And no one went any deeper. I showed some outward signs. I was hoping someone would notice. If someone had just followed up, took me aside, sat me down, said, ‘Hey, I’m concerned about you.’ … ”

Paul took suicide prevention training in the Navy. So, he says, “I was very aware of my own decline. I could identify the symptoms. I knew where it could go. It got more and more serious.”

The laces were meant for his military boots. A back-up set. But, he says, “I started seeing their potential.” He tested the metal hook on his door. Would it hold his weight?

“I was making a plan,” he says. “I tried to make sure it was foolproof. Had I made it work, I probably would’ve been dead that same day. Because I couldn’t get it to work, I put it off. I procrastinated.”

He didn’t talk about it. He held it in for about three years and only just started talking about his experience about two years ago. He’s participating in the project in hopes that it fosters more communication.

“I know how bad it feels. The isolation. I don’t want anyone to go through what I did.”

He keeps the pair of laces as “a reminder of where I’ve been and what I haven’t done. It’s a reminder of something I could’ve done but didn’t do, and it’s a reminder that I don’t ever want to be there again.”