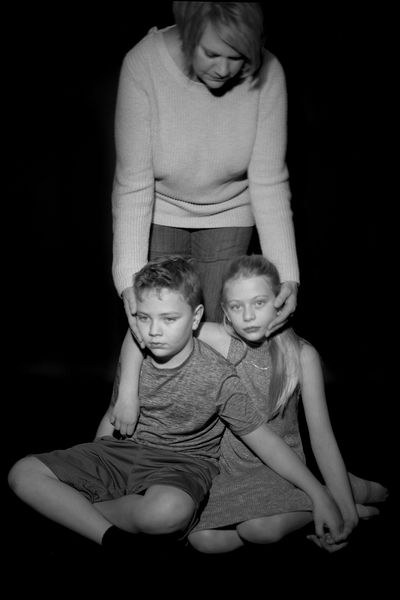

Survive: Diana, Meg, Knox and Hunt

She’s standing behind them, watching over them, cradling their faces, one in each of her hands. Her children sit on the floor, holding hands. The girl has her arm around her younger brother.

This is, their mom says, a picture of love and support.

“I just want them to know I’ve got their backs. I’m supporting them and loving them and trying to help them through this.”

Meg is 11.

Knox is 9.

“I’ve tried so hard to teach the kids that there is no shame in the way their dad died. We don’t need to hide. We don’t need to feel embarrassed or shame. I tell them, ‘Your dad died because he was sick.’ It was truly an illness that took him. He loved life. I know the depth of our love and our life together.”

Diana and Hunt Whaley were married nearly 14 years before he died by suicide last August. The neighbors heard the gunshot.

“He had a personality that was larger than life,” Diana Whaley says. “He was an attorney with the city. He was successful. But he was ashamed of being mentally unstable. The more we talk about mental illness hopefully the stigma surrounding it will decrease.”

Diana Whaley met photographer Grace June at Spokane’s 2017 Out of Darkness Walk, not quite two months after her husband and father of her children died.

“We were still in shock,” she says. “We didn’t sign up for the walk. We didn’t plan on participating. But I wanted to take the opportunity to take the kids to something and show them we’re not alone. There were many connections made that day, but Grace was the first. I thought her project sounded beautiful.”

The family posed for their portrait later that fall. June let them into the dark room to watch the photos develop.

“Watching them come to life was just beautiful. It gave the kids and I another moment to have another conversation about it and the grief around it,” says Whaley, who wrote a letter to Spokane Arts in support of June’s grant application.

She chose letters her husband wrote to their children earlier that year to accompany their portrait at the exhibit. She plans to be there with both of them.

“I want to expose them to different outlets to handle their grief. I just don’t want them to internalize it. I’m trying to help them heal. We need to keep on this. We need to talk about it. We need to continue the story.”

Their portrait is a way to help them do that.

“To be able to physically hold grief in your hand and connect with it, I think, is powerful.”