Mixed materials: Garbage in the recycling is messing up the industry

On the concrete floor of Inland Empire Paper sat a 1,500-pound bale of waste paper ready to be recycled into new paper.

The bale came from a modern single-stream recycling system that takes mixed-up recyclable materials collected at the curb and sorts them out by product.

Inland Empire Paper allowed The Spokesman-Review to hand-sort the bale of what was supposed to be only paper. After hours of hand sorting the contaminants – plastic bags and bottles, pruning shears, shoes, diapers and wads of human hair – two piles are left: one of recyclable paper and cardboard; the other, everything else.

The results of the sorting highlight the top problem facing modern recycling systems: The materials that most certainly could not be used to create new paper amounted to about a third of the original bale.

Inland Empire Paper – a subsidiary of Cowles Co., which also owns The Spokesman-Review – said the bale was not from Spokane’s recycling system, which is run by Waste Management, but from a system much farther away that offers the most-pure paper bales they’ve been able to find. (They declined to name the system, citing a need to protect its business interests.)

Inland Empire Paper is one of the last two newspaper processing plants in the county that still uses recycled fibers, according to recycling consultant Bill Moore, owner of Moore & Associates, a recycling firm in Atlanta. In most cases, the post-recycled paper is too contaminated to be reused, he said.

Waste Management, the national conglomerate responsible for collecting, sorting and selling Spokane’s recyclable materials in a facility on the West Plains, is dealing with similar contamination issues because of the single-stream system that sees Americans dump all recycling into one bin, leaving it up to the collectors to sort it back out. It’s a relatively new practice. “Sorted” recycling, which placed the responsibility of separating the stream on individuals, has been phased out of most larger cities.

When Spokane switched to single-stream recycling in 2012, city officials heralded the move as a money saver and a way to recycle more paper, plastic and metal, while at the same time easing the burden on residents.

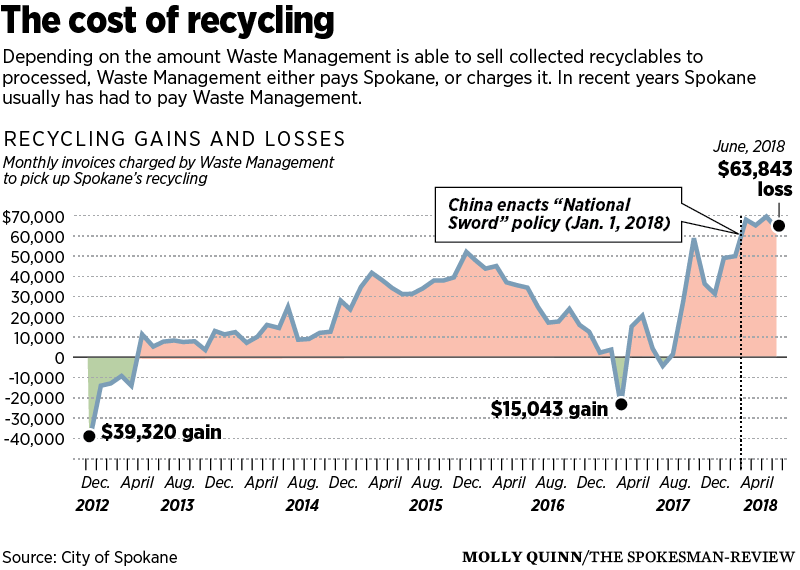

In the new system, if Waste Management is able to make enough money selling the materials it sorts to be recycled, it pays Spokane. Spokane estimated it would collect about $35,000 a month, according to a 2012 article in The Spokesman-Review.

But most months since the city moved to single-stream, the market for recyclable materials has been so bad, Spokane instead has had to pay Waste Management. In some recent months, Waste Management has charged the city as much as $60,000 a month.

Even with those payments, the city says it is still ahead financially, as the new system allowed it to cut recycling jobs and reduce its truck fleet in 2012.

But earlier this year, a major roadblock fell in the path of the country’s recycling industry. Previously, China had been the biggest buyer of U.S. recycling. Most of the country’s newspapers, cardboard, plastic bottles and aluminum cans were sent to China. After years of accepting highly contaminated bales of goods to recycle, they stopped Jan. 1.

The U.S. recycling industry is feeling the consequences. Nationwide, single-stream collectors are struggling to sell their recycling, contaminated as it is with nonrecyclable materials.

Adapting to this new reality comes at a cost. The city of Spokane is paying record amounts to get rid of its single-stream recycling, while Waste Management says it is investing in its sorting system, and has had to lower the price of the material it produces.

Still, Spokane – which has other markets, and did not depend heavily on China to purchase its recycling – is faring better than many other cities, said Waste Management spokeswoman Jacki Lang. Seattle’s recyclables processor, Republic Services, had to dump “hundreds of tons” of mixed paper to landfills in March, according to the Seattle Times.

Other municipalities in King County have their own contractual relationships with the processors, which could allow some of those municipalities’ recyclables to be sent to the landfill, depending on the decision of each municipality, according to Mary Kelley, spokeswoman for Seattle Public Utilities.

Adapting to a new reality

Waste Management’s sorting plant is located near the airport, in a three-story tall recycling sorting plant. Inside, a machine takes in single-stream recycling – a mixture of plastic, paper, aluminum and glass. Workers pull out contaminates, air blowers sort paper and claws grab and filter plastics.

The recycled material that Waste Management receives is about 10 percent nonrecyclable trash, Lang said. In contrast, China’s new requirement allows for the purchase of material that is 0.5 percent or less contaminated.

Waste Management is responding to the changes in the market by slowing down the process and adding more people to the sorting lines, Lang said.

“We face new and intense pressure related to contamination and pricing,” Lang said.

Inland Empire Paper is having to reduce its dependence on recycled paper because of the amount of contaminants in the bales.

In a statement, IEP said that “single-stream collection has resulted in continually increasing contaminant load,” creating “a real threat to the future of paper recycling at IEP.”

Recycling and solid waste rates for residents of Spokane are set for the next three years. Rates won’t increase above 2.9 percent over that period, city spokeswoman Marlene Feist said, but after that, there’s no certainty.

As of now, the rising costs of recycling have been absorbed by the solid waste budget, but Feist said the city is doing whatever it can to help the industry and not pass on the costs to taxpayers.

“We’ve been concerned about it for a while,” Feist said.

A ‘short-term crisis’

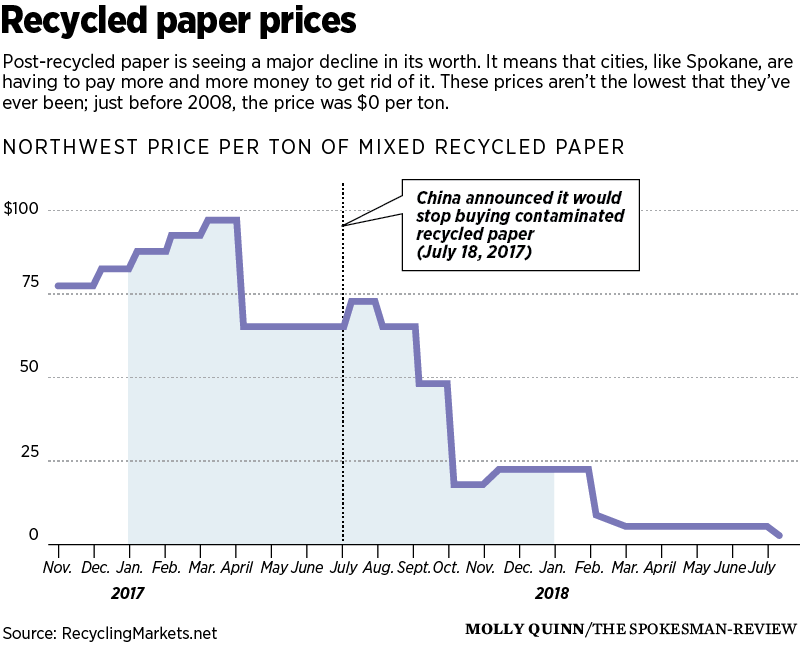

In July, the price of mixed paper in the northwest was $1.50 per ton, according to Recycling Markets Ltd.

A year ago, it was worth about 50 times that amount.

But July’s price isn’t the worst it’s been, said Robert Boulanger, president of Recycling Markets Ltd. In 2008, just before the economy crashed, the cost of one ton of recycled paper was zero dollars, he said.

“Contamination restrictions have got too lax over the past five or six years because China was taking it all,” he said. “It’s in a short-term crisis.”

In the long term, Boulanger said, domestic paper mills are going to have to hire more workers and build more equipment to sort the recycling. Many recycling plants shut down over the past 10 years because of China’s appetite for material, but now, more recycling plants will be sprouting up in the states to handle the load, he said.

Was single stream

a mistake?

It’s unlikely that Spokane will switch back to sorted recycling collection, said Alli Kingfisher, a materials management and sustainability specialist with the Washington Department of Ecology. She hasn’t heard of one company in Washington that has.

“The switch to single stream is a balance of quantity versus quality,” she said.

With China taking the majority of recycling before this year, single stream was the best choice, she said. But now there is more quantity than the domestic market can handle, driving down prices of recycled goods.

“Was it a mistake? At the time there was a market for the material,” Kingfisher said. “Now there’s not.”

Ed Humes, author of “Garbology,” a book that explores where Americans’ recycling goes, said the waste-producing public needs to fix the “illusion of recycling” – people’s ambition to put trash, like plastic bags, in the recycling bin and feel good about it, out of sight and out of mind.

China’s decision to stop accepting U.S. recycling will force us to clean up our own recycling and, in turn, use more of it, Humes said.

“Long term,” he said, “it’s a good thing.”