Some Seattle-area recycling dumped in landfills as China’s restrictions kick in

Yellowing newspapers, junk mail and scrap paper, bundled together in blocks as big as a compact car, are stacked three and four high in nearly every available corner of the largest recycling facility in Seattle.

Rows of these mixed-paper bales also sit out in the rain and wind, sodden and sagging like their value now that China, which was by far the largest and most important market for this commodity, has shut its doors.

Republic Services, which processes recycling from Seattle, Bellevue and other cities in King County, has sought permission to send some of this unmarketable paper, fast becoming mush, to regional landfills. The company cites safety and health risks as the bales pile up in the Sodo facility designed to send out as much as it takes in — about 750 tons — each day.

“Regardless of price point, we haven’t been able to move material on a daily basis,” said Pete Keller, Republic’s vice president for recycling and sustainability.

Even as Republic finds new markets and installs equipment to meet new quality standards, the company has sent “hundreds of tons” of mixed paper to landfills, including its own outside of Roosevelt, Klickitat County, over the last couple of weeks, Keller said.

That’s a relatively small amount in the bigger picture of the region’s standout recycling system, but it’s the most visible local repercussion so far from China’s new National Sword policy, which was announced last summer and took effect Jan. 1. China instituted outright bans on some recyclables, including mixed paper, and heightened quality standards that the Washington Refuse and Recycling Association describes as “all but unachievable with current equipment and system costs.”

The impact will likely show up on ratepayer bills before long, as commodity prices plummet and costs to process recyclable materials increase, say local government and industry officials.

Despite the changes roiling recycling markets, recyclers here are sending a consistent message: People should continue recycling and consider upping their game to help meet new quality requirements. That means reducing contamination from food and liquids — containers should be empty, clean and dry when placed in the cart — and letting go of “aspirational” recycling. That’s when people try to recycle things they think should be recyclable but aren’t. People can check with their cities and service providers for up-to-date lists of what should go in the recycling cart.

“We’ve spent decades and decades educating the public about the value of recycling and what goes in what bin,” said Heather Trim, executive director of Zero Waste Washington. “We definitely don’t want to go backwards on that.”

Improved consumer and business practices will help recyclers as they tap new markets and try to reopen sales to China.

In the short term, recycling companies have sent mixed paper to buyers in India, Malaysia, Vietnam and South Korea. But these secondary markets have nowhere near China’s appetite for recycled paper, creating a global supply-demand imbalance that has driven down prices.

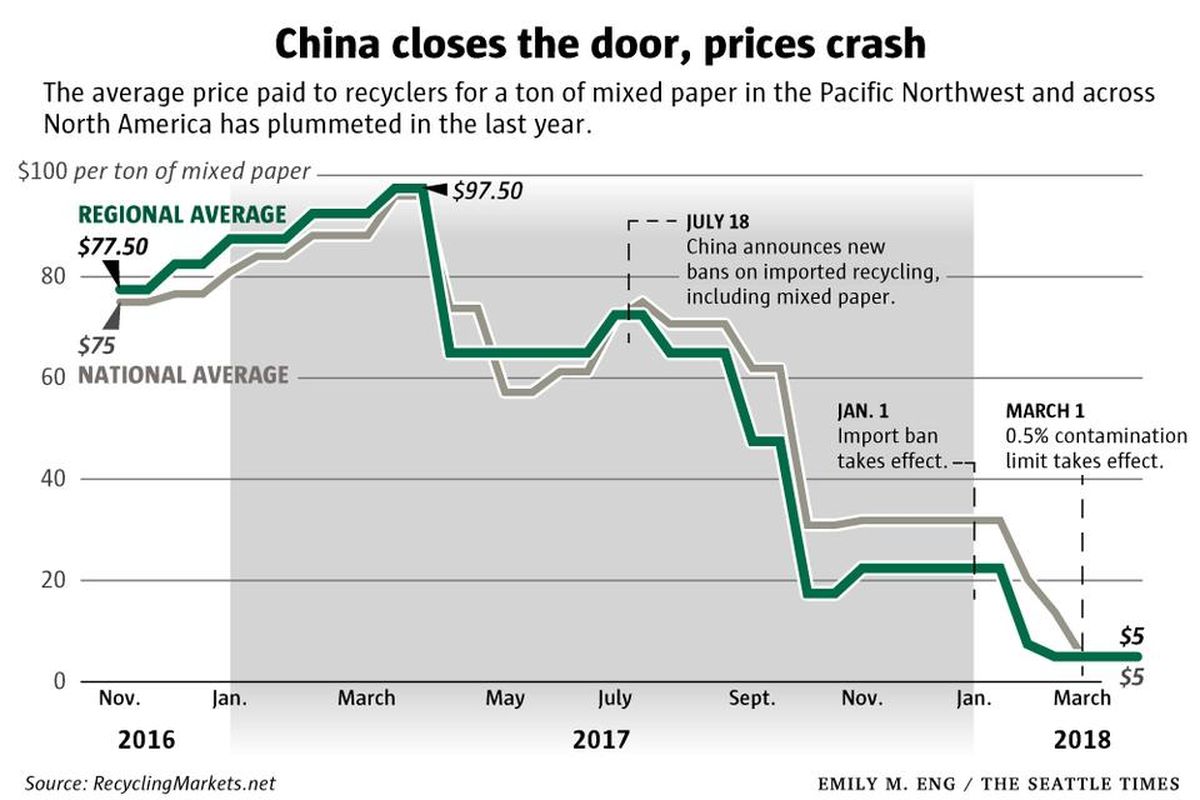

The average price paid to recyclers in the Northwest, including British Columbia, has plummeted in the last year from $97.50 to $5 a ton as of mid-March, according to data from RecyclingMarkets.net.

The new Asian markets also come with higher costs for processing and shipping — recycled commodities bound for China were shipped at low costs by sending them in empty shipping containers returning from West Coast ports — and there are questions about their long-term viability.

Although less attractive than China, the presence of these secondary markets — which have been tapped by recyclers including Recology and Waste Management — prompted the city of Seattle to deny Republic’s request to send materials collected in the city to landfills.

“Markets are challenging, but there continues to be opportunities to move the specific commodity, mixed paper,” said Hans Van Dusen, Seattle’s solid waste contracts manager.

Seattle accounts for about 40 percent of the material sent to the Republic recycling plant in Sodo for processing.

Republic says most of the other cities it serves in King County have granted it temporary authorization to send deteriorating mixed-paper bales to landfills. Bellevue, for example, gave Republic permission to do so until April 20 in recognition of the China market disruption, said public information officer Michael May with Bellevue Utilities.

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality has also granted waivers allowing some recyclables to be sent to the dump.

Republic executives say sending recyclable materials to landfills is a worst-case option to deal with an unprecedented situation. Environmental concerns aside, it’s usually more expensive to dump it than recycle it, even at such low prices.

Most recyclers are for-profit businesses and will seek to pass on their increasing costs. The state Utilities and Transportation Commission (UTC), which regulates what solid-waste haulers can charge for services outside of areas covered by municipal contracts, is already fielding rate- and contract-adjustment requests, said Danny Kermode, the commission’s assistant director for solid waste and water.

Representatives of both Recology and Waste Management indicated they may seek rate increases from the cities with which they contract. Waste Management has already initiated a request at the UTC. Republic said it is still weighing its options.

“We need to more closely associate the costs of recycling in customers’ minds with what is actually happening,” said Kevin Kelly, general manager of Recology, which provides recycling and collection services locally to cities including Shoreline, Bothell, and Burien, and operates a materials-processing facility.

Republic’s Keller and others in the recycling industry think Chinese paper mills will eventually accept recycled paper from the U.S. again. But recyclers will need to meet new quality standards. China now demands much lower levels of contamination — no more than 0.5 percent — for materials it is accepting, including cardboard and newsprint.

“That’s much cleaner than what most of these systems are set up to produce,” Keller said.

At Republic’s Lander Street facility in Sodo, which handles recycling collected by its own trucks and by those of its competitors, the sorting process begins with an undulating ocean of everything people place in their blue or green recycling bins, including many things they shouldn’t. This pile is gradually fed into a maze of conveyor belts that run over, under and through a series of screens, blades, scanners, fans, air jets and magnets that separate cardboard, plastic, metal, glass and paper. About 50 people work amid the machines, picking out by hand items missed by the technology.

This week, Republic is installing a new optical scanner, which it says is the first of its kind in the country, specifically aimed at reducing contamination in mixed-paper bales, and doing so at high speed.

“The other way to do better quality is manual labor at low speed,” Keller said, but that can reduce the capacity of a facility, which each day has to confront another wave of incoming recycling.