Jason Colby’s ‘Orca’ offers personal and historical perspectives on orca captures

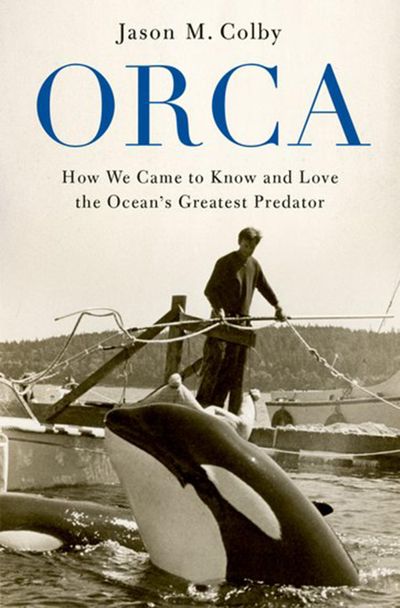

Jason Colby has more than a historian’s perspective on the era when orca whales were trapped and sold for profit and entertainment all over the world: His father used to be a “cropper,” as the fishermen of these great mammals of the Northwest called themselves.

Today an associate professor of environmental and international history at the University of Victoria, Colby, author of “Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator,” was born in Victoria, British Columbia, but raised in the Seattle area, where he worked as a commercial fisherman in Alaska and Washington. His is a Northwest story, born and bred, and he tells it with the depth and passion the topic deserves.

“My family lived with this story,” Colby said in an interview, explaining his father had been involved in a capture, but quit the business after three of the whales later died in captivity.

“The book is trying to take us further back, to help us explore how we came to care about these animals in the first pace. It starts at reminding Northwesterners that live captures were not the worst thing that happened to killer whales. Up through the mid-1960s, locals regularly shot and killed killer whales. They were seen as this kind of vermin species, the same approach we took to land predators like wolves. And the only way they studied them in the 1960s was to kill and dissect them.”

Captive orcas, netted in Northwest waters and especially Puget Sound were sent all over the world from Seattle in the 1960s and 1970s before state and federal laws finally shut down the practice. But it was captive whales, Colby argued, that provided the understanding of the species that led to the ethical imperative to save the whales.

Colby’s book comes out just as the Lummi Nation is campaigning for the release of the last southern-resident orcas still surviving in captivity.

Lolita, a member of L pod, was taken when just 4 years old in 1970 at Penn Cove and has been in captivity ever since at the Miami Seaquarium.

Colby argues that while he is sympathetic to her plight, it should illuminate not only the tragedy of what happened to her, but the existential threat every member of the J, K and L pods faces today in the wild because of the degradation of their home waters.

The people of the Northwest and beyond have a moral obligation to save a species that single-handedly educated the world about the true character and marvel of the species, Colby said.

“I would argue that we have a debt to the resident killer whales. We have a moral obligation to this population that helped transform our views of cetaceans. We owe it to them to protect them. They helped make us better people.”

His detailed history of the era of capturing orcas for theme parks and cutting them up for research is painful, even excruciating, reading. Orcas are tangled and drowned in nets. They die on planes in undersized crates packed with insufficient ice. An orca is lifted by its tail for transport, breaking its back. Whales are branded, shot and separated from their families, screaming as only an orca can scream in terror.

Once corralled, captors easily picked off the whales they wanted, because the families stuck together, trying to help one another, rather than fleeing the melee.

Colby’s nonetheless is a respectful portrait of the captors, who operate in another historic and moral context, that their own deeds helped transform.

Ultimately though, this son of a cropper saves his purest sympathy for the animals themselves, now critically endangered, with a population of just 76 southern-resident killer whales left, dependent on salmon runs also depleted as their home waters are degraded by people.

“In its preindustrial state, this coast was ideal for specialized predators who fed on fat, abundant chinook salmon,” Colby writes. “But . the Salish Sea was becoming an urban, saltwater lake – increasingly loud, empty and polluted.”

Today the biggest threat to the orcas is no longer live captures, Colby writes. It is us.