‘Won’t You Be My Neighbor?’ is poised to be a hit, and it might help redefine the meaning of ‘Christian film’

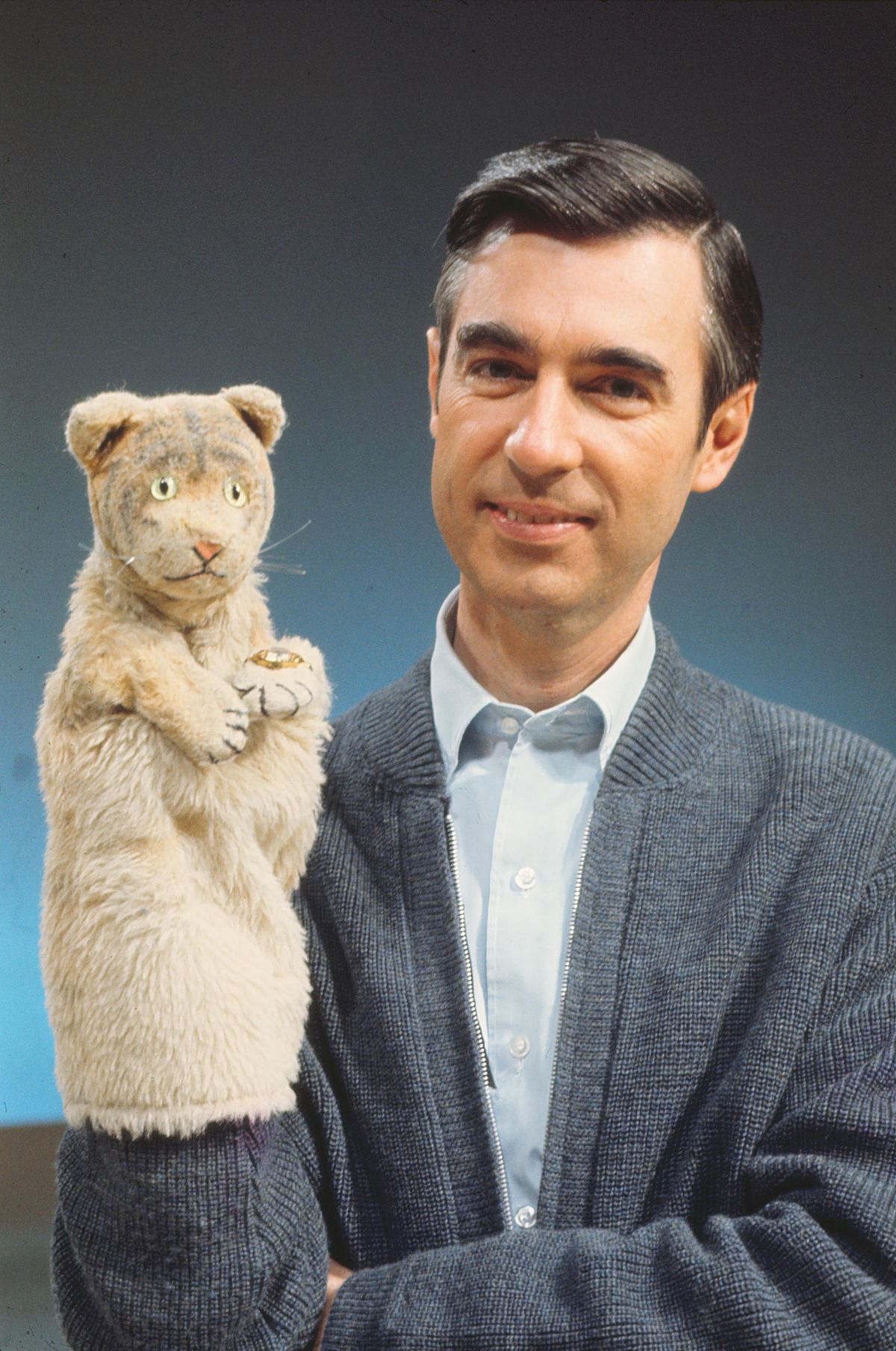

Mister Rogers is most famous as the sweater-clad television host who pioneered children’s programming and, in later years, became America’s unofficial comforter-in-chief. Now, 15 years after his death, he might be helping to rebrand Christian film.

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” a new documentary about Rogers’s life and career, is finally arriving in theaters after becoming a sniffle-inducing sensation at the Sundance Film Festival in January. As a collection of archival material, astute talking heads and snippets of interviews with Rogers himself, Morgan Neville’s film isn’t explicitly Christian. But as a portrait of an ordained Presbyterian minister who saw children’s television both as his spiritual vocation and as a powerful means of evangelism, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” delivers an unmistakable message, both in its depiction of pastoral service and its celebration of compassion, mutual respect and love at its most radically unconditional.

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” – whose trailer has been viewed an astonishing 3.5 million times on YouTube – may well join “RBG” as a documentary hit of the summer. And it will demonstrate yet again that there’s an underserved Christian audience that is far more discerning, variable and open to being challenged than the conventional faith-based market realizes.

So far this year, that market has seen one bona fide hit: “I Can Only Imagine,” the dramatized story of how the song of the same name came to be written, has earned an impressive $83 million in theaters, doing particularly well with evangelical audiences. But traditional Christian movies have also seen some slippage. The third installment of the “God’s Not Dead” series, for example, was greeted by a box office take as dismal as its reviews.

Meanwhile, an entirely different kind of movie is finding purchase with spectators who shy away from the twin poles of sentimentalized complacency and grievance that have historically defined Christian filmmaking. Although the New Testament-based drama “Paul, Apostle of Christ” earned just slightly more than $20 million, it represented an aesthetic leap forward in biblical storytelling in production values, acting prowess and themes of self-sacrifice and resistance.

“First Reformed,” Paul Schrader’s rigorous, often deeply unsettling portrait of a pastor wrestling with spiritual doubt, is poised to become an art-house sensation, drawing filmgoers eager to witness the triumphant comeback of the man who wrote “Raging Bull” and “Taxi Driver,” and to watch Ethan Hawke deliver one of the finest performances of his career. “Pope Francis: A Man of His Word,” is similarly positioned to become a hit with international audiences, especially Catholics.

As “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” makes its way to theaters, a large part of the audience will be the secular “youngs and Nones” who have either left the church or never joined, not to mention nostalgic baby boomers and Gen-Xers who harbor abiding affection for Rogers as the surrogate confidant of their youth. But just as many will be practicing Christians who are eager or at least unafraid to grapple with their own commitment to faith and spiritual practice, but find themselves alienated by the pietism, naivete and clumsy sermonizing of films that seek either to stir them into a self-victimizing frenzy or reassure them with soft-focus uplift.

Erik Lokkesmoe, a former speechwriter in the George W. Bush administration, formed the marketing company Different Drummer with two friends 10 years ago to raise awareness of movies that live where faith, intellectual challenge and artistic sophistication happily reside. (He worked on such films as “Calvary” and Terrence Malick’s “Tree of Life.”) A few years ago, Lokkesmoe helped form the production, marketing and distribution company Aspiration Entertainment, where he distributed the biopic “Noble” and executive-produced “Last Days in the Desert,” starring Ewan McGregor.

Having signed on to help support the marketing campaign of “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” with faith-based audiences, Lokkesmoe is optimistic that the film will connect with what he calls the “middle space” of filmgoers, a cohort he estimates to be around 15 million in number. These viewers reject both the “mass and crass” sensibilities of the general movie marketplace and the “teach and preach” approach of traditional Christian films. Lokkesmoe is convinced that the way to appeal to his audience is through what he calls “heart and smart.”

Lokkesmoe compares “The Passion of the Christ,” “God’s Not Dead” and similar “event” movies to a downpour, which might create a momentary sensation but leaves little of value in its wake. By contrast, he calls films like “First Reformed” and “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” examples of the “droplet” strategy.

“It’s like this steady drop of good storytelling, thoughtful, conversational art,” he says. “It’s for smarter, more soulful audiences who want to go see something that’s worth two hours of their time and worth putting their cellphone down.”

Unlike downpour movies, the droplet audience is younger, and not inclined to attend screenings organized by churches that buy out entire theaters to make a point. Instead, Lokkesmoe observes, they’re “pushing back on the confirmation movie, where you go to a movie not because it’s good or you feel that its themes resonate with you or you want to be challenged or have a haunting experience after the credits roll. It’s more, ‘My friends are going, my church asked me to go, and I’m going to go out and support this statement so that we can win, we can dominate.’”

Rather than domination, middle-space filmgoers crave reflection. Instead of winning, they welcome the chance to grapple with eternal questions of faith and forgiveness, hopelessness and grief. So far, this summer’s movies are providing ample opportunity to do both – and amen to that.