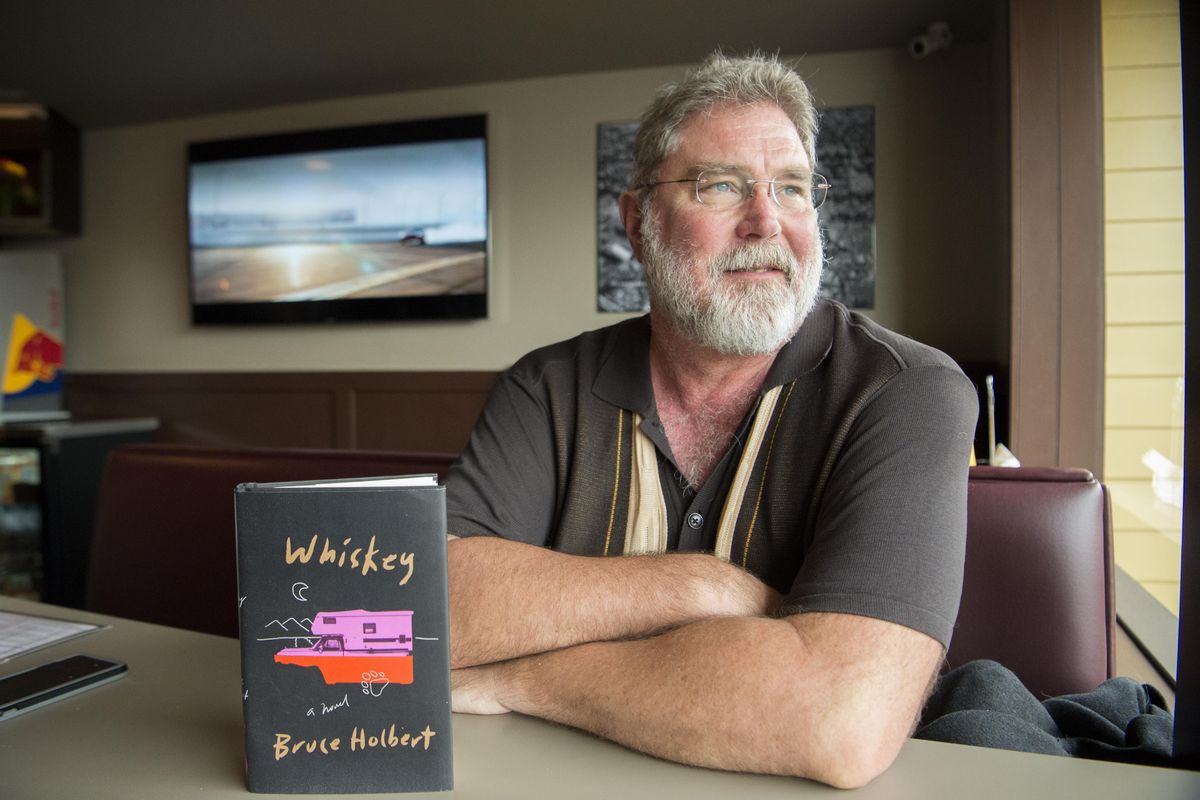

Summer Stories: ‘Let the Dogs Drive’ by Bruce Holbert

Both are American Staffordshire Terriers aka pitbulls. So, strike one, though the two consider themselves lap dogs. George takes his cue from Martha and she wouldn’t harm a soul unless they’re a threat to the kids. I worried when the kids roughhoused she’d get confused and tear them to confetti. But she knows war from play and would only roll and grin dog grins when the children pulled at her ears or bombed the two of them with balled up socks. But when the wife left with the kids, she told the judge the same dogs that protected them from birth had become a danger. Once, in a drunken fury, I stapled the wife’s picture to a pork chop and deposited in their dish. Both dogs ate the meat, but let the photograph be.

I lost my job at the parts store not long after the family exited. A damned country and western cliché: lost the wife, lost the kids, lost the job and now the dogs. Except the parts place rehired me, though reduced the hours, which turned the Safeway meat counter out of the question. So, for the last nine months, I occasionally shoot a deer despite the season then butcher it in my cousin’s garage. After, I stow the packages in my deep freeze beneath frozen vegetables and TV dinners and other legitimate groceries. I swap jerky with a widow who cans vegetables and fruit from her yard. At first I thought I’d slipped into some primitive half-man, half-ape status. But in truth nothing much differed.

Children had been my idea, the wife claimed when we argued. I hushed her; they might hear. It’s true I admit. I wanted babies. No reason, really, other than I enjoyed children. They amused me. I remained secure with them and certain of myself. I didn’t shrug them off when they interrupted; I entertained them even when my friends grew exasperated with their babble or histrionics.

Now the children are a hundred miles away because a judge says so and with a woman who employed them as leverage. Now judge wants the dogs, too. What was their crime? Well, they bark. Why? Because they wandered once and the judge ordered them fenced. So they bark at what’s outside the fence. The neighbors fear them. Old Carlson raises chickens and someone convinced him to sacrifice a hen that quit laying for a greater good. Candy Reynolds, a fat busybody, killed it with a rock (Carlson didn’t abide blood), then lobbed it over my fence. I returned from my shift, and feathers and bones and George and Martha’s bloody smiles are what remained.

The cops will not take my dogs. I sold the furniture to the thrift store, emptied my paltry savings and secured the hunting camper atop the pick-up. A gym bag of bullets and the guns I stowed beneath the seat. In the glove box was $2,827 and in my wallet three credit cards; two nowhere near maxed out. And where will they send the bills? The wife’s place is my forwarding address.

I drove 400 miles, bound for the ocean. We covered the scablands, a desert and Moses Lake (the current residence of my family – we didn’t stop), then climbed a high plateau, descended to the Columbia River then rose and descended once more before we entered the mountains. The day had cleared and blued and above us from the river on was the great round peak of Mount Rainier. Disconnected from the horizon by low clouds, it hovered like a god. The dogs though didn’t notice, though I pointed through the windshield. Instead of looking, too, George licked my extended finger and Martha dropped her head in my lap.

The mountain I knew was there and they didn’t. Being a father was pointing toward what your kids didn’t yet see, then at some point, they point and you squint. The dogs would never get that far. Maybe that’s my affection for them. I can remain in one place, father, alpha.

At the ocean, the dogs clambered from the cab, then froze. They had never witnessed such an expanse of one thing. I walked through the parking lot to the sand. They followed glancing at one another for assurance. Once in the sand, I jogged and the dogs, tongues and tails awag, loped beside me. The waves expended themselves on the sand, the sound omnipresent as breaths. But the dogs barreled into the water and the noise with a child’s joy, I recognize not because I recall such elation, but because I had recognized it in my own children. The animals frolicked – that’s a word I never use, but it’s the only one that applies. They bit the wave crests, snorted when the water filled their noses, paddled when they ventured deeper. Tourists interrupted their wading and sand castles to watch. For an hour the dogs threw themselves at the ocean. Worn out I figured, they followed me to the camper and food and fresh water. But after, I fed them, the two whined for a second swim that took us through sunset into full blown night when the dogs’ noses and ears and tails cut the water like fins in the moonlight.

That night the animals slept like champions, their snores rhythmic as the back and forth of tides. Late, restless, I hunted my phone and music, which I played quietly aloud.

I passed on “Sweet Home Alabama” and “The Strawberry Roan” and several others. I could have scrolled for something that suited me, but I avoided intent. Soon the songs appeared like prophecy: “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Superstar” (Carpenters not Sonic Youth), “Rainy Night in Georgia,” “I Fought the Law” (the Clash), “Satisfaction” (Devo), “One Tin Soldier,” “She’s Gone,” “Teach Your Children,” “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo” and “We Are The World.” Then “Short People” by Randy Newman, and that was prophecy, too. I switched off the phone.

The next morning, I set out early. The dogs dozed until noon when we halted for lunch then proceeded to the mountains. It had turned hot on the coast and I desired a respite. We ended up beneath Mount Adams. Snow clung to the shadows that resisted sunlight. It was not the peak Rainier was, but tourists had not discovered the place. I halted at one of several bars on the worn highway, because two saddled horses were snubbed to a porchpost. Inside, I used the restroom and purchased a Bud King Can, 24 ounces.

Exiting the place, three boys leaped for the my truck windows. The dogs stared out. I opened the passenger door. Martha lowered her head and sauntered toward them. The youngest patted her and she gazed up, her tongue lolling, her grin. The oldest joined him. The middle boy appeared lost until George whined and rolled and the boy patted his belly and he too panted in pleasure.

A woman approached. “Shouldn’t those dog be leashed?” she cried.

The children’s father stared hard at her.

“You never know,” the woman said.

“Mind your own business,” the mother told her.

The children continued to enjoy the dogs and the dogs the children and when it grew time for the family to move on I grew sadder than I had been in years, maybe ever.

The dogs, too, seemed subdued. They labored into the pickup, tired. I found myself crying. Dogs and children, well something is sacred between them. I filled the truck with gas at a grocery. After, I fried all the meat and the dogs and I ate past healthy, stowing the excess for coming hungry days.

Midnight, I reached Moses Lake and parked the camper a few blocks from the wife’s. I hunted a rope and looped it through George and Martha’s collars. The dogs glanced at me but didn’t seem concerned. The wife’s yard was well-kept, annual flowers beneath the windows and the grass fresh cut. Martha slowed and so did George. They sniffed the lawn and the flowers. In my wallet were pictures of the kids. The wife’s remained in the yard at home with the pork chop bone. The dogs approached when I whispered the children’s names. I showed them the pictures. Martha pressed her nose against one and lapped it with her tongue. George sniffed, too. The wallet could have smelled like meat, it could have smelled like me, it could have meant nothing. You may find it ridiculous, but I choose it to mean what I desire it to. I tied the rope to the wife’s porch and pinched between the screen door and the one locked to me an envelope: $2,000 from the glove box and a note: It’s not the dogs’ fault.

Author’s note: I kept trying to make the dogs monsters but they wouldn’t be monstrous, so this story is for Sharma Shields.