John Blanchette: Though the voice for college football fans across the country, Keith Jackson’s heart never left Pullman

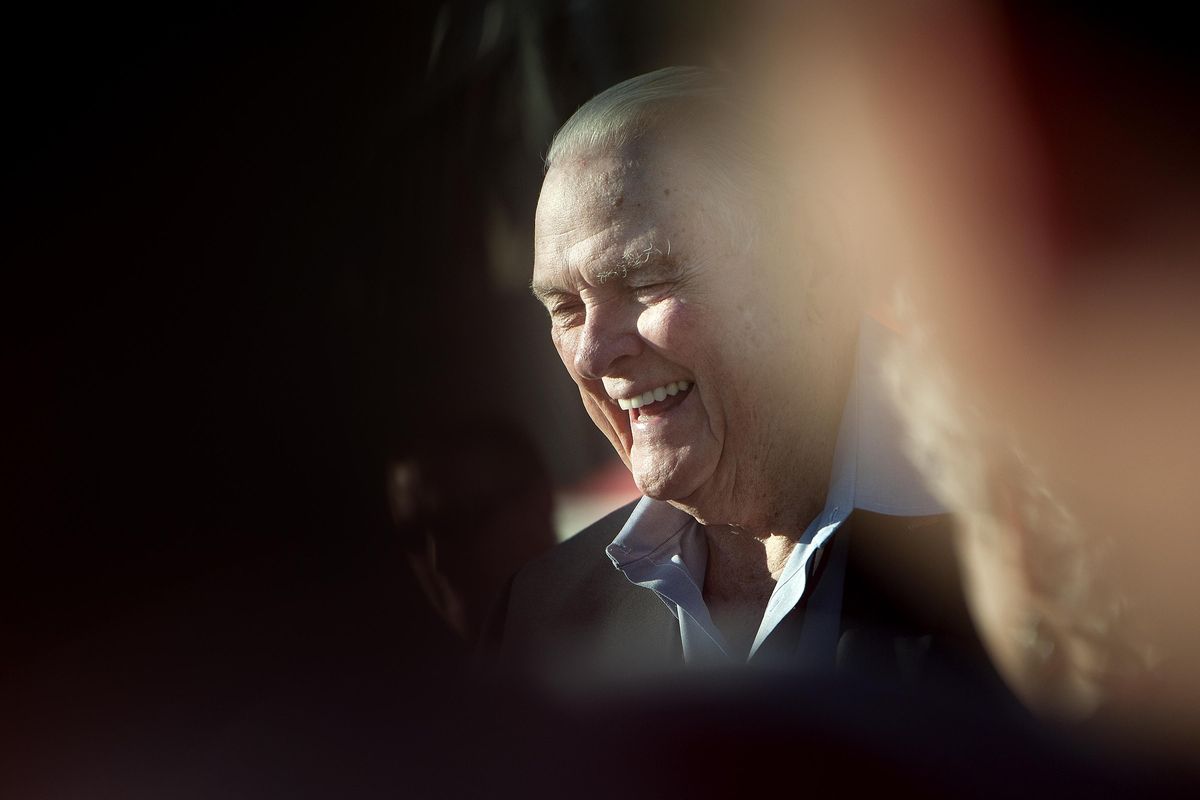

Legendary sports caster Keith Jackson was all smiles after he raised the WSU flag before the the first half of a college football game against Portland State on Saturday, Sep 13, 2014 at Martin Stadium in Pullman, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Keith Jackson started calling football games as a boy shucking corn in his grandmother’s barn and … well, never left.

He retired, yes.

But until that point in 2006 when he finally shucked his headset for good, if you switched on the TV on an autumn Saturday and heard Jackson’s modified Georgia twang you were certain there was straw on the floor of his broadcast booth and a milk cow standing next to him.

It’s the way college football was supposed to sound and feel, and it just flat doesn’t anymore.

So in that respect, Jackson’s passing late Friday night – in his genteel, respectful phrasing no one would have ever “died” – allowed those who grew up with football accompanied by his soundtrack to remember the best times.

Though as he would often point out off-mic, those times were never as innocent as we prefer to imagine.

On mic? Any editorializing was kept to a minimum. Keith Jackson wrote his own job description and it was simple: “Educate, illuminate and then get the hell out of the way.”

Commendable, but not precisely on point.

The greatest broadcasters have the knack for marrying their narration to the moment without stepping all over it, and this was Jackson’s special gift. You have to think only of Desmond Howard’s magical punt return in the 1991 Michigan-Ohio State game and Jackson’s minimalist caption: “Goodbye … hello, Heisman!”

When Howard struck the trophy pose in the end zone just a couple of beats later, you had to wonder whether Jackson’s call was being piped into the player’s helmet.

It was just another instance of Keith Jackson being the voice every college football fan had in his ear.

But he was Washington State’s special conceit.

Fresh out of the Marines and armed with the G.I. Bill, he enrolled at Wazzu in 1950 intending to study political and police science and probably head back into the Corps. Then he met Turi Ann Johnson “under the willow trees of the old golf course,” which her parents owned, and fell in love with her – about the same time he fell in love with broadcasting. A professor named Bert Harrison helped steer him into the booth, and in 1952 he called the Stanford-WSU game for KWSC radio – launching a 54-year career.

After graduation, he landed with KOMO in Seattle and it was there that he became the first to broadcast a sports event from the Soviet Union – a University of Washington crew race.

In fact, Jackson’s long association with college football masked a diversified portfolio – from local news anchor to covering Barry Goldwater’s nomination at the Republican National Convention with Walter Cronkite to an array of sports assignments.

He was the original play-by-play man on Monday Night Football, until Roone Arledge’s love affair with Frank Gifford was requited – a transition which, even if handled badly, at least spared Jackson the indignity of further fencing with Howard Cosell. He called MLB playoffs, the NBA, the Olympics and even the old “Superstars,” the original trashsport.

But his métier was college football and his postings all the game’s citadels – Tuscaloosa, South Bend, State College, Lincoln.

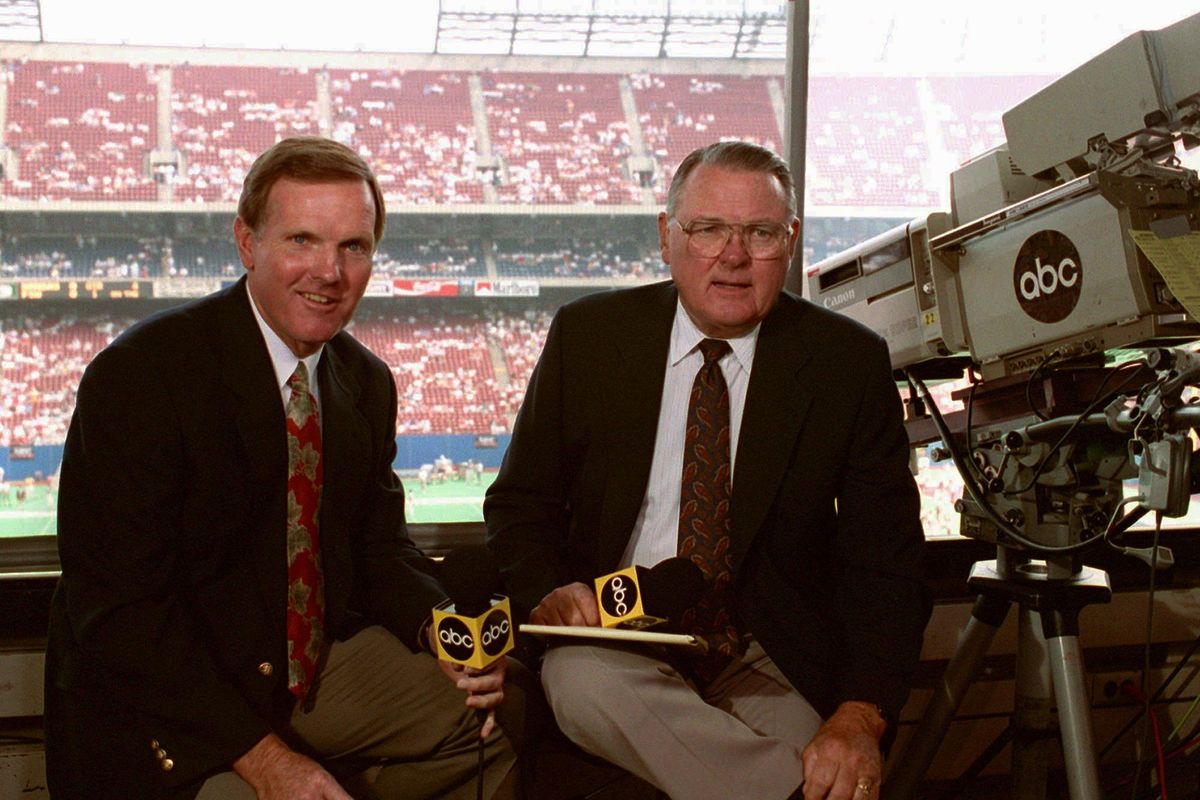

Just never Pullman, until 1997. After 30 years of doing network games for ABC, Jackson was finally back on campus for the season opener against UCLA – the game that jump-started the Cougars’ march to their first Rose Bowl in 67 years. Jackson, naturally, was there to call that, too, with Bob Griese, whose son Brian quarterbacked Michigan to a 21-16 victory.

But his heart was never far from Pullman. He rallied donors to build the alumni center, he was given the school’s Distinguished Alumnus Award, spoke at commencement and in time the campus broadcast center was named Keith Jackson Hall in his honor.

“My kind of place,” he called Pullman and the WSU campus, “with my kind of people.”

He shot straight with his kind of people. He was withering in his analysis of college football’s endless money suck – at his alma mater, too – and warned of “all kinds of cracks and crevices” threatening to swallow up the sport.

He retired, he said, because he “didn’t want to die in an airport parking lot,” but you also got the feeling he didn’t want to be just another voice on a Saturday slate that stretches from 9 a.m. to midnight, or later.

But when he donned the headset, he stepped off the pulpit. Then he was just a pro – OK, the pro – with cornbread touches. Coaches hitchin’ up their britches. Linebackers laying on good licks. Linemen who were lucky enough to get an in-person audience lit up when he called them “big uglies.”

Oddly, his signature line was quoted far more often than Jackson ever used it – and we never got clarification if it was “Whoa, Nelly!” or “Whoa, Nellie!” Fact is, it didn’t matter.

If you were reading it instead of hearing it out of Keith Jackson’s mouth, you were missing out on all the fun.