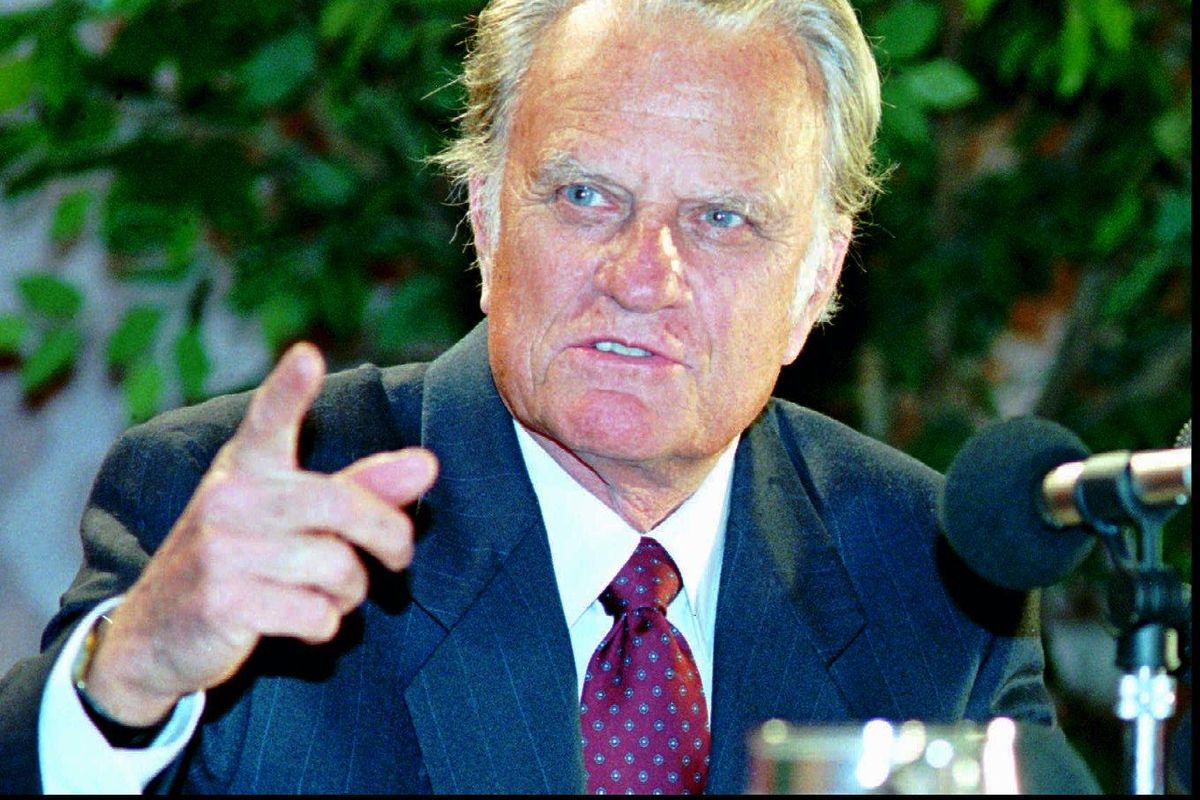

Billy Graham, minister to presidents and millions worldwide, dies at 99

When a young religious crusader named Billy Graham began preaching to the masses after World War II, he wore bright gabardine suits with loud, wide ties and argyle socks to show that Christianity wasn’t dreary.

And he did not hide behind a pulpit. He “stalked and sometimes almost ran from one end of the platform to the other,” one biographer noted, while beseeching unbelievers to give themselves to the higher power he praised with unassailable conviction.

That style drew 350,000 people to a tent in downtown Los Angeles over eight weeks in 1949 – the first major Billy Graham crusade. When it closed 65 sermons later, the mesmerizing preacher was known across the country – and, before long, around the world.

Graham, the most dominant American pastor of the second half of the 20th century, who lifted evangelism into the religious mainstream and through the power of his voice and personality united the often fractious worldwide evangelical community, died at his home Wednesday morning in North Carolina, the Associated Press confirmed. He was 99.

A Southern Baptist minister known for his simple faith and folksy charm, Graham had been in failing health over the last decade with Parkinson’s disease, prostate cancer and macular degeneration. He had been hospitalized numerous times with respiratory problems.

“No one was more important in legitimizing evangelism,” said William Martin, one of Graham’s biographers. “It’s now on equal footing to mainline Protestantism and Catholicism in the U.S.”

Graham’s reach was staggering. He preached to nearly 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories, according to figures compiled by the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, and was heard and seen by hundreds of millions more through television and radio, newspaper columns and the Internet. Graham wrote more than two dozen books, including a 1997 bestselling autobiography, “Just As I Am.” He counseled nearly every American president since Harry Truman, most recently meeting and praying with Barack Obama.

Before the Cold War ended, he talked his way behind the Iron Curtain to preach to millions throughout the communist world.

“From an almost hardscrabble early life in North Carolina, the precincts of small Bible colleges and Los Angeles tent revivals, he has come to be, with the pope, one of the two best-known figures in the Christian world,” said Martin E. Marty, a Lutheran pastor and divinity scholar.

More than 70 million copies of his sermons have been distributed worldwide. At the height of his career, he received an average of 10,000 letters a day and 8,500 written requests for speaking engagements a year. Most important to Graham, his staff estimated that during his public appearances about 3 million people responded to his call to “accept Jesus Christ as your personal savior.”

A registered Democrat who often seemed more comfortable in the moderate Republican camp, Graham knew 12 presidents and, in his prime, was a fixture at the White House. He spent the last weekend of the Lyndon Johnson presidency there and was the first overnight guest of Richard Nixon after he was sworn into office.

Graham attended or participated in eight presidential inaugurations, but he was also present at the White House during darker days of controversy and scandal. He stayed close to Johnson when the president’s popularity plummeted during the Vietnam War, and during Watergate publicly supported his longtime friend Nixon far longer than many thought prudent. During the Monica Lewinsky scandal, he quickly and publicly forgave President Clinton and privately counseled Clinton’s wife, Hillary, to forgive him as well.

Also close to Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Graham was one of the few people allowed to visit the former president in California after Reagan’s descent into Alzheimer’s disease. He also developed a close relationship with the Bush family, participating in the family’s annual summer retreats in Kennebunkport, Maine, starting when George H.W. Bush was vice president. It was there during meetings with Graham that George W. Bush, the president’s eldest son, started to turn his life toward Christianity.

Graham’s relationships with those in the Oval Office often helped him spread his message around the world in places such as South Africa, where he held integrated rallies, in the Soviet Union and in isolated North Korea, as Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy noted in their 2007 book, “The Preacher and the Presidents: Billy Graham in the White House.”

“If I had not been a friend of the presidents,” Graham told Gibbs and Duffy, “in most of those places, they wouldn’t have invited me to see them. The reason (Boris) Yeltsin invited me (to Russia in 1992) was because he knew I knew the president.”

The man, his audiences and his methods evolved since the early days of evangelical crusades, when tents, sawdust and financial “love offerings” were the trademarks.

His early preaching style was so physically charged – biographer Martin described it as “assault” – that the unconverted could not avoid paying attention. “He never faltered, never groped for a word, never showed the slightest doubt that what he said was absolutely true,” Martin said.

In later years, Graham toned down his wardrobe and refined his preaching. But the message remained much the same: that because people are innately sinful, they have been separated from God. Yet because Christ died for mankind’s sins, they can be forgiven and united with God if they repent and receive Christ as their savior.

Graham was “a heater-up of cooled-off Christians, a morale-builder to the already converted,” historian Marty said.

Graham began his rise with the 1949 tent revival in Los Angeles, which he called “a city of wickedness and sin.” Over two months, about 350,000 people sat on folding chairs in the “Canvas Cathedral” set up nightly at Washington Boulevard and Hill Street.

Southern California would later become the scene for four more record-shattering crusades, including a three-week series in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in 1963. On the final afternoon, 135,254 people clicked through the turnstiles to hear Graham preach.

Marshall Frady, in his book “Billy Graham: A Parable of American Righteousness,” described Graham as a man of “absolute, indestructible innocence.”

That innocence would prove problematic, particularly in his relationship with Nixon.

Graham, who became friends with Vice President Nixon during the Eisenhower presidency, crossed the line separating politics and religion in 1960, when he wrote an article for Life magazine endorsing Nixon over John F. Kennedy in their race for president. But Henry Luce, chief executive of Time-Life, had second thoughts about running the piece, and it was pulled at the last minute, much to Graham’s relief.

After Nixon’s election in 1968, Graham grew closer to his longtime friend, and that closeness would bring him considerable embarrassment in 2002, when tapes of a White House meeting from 1972 were released.

On the tapes, Graham was heard agreeing with Nixon that the American media were dominated by left-wing Jews. And then Graham, in his familiar North Carolina twang, went further:

“Not all the Jews, but a lot of the Jews, are great friends of mine; they swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I’m friendly with Israel. But they don’t know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country.”

The remarks shocked Graham supporters and Jewish leaders because the preacher was seen as a staunch ally of the Jewish people. In addition to his unflagging support of Israel, Graham also protested the treatment of Soviet Jews and chastised his fellow Southern Baptists for singling out Jews for conversion.

When the tapes surfaced, Graham initially issued a short apology, saying that he didn’t remember making the comments. When the controversy continued, Graham issued another statement: “I don’t ever recall having those feelings about any group, especially the Jews, and I certainly do not have them now. My remarks did not reflect my love for the Jewish people. I humbly ask the Jewish community to reflect on my actions on behalf of Jews over the years that contradict my words in the Oval Office that day.”

After Nixon’s resignation in the Watergate scandal, Graham kept a discreet distance from Washington, although he conducted the funeral of Nixon’s wife, Pat, in 1993 and the former president’s funeral in Yorba Linda in 1994.

Though Graham’s closest relationship with a president was thought to be with Nixon, he insisted he was actually closer to Johnson, noting that he was at the Johnson White House 27 times but only three times at Nixon’s. He also presided at Johnson’s funeral in 1973.

Graham and Johnson also shared a commitment to civil rights. In 1953, at a crusade in Chattanooga, Tenn., Graham told volunteer ushers that blacks were to sit wherever they pleased, that there was no segregation at the foot of Jesus’ cross. Segregated seating was never allowed at subsequent crusades, even in South Africa during apartheid.

Late in life, Graham reflected on his involvement in politics during a January 2011 email interview with Christianity Today magazine. Asked what he would do differently if he could, Graham replied: “I would have steered clear of politics. . People in power have spiritual and personal needs like everyone else, and often they have no one to talk to. But looking back, I know I sometimes crossed the line, and I wouldn’t do that now.”

Ironically, given the later controversy over his 1972 statements, Graham’s friendship with Jews as well as Catholics and liberal Protestants alienated many right-wing fundamentalists in the 1950s and ‘60s. In the 1980s, he distanced himself from the conservative right by speaking out in favor of such issues as nuclear disarmament.

Graham’s drift toward liberalism occasionally put a dent in his popularity among his more conservative supporters. One of his biggest public relations challenges came after a preaching trip to the Soviet Union in 1982. Graham returned home to defend himself against a flurry of accusations that he had gone naively soft on communism when he stated that he saw no religious persecution during his six-day trip.

He insisted he was not “duped” and said that behind the scenes, he spoke out forcefully, though “with a smile on my face,” against religious repression and human rights violations in the Soviet Union.

Through all his travels, Graham insisted that the Bible was his simple credo of faith.

Ordained in 1939, Graham was never seriously threatened by the ethical and moral troubles that plagued many high-profile evangelists. He set up a system of checks and balances, including an independent board of directors for the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, to establish his salary and housing allowance, which was believed to have been well under $150,000. He also never spent time alone – even for lunch or a ride to the airport – with a woman other than his wife.

Frugality and humility were byproducts of Graham’s childhood, spent on his family’s dairy farm near Charlotte, N.C. One of four children born to Morrow Coffey and William Franklin Graham, Billy Frank, as he was known to his family, was born Nov. 7, 1918, and grew up milking Holsteins and working in the fields.

At 16, Graham attended several nights of a tent revival that passed through town, stepping forward one evening when the fire-and-brimstone traveling evangelist asked if anyone wanted to give his life to Jesus Christ.

“That night I committed myself unreservedly to Jesus Christ,” he recalled. “I burned all my bridges behind me. I determined to spend the rest of my life in his service.”

He went to the Florida Bible Institute, now known as Trinity College, in Dunedin, Fla. The year before his graduation in 1940, Graham was ordained a Southern Baptist preacher in a small, white clapboard church near Palatka, Fla. In the fall of 1940, Graham enrolled at evangelical Wheaton College in Illinois, where he met Ruth McCue Bell. They both graduated in 1943, the same year they married, and settled near Montreat, N.C.

Graham began his first formal preaching job as the pastor of a church in Western Springs, Ill., then became a barnstorming speaker for the new Youth for Christ movement that swept the country during the 1940s. In 1947, Graham became president of Northwestern College and Seminary, a small school in Minneapolis, the city that three years later was to become the headquarters for his Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

The year 1949 proved to be a turning point. That August, Graham was greatly troubled about whether the Bible was fully true. While attending a student conference at Forest Home, a Christian conference center in the San Bernardino Mountains, he went into the woods alone. There, he prayed, “Lord, I accept the Bible by faith as your word.”

Relating the incident to the Los Angeles Times 25 years later, Graham said, “I couldn’t prove everything or logically defend it, but from that moment on, I have never had a serious problem about the Bible’s authority.” Graham believed there was a significant connection between that decision and the unprecedented success of his Los Angeles tent crusade the next month.

More skeptical voices attributed his success to the support of publisher William Randolph Hearst, who ordered his newspapers to print extensive stories about the young “revivalist.”

The 1949 crusade in Los Angeles was almost a disaster. Some planning committee members feared that the 6,000-seat tent would be too big, since the 30-year-old Graham was relatively unknown on the West Coast. But the scheduled three-week crusade was extended to eight weeks. Among the converted was Stuart Hamblen, a cowboy singer, gambler and racehorse owner who used his popular radio show to tell how he had found God at Graham’s tent revival.

The front-page attention in Hearst’s newspapers quickly rippled around the world as other papers picked up the story. Celebrities, including Gene Autry and Jane Russell, attended, and some walked the sawdust aisle of the tent to renounce sin and embrace Christian faith, among them Western stars Roy Rogers and Dale Evans.

Within months, Life, Time and Newsweek magazines all devoted major features to “the new Billy Sunday,” a reference to the popular evangelist of the early 20th century.

As mass evangelism gained new respect, Graham’s name became a household word in the United States and abroad. In 1954, his 12-week London crusade brought him international attention. In the decades that followed, record throngs in the world’s principal cities responded to the Graham team’s well-organized and widely publicized meetings: 2.3 million in New York, 2.6 million in Glasgow, Scotland, and 3.2 million in South Korea, including 1 million at a single meeting in Seoul.

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, now based in Charlotte, grew into a powerful worldwide conglomerate that included a radio program, a film production unit, a newspaper column, magazines and television programs.

Graham received numerous awards during his lifetime, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian decoration, and the Congressional Gold Medal.

Graham’s wife, Ruth, died in 2007. He is survived by his son William Franklin Graham III, known as Franklin, who took over the Billy Graham Evangelistic Assn. in 2001; another son, Nelson Edman “Ned” Graham; three daughters, Virginia “Gigi” Graham Foreman, Anne Graham Lotz and Ruth Bell; 19 grandchildren and numerous great-grandchildren; and a sister, Jean Ford.

Some years ago, Graham told an L.A. Times reporter that he was “looking forward to heaven” and wanted to be remembered “as a man of integrity.”

Why, he was asked, did so many hundreds of thousands flock to hear him wherever he went?

“Well,” the evangelist replied, pausing for a moment, “part of the answer, I suppose, is I’ve been preaching so long, and curiosity. But I prefer to think that it’s God.”

“Why did God choose you?” he was asked.

“That’s the first question I’m going to ask him,” Graham replied.